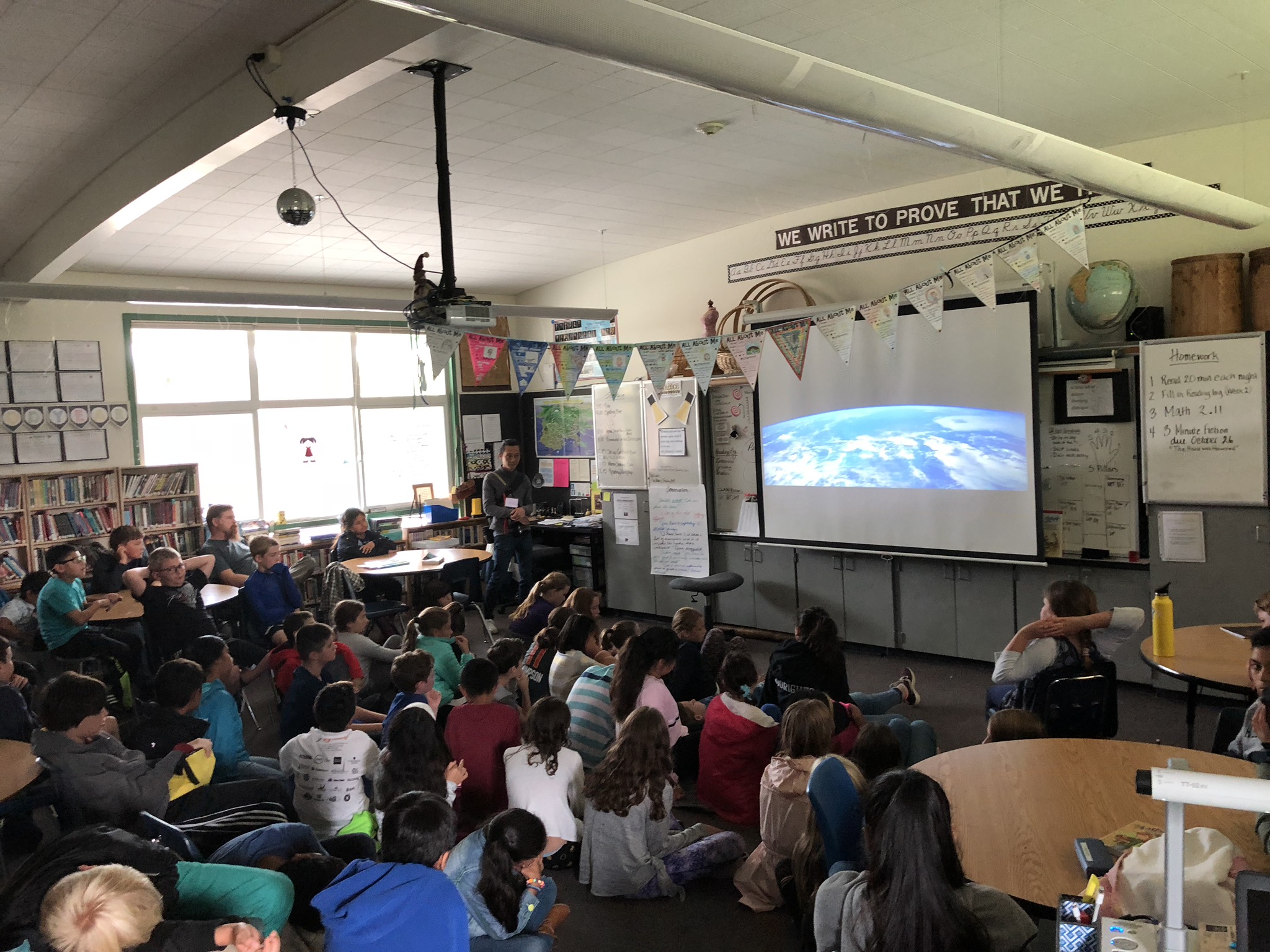

Artwork created by a group of 4th graders at PS 148 in Queens

“If we want our children to grow up learning how to learn and how to think, we should be working in the other direction: make the classroom look more like the art studio.” – Christopher Wisniewski

Forty-one years ago, Agnes Gund read an article about the arts being virtually eliminated from the budget of the NYC Board of Education. She had an idea. What about bringing visual artists to teach in schools where there was no art instruction? Studio in a School, the organization she founded, has done just that. The program has grown from three to two hundred schools throughout New York City, and is now planning to scale nationally.

Studio works in partnership with the public school system, rather than in opposition to it. 30,000 students a year currently benefit from the service. Executive Director Chris Wisniewski explains that flexibility has been the secret to growth. For example, when New York City launched Universal Pre-K, Studio was able to offer professional development programs to the influx of new early childhood teachers. What makes Studio so special? Wisniewski says he did his own research when he started there a little over two years ago and got the same answer from everyone: “Our Artist Instructors.”

The Global Search for Education welcomes Christopher Wisniewski to talk about artists coming to a school near you.

© Mindy Best

“In general, we should be focusing on making middle school education better—not simply more successful in promoting student achievement but also more learner-centered, more creative, more project-based.” – Christopher Wisniewski

Shifting skills in a changing world. There’s a big emphasis on creativity in curriculum today at a time when public school art education budgets are being cut. How does arts education and visual intelligence prepare youth for a changing world, and how can visual intelligence permeate other academic subjects and improve creativity generally?

I love this question—it’s related to our reason for using artists as teachers. Authentic art making experiences provide opportunities for self-expression, and also help to teach ways of thinking – an “artist’s habits of mind.” These are metacognitive skills that are closely aligned to the 21st century skills educators across a broad spectrum of disciplines are placing increasing emphasis on. Through art making—particularly, I feel, with an artist as teacher—students iterate, envision, persist, collaborate, and innovate.

The teaching and learning I see happening in our art studios is learner-centered and project-based. There is also often a lower barrier to entry in the art studio than in other classrooms. For students with different learning needs and English language learners, for example, a visual art making experience can provide an opportunity to connect, engage, and interact that is otherwise rare during the school day. This is one reason why there is so much power in integrating authentic art experiences into “academic subjects.”

It is certainly possible to have an art making experience that is not creative or learner-centered. I do not see any value in asking a student to copy Starry Night, though it happens in art classes all the time. That kind of lesson treats the art classroom like an “academic” classroom. If we want our children to grow up learning how to learn and how to think, we should be working in the other direction: make the classroom look more like the art studio.

How do you build deep, meaningful partnerships with schools, principals, teachers, and families? How does Studio in a School empower students and real-world artists at the same time?

This is easy to answer, but difficult to achieve. We approach every partnership individually and begin every program with a conversation involving the principals, classroom teachers, and our Artist Instructors. Everyone sitting at the table understands that each stakeholder brings different expertise to the conversation and that everyone needs to be heard. The principal and the classroom teachers understand their students, their needs, the community they are serving, and their instructional goals. We understand visual art. We ask our Artist Instructors to bring their creativity to the planning process.

The keys are to listen to your partners and set clear expectations up front.

© Mindy Best

“Nothing replaces the exploration of materials and the experience of physically transforming a piece of paper with paint or scissors or of manipulating clay.” – Christopher Wisniewski

What are the differences between being taught by an artist versus an art teacher? How do the artists and the teachers work together in your programs?

I have great respect for art teachers and for artists. Our students get excited about having instructors who are exhibiting artists. We encourage our Artist Instructors to share their own work with their students and to let their students know when they have exhibitions. In a city like New York, it opens the students up to the idea that artists and art are all around them—not just at premier museums but in galleries, restaurants, libraries, parks, subway stations, and other public spaces.

Very few of our Artist Instructors come to us with formal training in education, though most have some teaching experience. We put them through months of training on pedagogy, child development, classroom management, curriculum, and more before they lead a class. Studio’s success has hinged on a reputation for quality. We have achieved that by hiring extraordinary artists who work with us to become great teachers. And when they are in schools, they always collaborate with the classroom teachers.

You mentioned that a lot of the art learning is focused on the lower grades – why is that? Why aren’t there more middle and high school programs?

We have a “long tail” into middle and high school. One reason for that is practical: in New York City, middle and high school students are not with the same classroom teacher all day. That makes scheduling difficult.

But art education is a more specialized offering for older students. Some teenagers want to study art through high school; some have other interests. I believe that every five year-old should have an experience painting at school. That is less true of a fifteen year old, though they should have access to art if they want it.

We do know, however, that middle school is a critical inflection point in a young person’s education. In general, we should be focusing on making middle school education better—not simply more successful in promoting student achievement (though that is the goal) but also more learner-centered, more creative, more project-based. Art education supports those values, so it stands to reason that we should have middle schools that are more art-rich.

Artwork created by a 3rd grader at Sheridan Academy for Young Leaders in the Bronx

“I would like Studio to integrate technology into our programs for older students, keeping art and art making at the center of what we do.” – Christopher Wisniewski

How is the development of tech changing and reshaping art education? How do you use tech to enhance arts education?

Our curriculum is grounded in traditional studio art media. In the early grades, I never see that changing. For young learners, nothing replaces the exploration of materials and the experience of physically transforming a piece of paper with paint or scissors or of manipulating clay. These are moments of discovery, expression, and agency.

For older students, the story is different. Many of our Artist Instructors integrate technology into their own work, which is an opportunity for us. The challenge with STEAM programs is that they often involve a bait-and-switch: you get the students interested by promising them they’ll make, for example, a video game, but you are actually teaching them how to code, which is hard. The learning experience can be frustrating, because the student and the teacher have different goals. I would like Studio to integrate technology into our programs for older students, keeping art and art making at the center of what we do. The technology becomes another tool to support the creative process rather than the focus.

How are you planning to expand Studio in a School? What are the challenges?

Studio’s New York City Schools Program already operates at scale. Our challenge locally is to maintain quality while remaining responsive and adaptive.

Nationally or globally, I envision something that is replicable, though not, in a narrow sense, scalable. The Studio Institute is less interested in franchising than in sharing our approach with other communities. This goes back to what makes Studio successful in New York: authentic partnerships amongst school leaders, classroom teachers, and artists informed by Studio’s philosophy and commitment to quality. This “recipe” has transformed school communities in every corner of the city. I see no reason why our approach wouldn’t replicate in other cities or countries or disciplines.

C M Rubin and Christopher Wisniewski

Join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. MadhavChavan (India), Charles Fadel (U.S.), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. EijaKauppinen (Finland), State Secretary TapioKosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Geoff Masters (Australia), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (LyceeFrancais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today.

The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, includingThe Real Alice in Wonderland, is the publisher of CMRubinWorld and is a Disruptor Foundation Fellow.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments