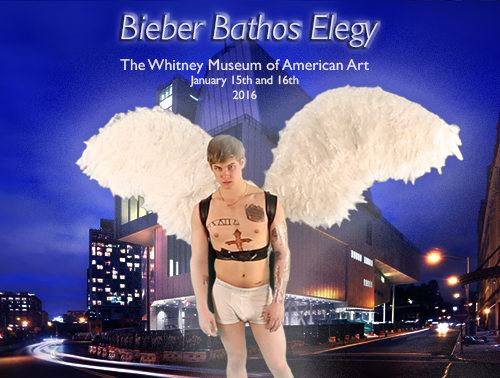

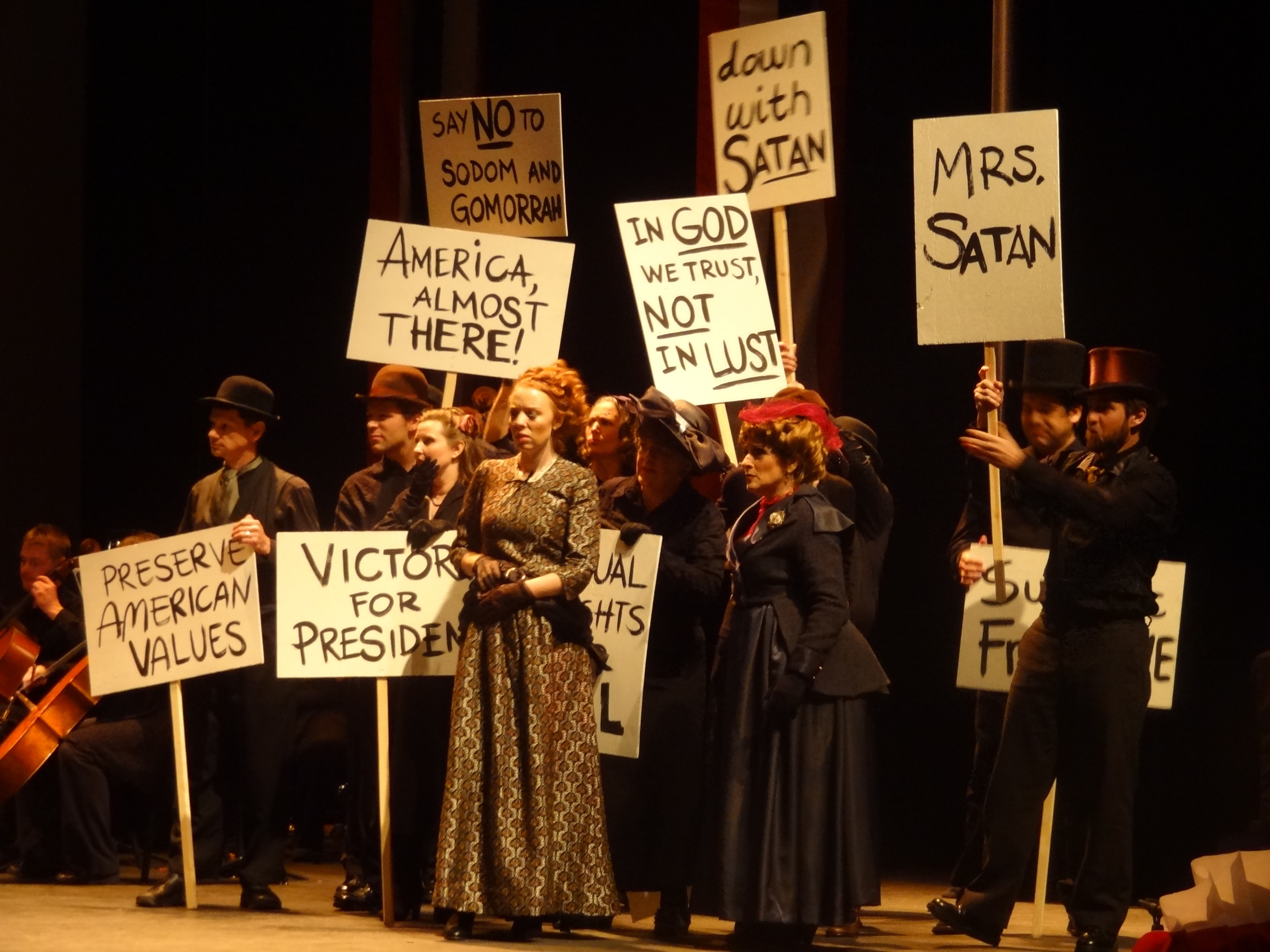

“It’s time for me to grow up,” Justin Bieber said in a recent interview. And growing up amidst the pressures of a complex world and a relentless public eye is the tricky, tenuous, entertaining theme of New York based artist Felix Bernstein’s new musical spectacle, Bieber Bathos Elegy, which will debut at The Whitney Museum of American Art this month. During the performance, Bieber visits the stage as a prophetic angel to critique and parody the show inspired by events from Bernstein’s life and critically acclaimed writings, collected recently in Burn Book (Nightboat). This hybrid work of opera, poesia, cabaret drag (artist Shelley Hirsch leads a gay youth’s chorus in a rendition of “Tomorrow” from Annie) and deconstructive criticism features Bernstein as the thinking millenial’s poet trying to figure out where lieth the reality in the labyrinth of life.

Bernstein is the author of Note sulla poesia post-concettuale e Burn Book. Bernstein’s writings have appeared in BOMB, Hyperallergic, and Poetry Magazine among others. In my interview with Felix that follows, he discusses Bieber as icon, the meaning of Bathos and how a devastating personal tragedy gives his path purpose.

Why Justin Bieber? Is he someone you are drawn to as an artist?

Not usually, except as a muse of sorts. In his new album, he’s trying to reach his ex, selena Gomez, but failing to. That’s typical of a pop album, but what got me was this interesting aesthetic maturity that comes when he realizes it’s not all about reaching her, or saying you are sorry, or being in pain. There is also a formal complexity, a craft, that’s for himself, not just for his fans, and not just for revenge.

I started making videos in high school and there is a lot of awkwardness about that now, as people either like me for that stuff, or dislike me for that stuff, or see me as childish, or not a serious artist, or a brat. But either way, it’s an image of myself that I can’t control, that I feel split off from, and yet I can’t cut off, like Bieber’s pressure to mature and to divorce himself from prior images, but also his addiction to the “hotness” of his self-image.

Come ha fatto Bieber Bathos Elegy at The Whitney come about? What can the audience expect?

At the old Whitney, I performed for the artist’s band Red Krayola, and for the multimedia artist, Andrew Lampert. The new Whitney museum has a really awesome theater, and I was asked to think of something to do there. And they also have a performance curator, Jay Sanders, which is a fairly new thing for a museum to have. I used my background in poetry, criticism and music to create something that would be right for a theater. I wrote a libretto that mixed lots of personal stuff about my life, with fantasies of Justin Bieber, and musical spectacle, which became part of my book of poems, Burn Book. But I also show my thought process of how I get to the things I do, rather than it just being about theatrical spectacle.

In the show, I get to work with two visionary artists – the visual artist Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, as well as the experimental vocalist Shelley Hirsch, both of whom are very influential to me. Thomas is a Stonewall veteran and has been in the city since then, so has a very interesting take on the way that gay art has transformed into what it is now, which we both agree, is far from visionary.

Bathos?

An extreme display of sadness that seems ridiculous or funny.

Who are some non-poets that directly influence your poetry? How do they inspire you?

I listen when I’m writing poetry to 30-second clips of songs that I repeat for hours, which inspire me to keep writing and writing. I listen to Dusty Springfield, Sweeny Todd, Cocteau Twins, Fiona Apple – I’ll pick a particularly resonant emotional crux of the songs to repeat, but it is not simply the emotion but the repetition that is crucial. If you simply confess how you feel in a given moment, you are sad and hurt, in a very transparent and generic way, but it fails to be moving. But to hear the repetition of phrases, you start to really see the formal constraints, the rigor, and the practice of the singer. If you’re able to represent how you feel in different ways, with differing objective correlatives (as T.S. Eliot put it), then in interesting ways you can maybe start to reach people. In a culture where there is so much confession, so many people trying to reach each other through sharing their feelings, like the Adele song “Ciao,” it maxes out. It becomes a joke. Eliot is important to think of here, because the song “Memoria,” da Cats, is based on his words but also based on the words of Robert Lowell, which are really important to my show and the book. One of the best things that Lowell wrote, at the end of his life, era “sometimes everything I write / with the threadbare art of my eye / seems a snapshot, / lurid, veloce, garish, grouped, / heightened from life, / yet paralyzed by fact.” I don’t want to be paralyzed by fact. But sometimes, naturalmente, sono.

Are there any ideas or themes that recur throughout your work?

A recurrent theme is ugliness and annoying people. When I was making videos in high school, I was motivated by an attempt to annoy people, who had certain expectations around the process of “coming out of the closet,” and how one is supposed to perform being gay or being a serious artist. So I used a clown, childlike persona to annoy people who wanted me to be sad and serious. But when I left Bard College, and moved back to New York City, the expectation changed; it was for me to social network, and be very cosmopolitan and hip, to use academic jargon, and make work like everyone else, join a clique, e così via. I tried to make fun of that glamour and to critique the scenes that surrounded me. And take on a humorous distance from my own life, amici, and family. So I lost some friends, and made some friends. In my new show, I try to “annoy” those coming in with an expectation of fashionable, ironic pop art that will reference hot museum topics and make the in-crowd feel safe.

Both your parents are successful artists. How has that affected you?

It’s impacted people’s judgments of me but it also gives an interesting perspective on lineage, intergenerational politics, and the ways that artists are canonized and judged at different points in their lives. And the way a child feels and thinks and is judged is something I return to all the time.

What is the importance of Elegy to the show?

In mid-December 2008, my sister, Emma Bee Bernstein, took her life, all'età di 23. And the book and show are happening in coincidence with my being 23 during this anniversary. Time is senseless, and this show and book serves as a dirge to remember her. But it’s also about the many variations on how to formally depict loss: pathos, bathos, humor, restraint, or opera? Ancora, all of this mourning is encased in a glass snowglobe. There’s frustrating propulsion to move on. In your early twenties, you have to go really fast otherwise you miss the boat. And I’m on the boat…but I’m not willing to merely look forward.

(All photos are courtesy of Luke Smithers)

Per ulteriori informazioni sulle Bieber Bathos Elegy at The Whitney

Unitevi a me e leader di pensiero di fama mondiale tra cui Sir Michael Barber (Regno Unito), Dr. Michael Block (Stati Uniti), Dr. Leon Botstein (Stati Uniti), Il professor Argilla Christensen (Stati Uniti), Dr. Linda di Darling-Hammond (Stati Uniti), Dr. MadhavChavan (India), Il professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Il professor Howard Gardner (Stati Uniti), Il professor Andy Hargreaves (Stati Uniti), Il professor Yvonne Hellman (Paesi Bassi), Il professor Kristin Helstad (Norvegia), Jean Hendrickson (Stati Uniti), Il professor Rose Hipkins (Nuova Zelanda), Il professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Onorevole Jeff Johnson (Canada), Sig.ra. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgio), Dr. EijaKauppinen (Finlandia), Sottosegretario di Stato TapioKosunen (Finlandia), Il professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgio), Il professor Hugh Lauder (Regno Unito), Signore Ken Macdonald (Regno Unito), Il professor Geoff Masters (Australia), Il professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Il professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. PAK NG (Singapore), Dr. Denise Papa (Stati Uniti), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (Stati Uniti), Richard Wilson Riley (Stati Uniti), Sir Ken Robinson (Regno Unito), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finlandia), Il professor Manabu Sato (Giappone), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OCSE), Dr. Anthony Seldon (Regno Unito), Dr. David Shaffer (Stati Uniti), Dr. Kirsten Immersive Are (Norvegia), Cancelliere Stephen Spahn (Stati Uniti), Yves Theze (LyceeFrancais Stati Uniti), Il professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Il professor Tony Wagner (Stati Uniti), Sir David Watson (Regno Unito), Professor Dylan Wiliam (Regno Unito), Dr. Mark Wormald (Regno Unito), Il professor Theo Wubbels (Paesi Bassi), Il professor Michael Young (Regno Unito), e il professor Zhang Minxuan (Porcellana) mentre esplorano le grandi questioni educative immagine che tutte le nazioni devono affrontare oggi.

Il Global Ricerca per l'Educazione della Comunità Pagina

C. M. Rubin è l'autore di due ampiamente lettura serie on-line per il quale ha ricevuto una 2011 Premio Upton Sinclair, “Il Global Ricerca per l'Educazione” e “Come faremo a Leggere?” Lei è anche l'autore di tre libri bestseller, Compreso The Real Alice in Wonderland, è l'editore di CMRubinWorld, ed è un disgregatore Foundation Fellow.

Segui C. M. Rubin su Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Commenti recenti