“Although in the U.S. there are increasing conversations about personalized learning, digital learning, deeper learning and alike, the prevalent content delivery mechanism in most schools remains the traditional, 20th century approach to learning. The tutorial networks give us an opportunity to start the conversation about what strategies engage students in the process of learning.” – Helen Janc Malone

What happens when you place the child back at the heart of learning?

This simple philosophy was used to launch an experiment with the goal of improving eight poor rural Mexican public schools. Da quando 2009, the tutorial networks (as the grassroots initiative was called) have been leading a country-wide school improvement effort in 9000 schools with the lowest academic achievement on the national standard test. Oggi in parte 4 di “Istruzione è un mio diritto,” we will explore what education reformers can learn from this unique and innovative strategy which has attained such positive results that it is now being supported by educators and policymakers in Mexico’s highly centralized system of public school education.

It is my pleasure to welcome to The Global Search For Education, Gabriel House, the founder of Mexico City-based Convivencia Educativa (Educational Coexistence) A.C. and Redes de Tutoría S.C. (Mentoring Networks). I also asked Helen Janc Malone, author of Leading Educational Change: Problemi globali, Sfide, e lezioni sulla riforma Whole-System, which features Gabriel’s work, a pesare in. Helen è la direttrice dell'Institutional Advancement presso l'Institute for Educational Leadership di Washington, DC.

Advertisement

“Tutoring what one learns, and has shown to have mastered, becomes the occasion to learn in depth and to create a convivial community in the group.” – Gabriel House

Gabriel, please summarize the goals of the tutorial networks.

Tutorial networks in public schools are a means to obviate a major distortion imposed on learners by the predominant culture that determines the themes that teachers and students should learn, and the times within which they should be mastered. Instead of allowing the free encounter of interested learners with a competent mentor, standard practices in classrooms force impersonal recitations of content to generally passive audiences. The known effect is not only lack of interest in the particular subject being presented, but the missed opportunity to practice learning academic subjects in earnest, with commitment, visible results and satisfaction – the foundations of the enduring ability to learn by oneself. Contrary to common practice, tutorial relationships in a classroom facilitate the matching of what is of interest to each student with what is available in the mentor’s repertoire. The immediate objection, from the conventional perspective, is that it would be well-nigh impossible for one teacher to match the interest of every student in a large group, even if the teacher is knowledgeable and willing to help. Tutorial networks deflect the objection, as all members in the group learn from one another. Tutoring what one learns, and has shown to have mastered, becomes the occasion to learn in depth and to create a convivial community in the group.

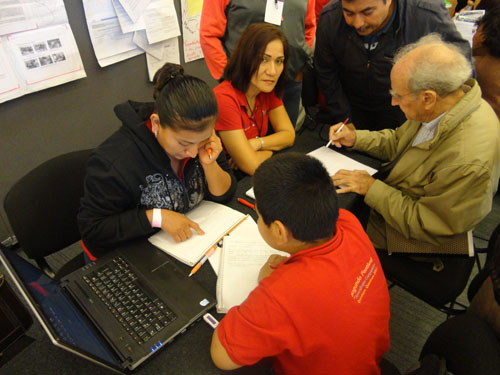

Tutorial networks were first started at the margins of a public school system, where chronic deficiencies in structure, transient teachers, and regional poverty were invitations to try radical innovations, without disturbing the rest of the schools. As regular classrooms turned into learning communities and students became capable of mentoring what they had mastered, opportunities to learn multiplied: students moved eagerly to neighboring schools to share what they knew with fellow students, and in turn, these students and their teachers created new learning communities. Poi, authorities changed from allowing a radical experiment in almost lost cases to promoting tutorial networks to improve learning in low performing, though better served schools. This way the transformation began to be seen as a large scale educational change.

Two major factors account for the transformation that already has touched thousands of public schools in Mexico: the acceptance of authorities in charge of the system, naturalmente, but most striking, the inner conversion of teachers and students from passive receptors of external directives to managers of their own learning and active agents of change in neighboring schools. The newly discovered power among ordinary teachers and students, not only to learn, but also to teach, ha dimostrato di essere la maggiore forza di sostenere e diffondere reti tutoriali nel sistema scolastico.

Come la competenza di base di prendere il controllo del proprio apprendimento di uno diventa pratica regolare tra un numero crescente di attori educativi, le possibilità di un aumento di servizio più professionale.

“Una volta che la competenza di controllare e condividere il proprio apprendimento diventa un link di base in una rete estesa di consulenti, insegnanti, studenti e anche le loro famiglie, le basi di una professione autonoma è disposto.” – Gabriel House

What have been the benefits and what have been the challenges?

The major benefit has accrued to teachers and students who perceive, as never before, the satisfaction of achieving visible, valuable learning. The obvious reason is the perfect match of interest and capacity that obtains in tutorial dialogues when tutor and tutee face a common challenge. Basic to the success also is the equity of the exchange predicated on mutual trust, truth and commitment. Such an exchange invariably leads to completion, sempre soddisfacente in un senso reale, mai differita di qualche futuro vago, e sempre aperta a ulteriori conquiste intellettuali. La prova di un buon apprendimento e la fruizione di eccellenza arrivano quando il tutee diventa un tutor per gli altri studenti, ai familiari e, a volte anche per gli insegnanti e gli amministratori vicini. Scambi tra gli studenti di diverse scuole, al fine di dare e ricevere tutoraggio diventare naturale, anche necessario dimostrare competenza, aumentare la conoscenza comune ed estendere la pratica.

Una volta che la competenza di controllare e condividere il proprio apprendimento diventa un link di base in una rete estesa di consulenti, insegnanti, studenti e anche le loro famiglie, the groundwork of an autonomous profession is laid out. Training, insegnamento, evaluating, managing school chores and administering resources are easily integrated and make possible the rendering of the quality service expected from a public school system.

The new relationships that started at the learning core create stronger social relationships within the school system, and in a very real sense democratize the institution, since the newly discovered power of every learner commands the process.

The challenge to the continuing expansion of tutorial networks, come sempre, is the ingrained habit of following tried patterns even if they do not deliver the promised results. It is the satisfactory experience of good results in face to face encounters that causes the inner conversion to learn in depth and enjoy sharing it.

“The fact that these networks have spread from dozens to thousands of schools in a manner of a few years and have been accepted by the educational establishment as a credible improvement approach, speaks to the power and evidence these tutorial structures have demonstrated to their communities and to the public at large. -Helen Janc Malone

Helen, what can we learn from this approach to school reform?

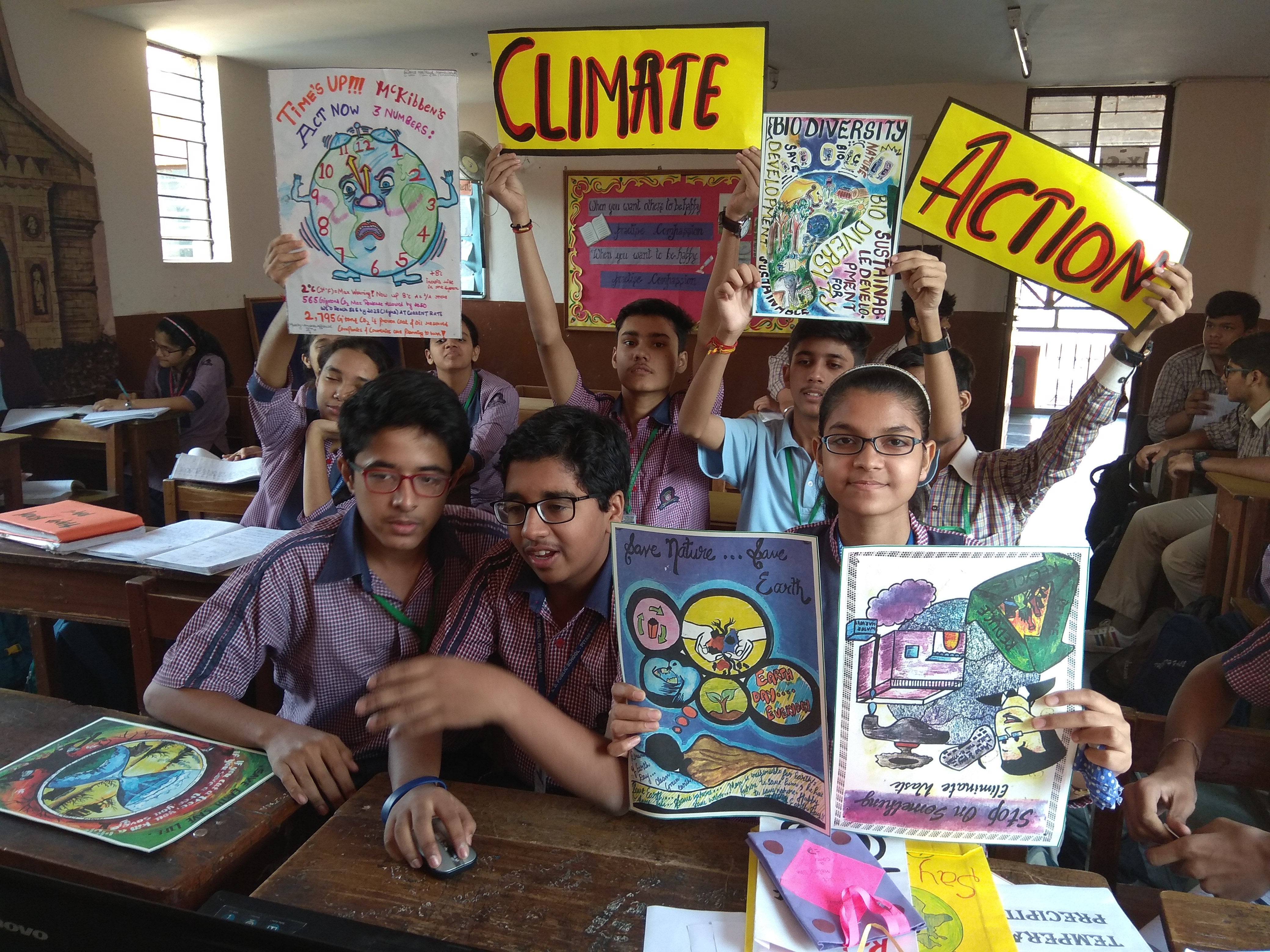

Tutorial networks in Mexico turn school reform on its head. As opposed to hoping educational change trickles down from national or regional policies and external pre-packaged reforms, tutorial networks create change from the grassroots level. The fact that these networks have spread from dozens to thousands of schools in a manner of a few years and have been accepted by the educational establishment as a credible improvement approach, speaks to the power and evidence these tutorial structures have demonstrated to their communities and to the public at large.

What is unique and innovative about the tutorial networks is that they put the learner and the process of learning at the center of the education endeavor, and focus on tutorial relationships as a driver for democratic, equitable learning environment, absent of traditional, grade-level, standardized, rigid structures that often disengage students. Taking agency for instructional delivery and ownership of learning is empowering and motivating for both the tutors and the tutees. There is a great sense of pride that comes from receiving personalized learning, mastering content and sharing that knowledge with peers. An added advantage of such a strategy has been the excitement that spreads beyond the school walls and spills out into the community, where families again begin to see schools as centers for learning and development. This is particularly evident where tutorial networks have been able to positively transform rural, high-poverty, low-performing schools.

Although in the U.S. there are increasing conversations about personalized learning, digital learning, deeper learning and alike, the prevalent content delivery mechanism in most schools remains the traditional, 20th century approach to learning. The tutorial networks give us an opportunity to start the conversation about what strategies engage students in the process of learning.

Helen Janc Malone, C.M. Rubin, Gabriel House

All Photos are courtesy of Jessica Trujano.

For more information see Leading Educational Change: Problemi globali, Sfide, e lezioni sulla riforma Whole-System (Teachers College Press, 2013): http://store.tcpress.com/0807754730.shtml

Nel Global Search per l'Educazione, unirsi a me e leader di pensiero di fama mondiale tra cui Sir Michael Barber (Regno Unito), Dr. Michael Block (Stati Uniti), Dr. Leon Botstein (Stati Uniti), Il professor Argilla Christensen (Stati Uniti), Dr. Linda di Darling-Hammond (Stati Uniti), Dr. Madhav Chavan (India), Il professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Il professor Howard Gardner (Stati Uniti), Il professor Andy Hargreaves (Stati Uniti), Il professor Yvonne Hellman (Paesi Bassi), Il professor Kristin Helstad (Norvegia), Jean Hendrickson (Stati Uniti), Il professor Rose Hipkins (Nuova Zelanda), Il professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Onorevole Jeff Johnson (Canada), Sig.ra. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgio), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finlandia), Segretario di Stato Tapio Kosunen (Finlandia), Il professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgio), Il professor Hugh Lauder (Regno Unito), Il professor Ben Levin (Canada), Signore Ken Macdonald (Regno Unito), Il professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Il professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. PAK NG (Singapore), Dr. Denise Papa (Stati Uniti), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (Stati Uniti), Richard Wilson Riley (Stati Uniti), Sir Ken Robinson (Regno Unito), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finlandia), Il professor Manabu Sato (Giappone), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OCSE), Dr. Anthony Seldon (Regno Unito), Dr. David Shaffer (Stati Uniti), Dr. Kirsten Immersive Are (Norvegia), Cancelliere Stephen Spahn (Stati Uniti), Yves Theze (French Lycee Stati Uniti), Il professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Il professor Tony Wagner (Stati Uniti), Sir David Watson (Regno Unito), Professor Dylan Wiliam (Regno Unito), Dr. Mark Wormald (Regno Unito), Il professor Theo Wubbels (Paesi Bassi), Il professor Michael Young (Regno Unito), e il professor Zhang Minxuan (Porcellana) mentre esplorano le grandi questioni educative immagine che tutte le nazioni devono affrontare oggi.

Il Global Ricerca per l'Educazione della Comunità Pagina

C. M. Rubin è l'autore di due ampiamente lettura serie on-line per il quale ha ricevuto una 2011 Premio Upton Sinclair, “Il Global Ricerca per l'Educazione” e “Come faremo a Leggere?” Lei è anche l'autore di tre libri bestseller, Compreso The Real Alice in Wonderland.

Segui C. M. Rubin su Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Commenti recenti