“Embora na U.S. há cada vez mais conversas sobre a aprendizagem personalizada, de aprendizagem digital, aprendizado mais profundo e afins, o mecanismo de entrega de conteúdo predominante na maioria das escolas continua a ser o tradicional, 20abordagem século XIX para o aprendizado. As redes de tutoria nos dar a oportunidade de iniciar a conversa sobre o que estratégias envolver os alunos no processo de aprendizagem.” – Helen Janc Malone

O que acontece quando você coloca a criança de volta no centro da aprendizagem?

This simple philosophy was used to launch an experiment with the goal of improving eight poor rural Mexican public schools. Desde 2009, as redes tutorial (como a iniciativa popular foi chamado) têm levado um esforço de melhoria da escola em todo o país 9000 schools with the lowest academic achievement on the national standard test. Hoje na parte 4 de “Educação é meu direito,” we will explore what education reformers can learn from this unique and innovative strategy which has attained such positive results that it is now being supported by educators and policymakers in Mexico’s highly centralized system of public school education.

It is my pleasure to welcome to The Global Search For Education, Câmara de gabriel, the founder of Mexico City-based Convivencia Educativa (Educational Coexistence) A.C. and Redes de Tutoría S.C. (Mentoring Networks). I also asked Helen Janc Malone, author of Leading Educational Change: Questões Globais, Desafios, e Lições sobre a Reforma Whole-System, which features Gabriel’s work, a pesar. Helen is the Director of Institutional Advancement at the Institute for Educational Leadership in Washington, DC.

Advertisement

“Tutoring what one learns, and has shown to have mastered, becomes the occasion to learn in depth and to create a convivial community in the group.” – Câmara de gabriel

Gabriel, please summarize the goals of the tutorial networks.

Tutorial networks in public schools are a means to obviate a major distortion imposed on learners by the predominant culture that determines the themes that teachers and students should learn, and the times within which they should be mastered. Instead of allowing the free encounter of interested learners with a competent mentor, standard practices in classrooms force impersonal recitations of content to generally passive audiences. The known effect is not only lack of interest in the particular subject being presented, but the missed opportunity to practice learning academic subjects in earnest, with commitment, visible results and satisfaction – the foundations of the enduring ability to learn by oneself. Contrary to common practice, tutorial relationships in a classroom facilitate the matching of what is of interest to each student with what is available in the mentor’s repertoire. The immediate objection, from the conventional perspective, is that it would be well-nigh impossible for one teacher to match the interest of every student in a large group, even if the teacher is knowledgeable and willing to help. Tutorial networks deflect the objection, as all members in the group learn from one another. Tutoring what one learns, and has shown to have mastered, becomes the occasion to learn in depth and to create a convivial community in the group.

Tutorial networks were first started at the margins of a public school system, where chronic deficiencies in structure, transient teachers, e da pobreza regional, eram convites para experimentar inovações radicais, sem perturbar o resto das escolas. Como salas de aula regulares transformou em comunidades de aprendizagem e os alunos se tornaram capazes de tutoria que eles tinham dominado, As oportunidades de aprender multiplicado: alunos movido ansiosamente para escolas vizinhas para compartilhar o que sabia com os colegas, e, por sua vez, esses alunos e seus professores criou novas comunidades de aprendizagem. Em seguida, authorities changed from allowing a radical experiment in almost lost cases to promoting tutorial networks to improve learning in low performing, though better served schools. This way the transformation began to be seen as a large scale educational change.

Two major factors account for the transformation that already has touched thousands of public schools in Mexico: the acceptance of authorities in charge of the system, claro, but most striking, the inner conversion of teachers and students from passive receptors of external directives to managers of their own learning and active agents of change in neighboring schools. The newly discovered power among ordinary teachers and students, not only to learn, but also to teach, has proved to be the major force to sustain and spread tutorial networks in the school system.

As the basic competency of taking control of one’s own learning becomes regular practice among a growing number of educational actors, the possibilities of a more professional service increase.

“Once the competency of controlling and sharing one’s own learning becomes the basic link in an extended network of advisors, professores, students and even their families, the groundwork of an autonomous profession is laid out.” – Câmara de gabriel

What have been the benefits and what have been the challenges?

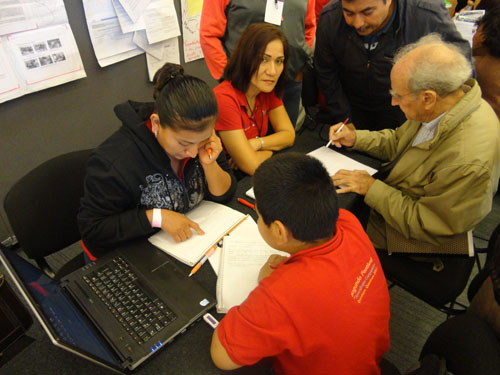

The major benefit has accrued to teachers and students who perceive, as never before, the satisfaction of achieving visible, valuable learning. A razão óbvia é a combinação perfeita de interesse e capacidade que obtém em diálogos tutorial quando tutor e tutee enfrentar um desafio comum. Básico para o sucesso é também o patrimônio da troca baseia na confiança mútua, verdade e compromisso. Tal troca invariavelmente conduz a conclusão, sempre satisfatório em um sentido real, nunca adiada para um futuro vago, e sempre aberto a novas realizações intelectuais. The evidence of good learning and the fruition of excellence come when the tutee becomes a tutor to fellow students, to family members and at times even to neighboring teachers and administrators. Exchanges among students of different schools in order to give and receive tutoring become natural, even necessary to demonstrate competency, increase common knowledge and extend the practice.

Once the competency of controlling and sharing one’s own learning becomes the basic link in an extended network of advisors, professores, students and even their families, the groundwork of an autonomous profession is laid out. Training, ensino, evaluating, managing school chores and administering resources are easily integrated and make possible the rendering of the quality service expected from a public school system.

The new relationships that started at the learning core create stronger social relationships within the school system, and in a very real sense democratize the institution, since the newly discovered power of every learner commands the process.

The challenge to the continuing expansion of tutorial networks, como sempre, is the ingrained habit of following tried patterns even if they do not deliver the promised results. It is the satisfactory experience of good results in face to face encounters that causes the inner conversion to learn in depth and enjoy sharing it.

“The fact that these networks have spread from dozens to thousands of schools in a manner of a few years and have been accepted by the educational establishment as a credible improvement approach, speaks to the power and evidence these tutorial structures have demonstrated to their communities and to the public at large. -Helen Janc Malone

Helen, what can we learn from this approach to school reform?

Tutorial networks in Mexico turn school reform on its head. As opposed to hoping educational change trickles down from national or regional policies and external pre-packaged reforms, tutorial networks create change from the grassroots level. The fact that these networks have spread from dozens to thousands of schools in a manner of a few years and have been accepted by the educational establishment as a credible improvement approach, speaks to the power and evidence these tutorial structures have demonstrated to their communities and to the public at large.

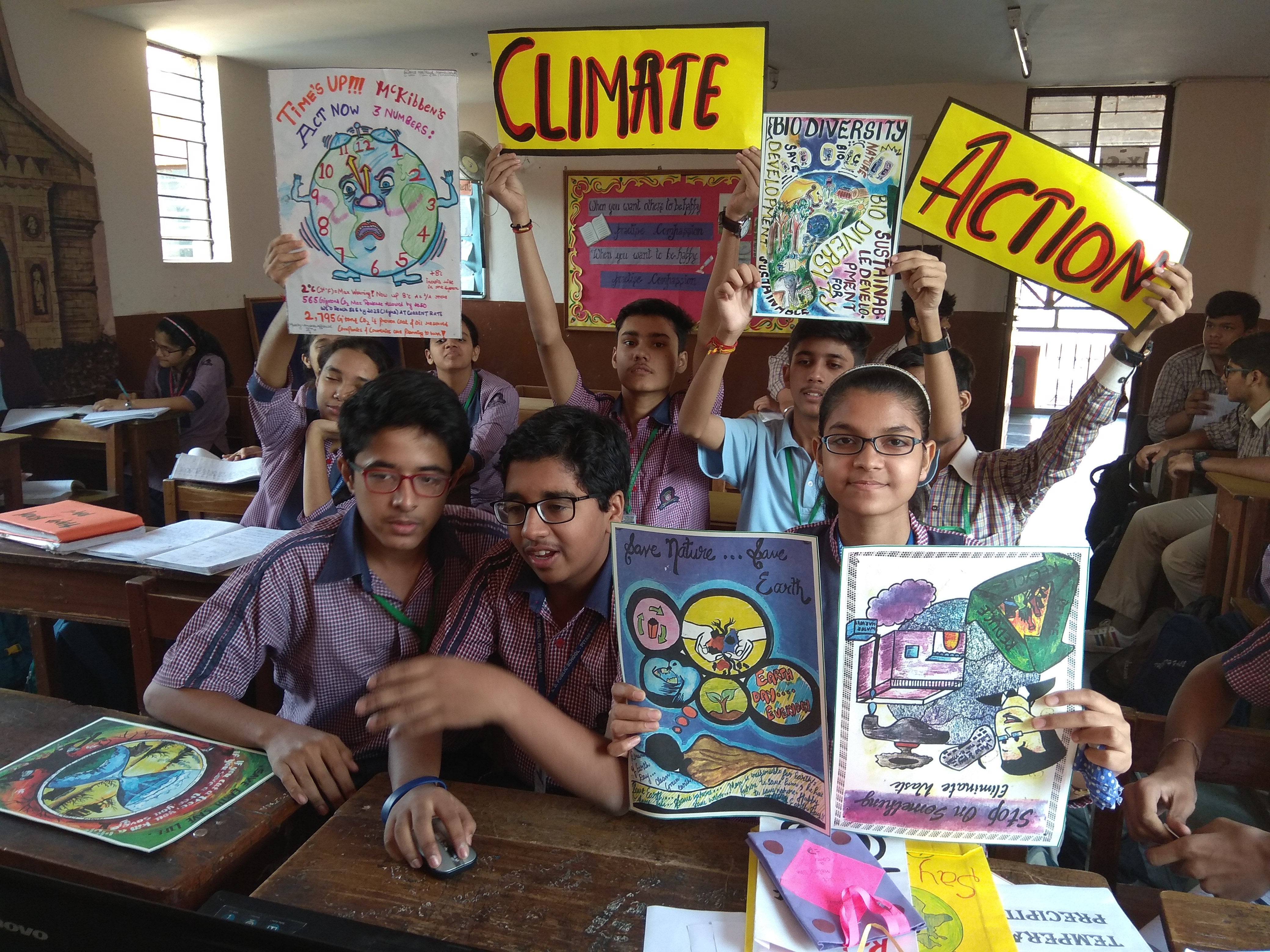

What is unique and innovative about the tutorial networks is that they put the learner and the process of learning at the center of the education endeavor, and focus on tutorial relationships as a driver for democratic, equitable learning environment, absent of traditional, grade-level, standardized, rigid structures that often disengage students. Taking agency for instructional delivery and ownership of learning is empowering and motivating for both the tutors and the tutees. There is a great sense of pride that comes from receiving personalized learning, mastering content and sharing that knowledge with peers. An added advantage of such a strategy has been the excitement that spreads beyond the school walls and spills out into the community, where families again begin to see schools as centers for learning and development. This is particularly evident where tutorial networks have been able to positively transform rural, high-poverty, low-performing schools.

Embora na U.S. há cada vez mais conversas sobre a aprendizagem personalizada, de aprendizagem digital, aprendizado mais profundo e afins, o mecanismo de entrega de conteúdo predominante na maioria das escolas continua a ser o tradicional, 20abordagem século XIX para o aprendizado. The tutorial networks give us an opportunity to start the conversation about what strategies engage students in the process of learning.

Helen Janc Malone, CM. Rubin, Câmara de gabriel

All Photos are courtesy of Jessica Trujano.

For more information see Leading Educational Change: Questões Globais, Desafios, e Lições sobre a Reforma Whole-System (Teachers College Press, 2013): http://store.tcpress.com/0807754730.shtml

Na busca Global para a Educação, se juntar a mim e líderes de renome mundial, incluindo Sir Michael Barber (Reino Unido), Dr. Michael Bloco (EUA), Dr. Leon Botstein (EUA), Professor Clay Christensen (EUA), Dr. Linda, Darling-Hammond (EUA), Dr. Madhav Chavan (Índia), Professor Michael Fullan (Canadá), Professor Howard Gardner (EUA), Professor Andy Hargreaves (EUA), Professor Yvonne Hellman (Holanda), Professor Kristin Helstad (Noruega), Jean Hendrickson (EUA), Professor Rose Hipkins (Nova Zelândia), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canadá), Honrosa Jeff Johnson (Canadá), Senhora. Chantal Kaufmann (Bélgica), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finlândia), Secretário de Estado Tapio Kosunen (Finlândia), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Bélgica), Professor Hugh Lauder (Reino Unido), Professor Ben Levin (Canadá), Senhor Ken Macdonald (Reino Unido), Professor Barry McGaw (Austrália), Shiv Nadar (Índia), Professor R. Natarajan (Índia), Dr. PAK NG (Cingapura), Dr. Denise Papa (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (Índia), Dr. Diane Ravitch (EUA), Richard Wilson Riley (EUA), Sir Ken Robinson (Reino Unido), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finlândia), Professor Manabu Sato (Japão), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OCDE), Dr. Anthony Seldon (Reino Unido), Dr. David Shaffer (EUA), Dr. Kirsten Immersive Are (Noruega), Chanceler Stephen Spahn (EUA), Yves Theze (Lycée Français EUA), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canadá), Professor Tony Wagner (EUA), Sir David Watson (Reino Unido), Professor Dylan Wiliam (Reino Unido), Dr. Mark Wormald (Reino Unido), Professor Theo Wubbels (Holanda), Professor Michael Young (Reino Unido), e Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) como eles exploram as grandes questões da educação imagem que todas as nações enfrentam hoje.

A Pesquisa Global para Educação Comunitária Página

C. M. Rubin é o autor de duas séries on-line lido pelo qual ela recebeu uma 2011 Upton Sinclair prêmio, “A Pesquisa Global para a Educação” e “Como vamos Leia?” Ela também é autora de três livros mais vendidos, Incluindo The Real Alice no País das Maravilhas.

Siga C. M. Rubin no Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Comentários Recentes