Gotta have Grit to succeed in a winner takes all world, right? But do you have Good Grit or Bad Grit?

Howard Gardner, world-acclaimed developmental psychologist and author of numerous books on intelligence and creativity, wants us to cultivate Good Grit in every school in the world. As part of his research endeavors at Harvard Graduate School of Education, he and his colleagues have created “The Good Project.” Jeffrey Beard (Former Director General of the International Baccalaureate Organization, now Chairman and Founder of Global Study Pass) is a strong proponent.

So, how do we identify Bad Grit versus Good Grit? What are some of the contemporary examples of Good Grit? How can having Good Grit help students compete in the global marketplace? What are the most realistic ways in educational contexts to foster the value system so essential to Good Grit?

Howard and Jeff share their answers with us in today’s edition of The Global Search for Education.

How can one determine if a project has Bad Grit or if Grit is being used to destructive ends?

Jeff: Determining whether a project has Good Grit or Bad Grit is one of investigation; reading the mission and values statement of the project; what are they trying to do and WHY? That’s only one step as sometimes what looks good may in fact be the devil in disguise. The next step is to talk with staff members and those that have benefited from the project’s work to see whether or not the mission and values are being delivered.

There are also educational organizations that have institutional Grit built into their DNA. Think about the International Baccalaureate (IB) and the United World Colleges (UWC), both of which have been particularly successful as a delivery vehicle for Good Grit because they combine an educational philosophy with a mission aimed at creating young people who make a difference in the world. Indeed, the mission of UWC aims to “make education a force to unite people, nations, and cultures for peace and a sustainable future.”

Howard: At the personal activity level, motivation is certainly important — is the goal constructive or destructive? But the proof is in the pudding. You may strive and sweat to write well (a laudable goal), but if in the end you are writing propaganda — the Big Lie — then grit is serving a bad end.

Can you change the ends, once a negative system is in place?

Howard: On an individual level, sure. Let’s say that you’ve learned to write well but you are writing copy to convince kids to eat sugar-saturated cereals. You could leave the ad agency and start a blog on health living. As a youth, Malcolm X carried out petty crimes, but eventually he provided positive leadership.

Jeff: Based on my experience, I believe it is difficult, if not impossible, to change a negative system into a positive one. The best examples that have tried this are the social ones, like the Arab Spring. This began in December 2010 as a revolutionary wave of demonstrations, protests, riots, and civil wars in an attempt to replace a dictatorship (or negative system) with a democracy (a positive system). As we’ve seen, those struggles continue, and will continue for some time before they are (hopefully) changed for the better.

What are some of the contemporary examples of Good Grit?

Howard: I admire young people who have become social entrepreneurs, working primarily in the non-profit sector. They seek to solve problems in their community and to help individuals — young and old — who are not in a position to ‘go it alone’. I salute college graduates who work for Teach for America or for KIPP, and not just to pad their resume.

An outstanding example in the 20th century was Nelson Mandela. He spent 27 years in prison on Robben Island, then brought about a peaceful end to apartheid, and, when inaugurated as President, invited his jailer to dinner. Other notable examples are Marion Wright Edelman of the Children’s Defense Fund and Ralph Nader, consumer advocate for six decades.

Jeff: Many of the not-for-profit organizations are aimed toward Good Grit. The United Nations, at its core, has this value (think of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, passed in 1948, which was motivated by the experiences of the preceding world wars; it was the first time that countries agreed on a comprehensive statement of inalienable human rights). Think also of Doctors Without Borders, the International Red Cross, and the Peace Corps, the latter being initiated by President Kennedy in 1961. All demonstrate Good Grit.

How can having Good Grit help students to compete in the global marketplace?

Howard: It all depends on the kind of world in which you want to live. If you simply want to have the most toys at the end of life, you might get away with Bad or Compromised Grit. But if you pursue goals beyond self-aggrandizement, then you can do well both for yourself and for the world. And even if you don’t aim to change the world, being truthful and trustworthy serve you well in every marketplace.

Jeff: In today’s global economy, jobs will increasingly go to those workers who achieve the best education, but also demonstrate most evidence of Good Grit. Young people are no longer competing with their peers in their local district or state — they are competing with their peers across the world.

As Tom Friedman likes to point out, average is over. Today’s students need to find that extra difference now — their unique value contribution that will make them stand out from their global peers. Put simply, students who show more Good Grit today will be the ones hired, and they will be the ones making a difference in our world, for the betterment of tomorrow’s society.

What are the most realistic ways in educational contexts to foster the value system so essential to Good Grit?

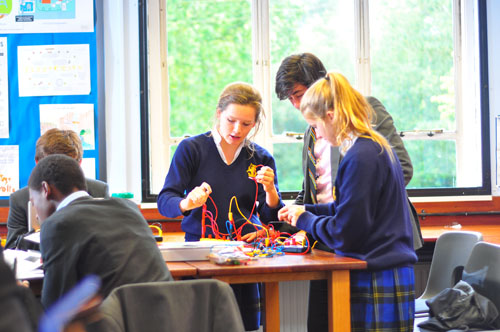

Jeff: I think there are ways to systematically develop Good Grit in young people as they grow up in this very competitive “winner-takes-all” world. Students can best develop this through a combination of a quality, holistic education coupled with experiential interventions, such as a study abroad experience.

There are two attributes that I believe are fundamental to Good Grit. The first attribute is a defining characteristic called mind-set. It is an inherent “I can” belief that, when developed in a positive manner, is immensely powerful. The second attribute is the wonderful phenomenon that occurs when students develop their own “global citizenship conscience.” This happens most profoundly through cultural experiential learning as an integral part of the education process.

The incubation period takes time, and it is most powerfully embedded during the secondary years. The process includes imbuing young students with an appreciation and a valuing of differences in others. It involves students examining ideas that challenge their own, and evaluating these ideas critically. And just as importantly, it includes students engaging in thought, discussion and active learning. This is what has made the distinctive difference in both the IB and UWC educational systems — the ability to incorporate this active learning as a fundamental part of the education offer.

Howard: Institutions exert powerful effects on their members. Except for the family (not always a positive model), schools are the examples par excellence for Grit, in its manifold varieties. When young people see older persons (students, teachers, or administrators) who work hard and well for positive ends, who are contemplative about what has worked and what not, and who strive to do better — and who look to students to do the same — then we can anticipate admirable individuals with admirable values. No one says this is easy to attain — but the rewards make it worthwhile. See the Good Work Toolkit.

For more information on Howard Gardner

For more information on Jeffrey Beard

(Photos are courtesy of Global Study Pass)

Join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. MadhavChavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. EijaKauppinen (Finland), State Secretary TapioKosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Professor Ben Levin (Canada), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor PasiSahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (LyceeFrancais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today.

The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland, is the publisher of CMRubinWorld, and is a Disruptor Foundation Fellow.

Recent Comments