Education is one of the most effective tools we have to combat poverty.

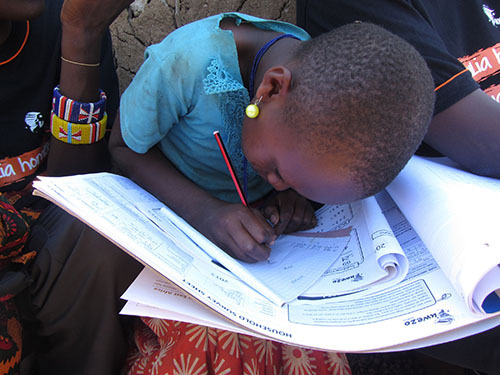

Il ya quelques années, my daughter and I worked with AIDS orphans in schools in Tanzania. For us it was both an inspiring experience and a tragic example of the challenges that strike hardest on people in poor countries.

The Ebola crisis is another grim reminder. The number of Ebola cases in Africa are predicted to climb to 10,000 a week by the World Health Organization. With death rates at 70 pour cent, teachers and social workers on the ground are expressing grave concern about the thousands of children being orphaned by the outbreak. (See Patrick Sawer of The Telegraph).

Dans La recherche globale pour l'éducation aujourd'hui, I’ve invited Dr. Sara Ruto (Directeur régional de Uwezo, une initative de littératie et de numératie au Kenya, Tanzanie et l'Ouganda), Aarnout Brombacker (Founding partner of the South African mathematics consultancy, Brombacher and Associates), Dylan Wray (Co-founder of Shikaya, which supports the development of teachers in South Africa), and Senator David Coltart (Minister of Education, Arts and Culture for Zimbabwe from 2009 à 2013) to share their perspectives and solutions for bringing about transformative change in education in Africa.

The 21st century is the age of shifting skills in our world – skills required for the jobs of the future. The role of the educator is critical at this time. Where in Africa are you seeing countries really trying hard to improve their education systems? What are the strategies that you find encouraging?

Dylan: I think many African countries are realizing that if the economic investment and growth we are currently seeing is to continue, education systems need to improve very quickly.

Most countries are not getting this right. Mauritius seems to be on the right path. They have consistently come out on top on the education indicators of the Mo Ibrahim African Good Governance Index. In Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania, les structures qu'ils mettent en place pour la collaboration autour de l'amélioration de leurs systèmes d'éducation offre l'espoir. L'Ouganda et le Kenya sont l'objet de révisions curricula, qui visent à offrir une éducation du 21e siècle plus pertinent. Au Kenya, écoles privées augmentent rapidement en tant que parents regardent au-delà de l'état pour offrir une qualité.

Aarnout: Je vois beaucoup d'efforts pour améliorer les systèmes d'éducation qui mettent l'accent sur le curriculum, matériaux et infrastructures. Bien que ces éléments sont importants, I think there are not enough efforts that focus on the teacher as the locus of change and improvement.

Ce Sera: Africa is resplendent with success stories. Malheureusement, many are small pilot projects that have not satisfied the scale criteria. One example is Cape Verde where almost all children access school from the early preschool years through to secondary. Rwanda has proved that your most rural school can enjoy the benefits of technology. At the core of an education system is the teacher, and South Africa paves the way here with teachers as highly paid as those in Germany and Switzerland.

David: There are sadly very few countries in Africa that are investing sufficiently in education. In most African countries, far more money is spent on large bloated governments and excessive defense expenditure. Botswana and South Africa have invested fairly heavily in education, and Zimbabwe in its first decade post-independence did the same. Until education is made an absolute budgetary priority throughout Africa, the massive challenges facing the sector will not be addressed.

Like countries all over the world, each African country has its own unique challenges and issues facing its education systems. But are there also common challenges that extend across the continent’s borders? Quels problèmes croyez-vous êtes unique sur le continent africain? Quels problèmes pensez-vous que part l'Afrique avec le reste du monde?

Dylan: Zimbabwe avait un très bon système d'éducation en place dans les années 1980 et la plupart des années 1990. L'instabilité politique a porté un coup sévère à la prestation de l'éducation au Zimbabwe, mais il est maintenant de voir l'amélioration. Ils ont vu les choses fonctionnent dans le passé, mais de nombreux pays en Afrique ne ont pas eu cette expérience. Sans cette, comment savez-vous même pas par où commencer?

défis de l'éducation qui se étendent à travers les frontières africaines comprennent un manque de ressources physiques telles que les salles de classe, ordinateurs et assainissement. Et il ya les impacts les plus profondes de la pauvreté qui transcendent les systèmes. Dans de nombreux pays en Afrique, les enfants viennent à l'école le ventre vide. Les enfants qui ont faim ne apprennent pas.

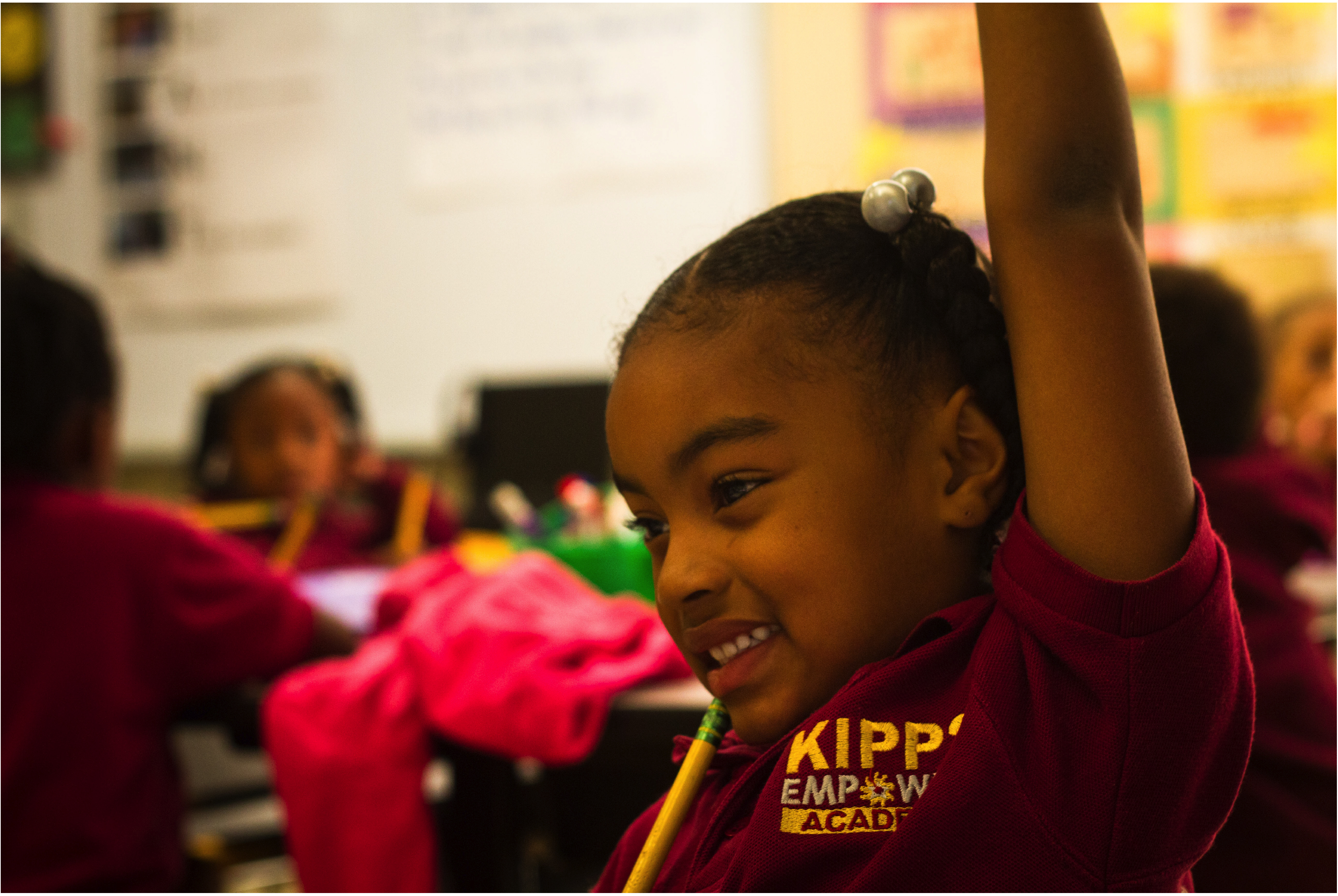

Un défi qui ne est pas propre à l'Afrique est le manque de bien-formés, knowledgeable, et enseignants passionnés. Ce est le défi que la plupart des pays à travers le monde font face, and it is what holds the solution for improving education on a global scale. It is teachers who make or break the system.

Ce Sera: The African continent is almost all united in a colonial experience that left a heavy foreign based curriculum and ethos that has taken more than three decades to shake off. Diversity within, especially with regard to languages, has delayed crucial decisions. Perhaps more than other places, we have two parallel knowledge systems that do not make any attempt to complement each other – l'officielle en milieu scolaire, et la connaissance de la communauté. L'Afrique continue d'explorer comment le système éducatif peut être rendue plus réactive, peut inculquer des valeurs et des compétences qui permettent aux enfants de réussir, peut être les institutions plutôt que des centres de forage apprentissage.

Aarnout: Une réponse facile comprend un sous-financement en termes de matériaux d'apprentissage, la qualité des salles de classe, et de l'infrastructure d'enseignement général. Cependant, le plus grand défi est d'environ la pédagogie. La pratique actuelle est axée sur la mémorisation plutôt que de développer la compréhension. My sense is that while this is not unique to Africa, it may be more exaggerated in Africa. Bringing about a change in what it means to teach involves a fundamental revision of the predominant mental model.

David: In many countries throughout the world there is insufficient investment in education. Primarily, this has resulted in the undermining of the teaching profession in many countries, with some key exceptions such as Singapore and Finland. It has also resulted in educational institutions being underfunded throughout the world. However the educational funding crisis is even more acute in Africa; teachers are often despised and dreadfully underpaid. The teaching profession is one of the least attractive and worst paid professions on the continent.

If you were able to invest more time and money in reforming Africa’s education systems, where would you start?

Dylan: I would do everything possible to ensure that new, knowledgeable, passionate and dedicated teachers enter the system. A focus also needs to be on improving the conditions of service for teachers and, crucially, on improving the status of the profession.

I would focus my attention in the system on early childhood development and the foundation years of primary school. The state needs to step in here and begin the learning early on.

Aarnout: I would take a long-term view and start in the early years with a focus on teacher development. I would invest in both pre-service and in-service teacher training, supporting teachers to implement more research based teaching methodologies.

Ce Sera: On peut soutenir que les systèmes d'éducation les plus dysfonctionnelles, en particulier les écoles publiques, se trouvent en Afrique. Ceci est lié à un problème plus important qui est double: a washed away value system and lack of imagination. It is herein I would invest my time and money. Values do not rest on the state; they rest in the individual and are ‘lived’. Often they are called the ‘soft skills’ of having integrity, being accountable, and truthful. If the teachers lived this, together with parents and children, we would have the recipe to address the core issues. System reforms are missing out on the core problem, and investing more in the symptoms.

David: I would start with the teaching profession; investing more money in their training institutions, in their housing conditions and of course in their general conditions of service. Until the teaching profession is made more attractive in Africa, African countries will not see their educational systems improve. Deuxièmement, I would focus more resources on the upgrading of curricula. Finally I would greatly increase investment in the maintenance of existing schools, the construction of new schools and the provisions of educational materials such as textbooks.

Dr. Sara Ruto – Pour plus d'informations

Aarnout Brombacher – Pour plus d'informations

Dylan Wray – Pour plus d'informations

Le sénateur David Coltart – Pour plus d'informations

(Toutes les photos sont une gracieuseté du Dr. Sara Ruto and Dylan Wray)

Rejoignez-moi et leaders d'opinion de renommée mondiale dont Sir Michael Barber (Royaume-Uni), Dr. Michael Bloquer (États-Unis), Dr. Leon Botstein (États-Unis), Professeur Clay Christensen (États-Unis), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (États-Unis), Dr. MadhavChavan (Inde), Le professeur Michael Fullan (Canada), Professeur Howard Gardner (États-Unis), Professeur Andy Hargreaves (États-Unis), Professeur Yvonne Hellman (Pays-Bas), Professeur Kristin Helstad (Norvège), Jean Hendrickson (États-Unis), Professeur Rose Hipkins (Nouvelle-Zélande), Professeur Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honorable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgique), Dr. EijaKauppinen (Finlande), Le secrétaire d'Etat TapioKosunen (Finlande), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgique), Professeur Hugh Lauder (Royaume-Uni), Professeur Ben Levin (Canada), Seigneur Ken Macdonald (Royaume-Uni), Professeur Barry McGaw (Australie), Shiv Nadar (Inde), Professeur R. Natarajan (Inde), Dr. PAK NG (Singapour), Dr. Denise Pape (États-Unis), Sridhar Rajagopalan (Inde), Dr. Diane Ravitch (États-Unis), Richard Wilson Riley (États-Unis), Sir Ken Robinson (Royaume-Uni), Professeur PasiSahlberg (Finlande), Professeur Manabu Sato (Japon), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OCDE), Dr. Anthony Seldon (Royaume-Uni), Dr. David Shaffer (États-Unis), Dr. Kirsten immersive, (Norvège), Chancelier Stephen Spahn (États-Unis), Yves Thézé (LyceeFrancais États-Unis), Professeur Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professeur Tony Wagner (États-Unis), Sir David Watson (Royaume-Uni), Professeur Dylan Wiliam (Royaume-Uni), Dr. Mark Wormald (Royaume-Uni), Professeur Theo Wubbels (Pays-Bas), Professeur Michael Young (Royaume-Uni), et le professeur Zhang Minxuan (Chine) alors qu'ils explorent les grandes questions d'éducation de l'image que toutes les nations doivent faire face aujourd'hui.

La recherche globale pour l'éducation communautaire page

C. M. Rubin est l'auteur de deux séries en ligne largement lecture pour lequel elle a reçu une 2011 Upton Sinclair prix, “La recherche globale pour l'éducation” et “Comment allons-nous savoir?” Elle est également l'auteur de trois livres à succès, Y compris The Real Alice au pays des merveilles, est l'éditeur de CMRubinWorld, et est une fondation perturbateurs Fellow.

Suivez C. M. Rubin sur Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Commentaires récents