Education is one of the most effective tools we have to combat poverty.

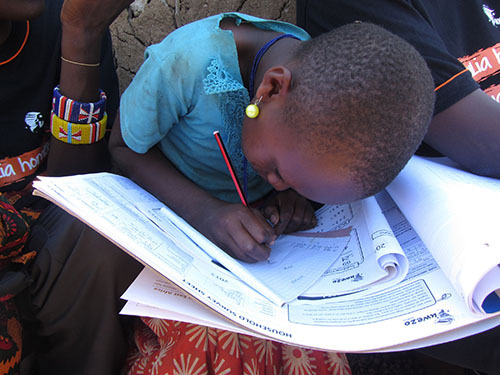

A few years ago, my daughter and I worked with AIDS orphans in schools in Tanzania. For us it was both an inspiring experience and a tragic example of the challenges that strike hardest on people in poor countries.

The Ebola crisis is another grim reminder. The number of Ebola cases in Africa are predicted to climb to 10,000 a week by the World Health Organization. With death rates at 70 per cent, teachers and social workers on the ground are expressing grave concern about the thousands of children being orphaned by the outbreak. (See Patrick Sawer of The Telegraph).

In Il Global Ricerca per l'Educazione oggi, I’ve invited Dr. Sara Ruto (Regional Manager di Uwezo, una alfabetizzazione initative in Kenya, Tanzania e Uganda), Aarnout Brombacker (Founding partner of the South African mathematics consultancy, Brombacher and Associates), Dylan Wray (Co-founder of Shikaya, which supports the development of teachers in South Africa), and Senator David Coltart (Minister of Education, Arts and Culture for Zimbabwe from 2009 a 2013) to share their perspectives and solutions for bringing about transformative change in education in Africa.

The 21st century is the age of shifting skills in our world – skills required for the jobs of the future. The role of the educator is critical at this time. Where in Africa are you seeing countries really trying hard to improve their education systems? What are the strategies that you find encouraging?

Dylan: I think many African countries are realizing that if the economic investment and growth we are currently seeing is to continue, education systems need to improve very quickly.

Most countries are not getting this right. Mauritius seems to be on the right path. They have consistently come out on top on the education indicators of the Mo Ibrahim African Good Governance Index. In Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania, the structures they are putting in place for collaboration around improving their education systems offers hope. Both Uganda and Kenya are undergoing curricula revisions, which are aimed at delivering a more relevant 21st century education. In Kenya, private schools are increasing rapidly as parents look beyond the state to deliver quality.

Aarnout: I see a lot of efforts to improve education systems that focus on curriculum, materials and infrastructure. While these are important, I think there are not enough efforts that focus on the teacher as the locus of change and improvement.

Sara: Africa is resplendent with success stories. Sfortunatamente, many are small pilot projects that have not satisfied the scale criteria. One example is Cape Verde where almost all children access school from the early preschool years through to secondary. Rwanda has proved that your most rural school can enjoy the benefits of technology. At the core of an education system is the teacher, and South Africa paves the way here with teachers as highly paid as those in Germany and Switzerland.

David: There are sadly very few countries in Africa that are investing sufficiently in education. In most African countries, far more money is spent on large bloated governments and excessive defense expenditure. Botswana and South Africa have invested fairly heavily in education, and Zimbabwe in its first decade post-independence did the same. Until education is made an absolute budgetary priority throughout Africa, the massive challenges facing the sector will not be addressed.

Like countries all over the world, each African country has its own unique challenges and issues facing its education systems. But are there also common challenges that extend across the continent’s borders? Quali problemi credi siete unici al continente africano? Quali problemi credi Africa condivide con il resto del mondo?

Dylan: Zimbabwe aveva un sistema educativo molto bene in posto nel 1980 e gran parte degli anni 1990. L'instabilità politica ha inferto un duro colpo alla consegna formazione in Zimbabwe, ma è ora vedendo miglioramento. Hanno visto le cose in passato, ma molti paesi in Africa non hanno avuto questa esperienza. Senza questo, come si sa nemmeno da dove cominciare?

Sfide Istruzione che si estendono oltre i confini africani sono la mancanza di risorse fisiche, come aule, computer e servizi igienici adeguati. E ci sono gli impatti più profonde della povertà che attraversano i sistemi. In molti paesi in Africa, i bambini vengono a scuola a stomaco vuoto. I bambini che hanno fame non imparano.

Una sfida che non riguardano solo l'Africa è la mancanza di ben addestrato, knowledgeable, e insegnanti appassionati. Questa è la sfida che la maggior parte dei paesi di tutto il mondo affrontano, and it is what holds the solution for improving education on a global scale. It is teachers who make or break the system.

Sara: The African continent is almost all united in a colonial experience that left a heavy foreign based curriculum and ethos that has taken more than three decades to shake off. Diversity within, especially with regard to languages, has delayed crucial decisions. Perhaps more than other places, we have two parallel knowledge systems that do not make any attempt to complement each other – quello ufficiale scolastica, e la conoscenza della comunità. Africa continua a esplorare come il sistema di istruzione può essere reso più reattivo, può infondere valori e competenze che consentono ai bambini di avere successo, possono essere istituzioni, piuttosto che centri di foratura di apprendimento.

Aarnout: Una risposta semplice include carenza di risorse in termini di materiali didattici, la qualità delle aule, e l'infrastruttura generale della scuola. Tuttavia, la sfida più grande è di circa pedagogia. La prassi attuale è focalizzata sulla memorizzazione piuttosto che sviluppare la comprensione. My sense is that while this is not unique to Africa, it may be more exaggerated in Africa. Bringing about a change in what it means to teach involves a fundamental revision of the predominant mental model.

David: In many countries throughout the world there is insufficient investment in education. Primarily, this has resulted in the undermining of the teaching profession in many countries, with some key exceptions such as Singapore and Finland. It has also resulted in educational institutions being underfunded throughout the world. However the educational funding crisis is even more acute in Africa; teachers are often despised and dreadfully underpaid. The teaching profession is one of the least attractive and worst paid professions on the continent.

If you were able to invest more time and money in reforming Africa’s education systems, where would you start?

Dylan: I would do everything possible to ensure that new, knowledgeable, passionate and dedicated teachers enter the system. A focus also needs to be on improving the conditions of service for teachers and, crucially, sul miglioramento dello stato della professione.

Vorrei concentrare la mia attenzione nel sistema per lo sviluppo della prima infanzia e gli anni di fondazione della scuola primaria. Lo Stato deve intervenire qui e iniziare l'apprendimento nella fase iniziale.

Aarnout: Vorrei avere una visione a lungo termine e iniziare nei primi anni con un focus sulla formazione degli insegnanti. Vorrei investire sia in pre-servizio e la formazione in servizio degli insegnanti, sostenere gli insegnanti a realizzare più metodologie didattiche di ricerca basato.

Sara: Probabilmente i sistemi di istruzione più disfunzionali, scuole in particolare quelle pubbliche, si trovano in Africa. Questo è legato a un problema più grande che è duplice: un sistema di valori lavato via e la mancanza di immaginazione. It is herein I would invest my time and money. Values do not rest on the state; they rest in the individual and are ‘lived’. Often they are called the ‘soft skills’ of having integrity, being accountable, and truthful. If the teachers lived this, together with parents and children, we would have the recipe to address the core issues. System reforms are missing out on the core problem, and investing more in the symptoms.

David: I would start with the teaching profession; investing more money in their training institutions, in their housing conditions and of course in their general conditions of service. Until the teaching profession is made more attractive in Africa, African countries will not see their educational systems improve. In secondo luogo, I would focus more resources on the upgrading of curricula. Finally I would greatly increase investment in the maintenance of existing schools, the construction of new schools and the provisions of educational materials such as textbooks.

Dr. Sara Ruto – Per ulteriori informazioni

Aarnout Brombacher – Per ulteriori informazioni

Dylan Wray – Per ulteriori informazioni

Il senatore David Coltart – Per ulteriori informazioni

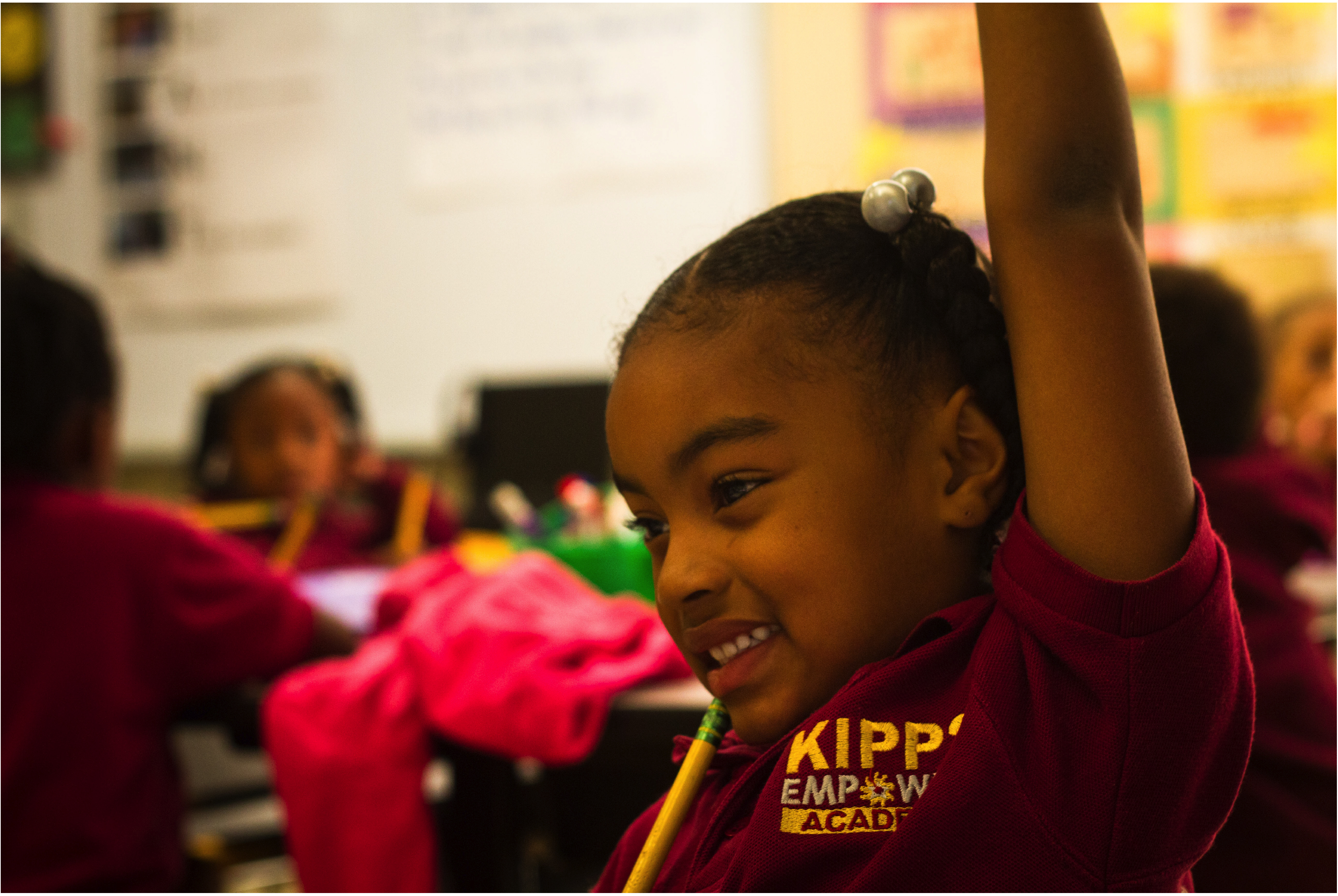

(Tutte le foto sono per gentile concessione di Dr. Sara Ruto and Dylan Wray)

Unitevi a me e leader di pensiero di fama mondiale tra cui Sir Michael Barber (Regno Unito), Dr. Michael Block (Stati Uniti), Dr. Leon Botstein (Stati Uniti), Il professor Argilla Christensen (Stati Uniti), Dr. Linda di Darling-Hammond (Stati Uniti), Dr. MadhavChavan (India), Il professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Il professor Howard Gardner (Stati Uniti), Il professor Andy Hargreaves (Stati Uniti), Il professor Yvonne Hellman (Paesi Bassi), Il professor Kristin Helstad (Norvegia), Jean Hendrickson (Stati Uniti), Il professor Rose Hipkins (Nuova Zelanda), Il professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Onorevole Jeff Johnson (Canada), Sig.ra. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgio), Dr. EijaKauppinen (Finlandia), Sottosegretario di Stato TapioKosunen (Finlandia), Il professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgio), Il professor Hugh Lauder (Regno Unito), Il professor Ben Levin (Canada), Signore Ken Macdonald (Regno Unito), Il professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Il professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. PAK NG (Singapore), Dr. Denise Papa (Stati Uniti), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (Stati Uniti), Richard Wilson Riley (Stati Uniti), Sir Ken Robinson (Regno Unito), Il professor PasiSahlberg (Finlandia), Il professor Manabu Sato (Giappone), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OCSE), Dr. Anthony Seldon (Regno Unito), Dr. David Shaffer (Stati Uniti), Dr. Kirsten Immersive Are (Norvegia), Cancelliere Stephen Spahn (Stati Uniti), Yves Theze (LyceeFrancais Stati Uniti), Il professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Il professor Tony Wagner (Stati Uniti), Sir David Watson (Regno Unito), Professor Dylan Wiliam (Regno Unito), Dr. Mark Wormald (Regno Unito), Il professor Theo Wubbels (Paesi Bassi), Il professor Michael Young (Regno Unito), e il professor Zhang Minxuan (Porcellana) mentre esplorano le grandi questioni educative immagine che tutte le nazioni devono affrontare oggi.

Il Global Ricerca per l'Educazione della Comunità Pagina

C. M. Rubin è l'autore di due ampiamente lettura serie on-line per il quale ha ricevuto una 2011 Premio Upton Sinclair, “Il Global Ricerca per l'Educazione” e “Come faremo a Leggere?” Lei è anche l'autore di tre libri bestseller, Compreso The Real Alice in Wonderland, è l'editore di CMRubinWorld, ed è un disgregatore Foundation Fellow.

Segui C. M. Rubin su Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Commenti recenti