“I like to think that we’ll find ways to partner with our AI creations — to enhance life, bringing about more shared equity and prosperity, and to enable humans to connect more deeply with one another.” — Chris Messina

Many know Chris Messina as the guy who invented the Twitter hashtag, but Chris Messina has actually spent the last decade being a game changer with many other innovations including Drupal, Firefox, Flock, BarCamp, Google+ , Uber Developer’s Platform and open web communities, to name but a few. He is also the Co-Founder of Molly.com. The Tribeca Disruptive Innovation Awards (TDIA) has named him a 2018 honoree. Helmed by co-founder, Craig Hatkoff, in collaboration with Professor Clayton Christensen, the TDIA celebrates innovation with a specific focus on breakthroughs occurring at the intersection of tech and culture. In an age where social media technologies have transformed how we communicate, how we find out about world issues, and more importantly, how we take action on them, it seemed like a timely idea to chat with Chris about the good and the bad of our tools of the moment.

On August 23rd, 2007, you tweet the first hashtag and…

I tweeted the first hashtag, and two days later I wrote up a pretty exhaustive proposal for how I thought it could work, complete with screenshots. So, it wasn’t like this was a throw-away idea for me… I’d given it some strong consideration.

When I took the idea to Twitter’s Biz Stone, though, he rejected it right away. I realize he was probably stressed because there was some server meltdown going down and didn’t have any spare attention to entertain some random idea for the service… but the message I got was, “That idea is way too nerdy. No one’s ever going to use hashtags. We’ll use algorithms to solve the problem.”

I figured he knew better than I did, but I was still internally convinced that there was merit in my idea, and left, disappointed but undeterred.

“It is imperative that we are able to step away from the industrial hamster treadmill that we’ve built for ourselves and think to the kind of society and civilization we want to inhabit in the future. While those conversations are beginning to take shape today, they’re certainly not widespread yet.” –– Chris Messina

When did you know the “hashtag” was part of the popular culture and what did you learn from this journey?

For quite a while, hashtags were only used by people in Silicon Valley and me, if at all. But a curious thing happened when the Tea Party realized that Twitter could be used to promote their agenda and message… and that hashtags were an effective organizing tool. Specifically, in 2008, conservatives used the #dontgo hashtag to encourage their congressional reps to stay and vote on an energy bill. I happened to see this, or a related hashtag, while driving somewhere in upstate rural California and knew that hashtags had made the leap from the technorati to the mainstream.

After that, I started to notice hashtags appearing in more and more places — and took photos to document their rise, from ads on buses to movie trailers and posters, to bumper stickers, and TV ads, and beyond. There’s been skywriters that have put hashtags in the clouds and of course newly weds recording their ceremony in the sand.

Given the initial skepticism, I learned to trust my gut, be patient, and have faith in elegantly simple solutions to human problems that people might suppose would be better solved by sophisticated technology. Ultimately people prefer solutions that are easy to master but can also be used to generate complex outcomes.

“We shape our tools and then our tools change us.” Today we have so many social media tools at our fingertips. How does humanity, specifically youth who use them the most, stay in control in this context?

I listened to an amazing piece from the New Yorker on Andy Clark’s work on the extended mind, and it pairs so well with your McLuhan quote that I can’t not mention it (the subtitle is literally “The tools we use to help us think—from language to smartphones—may be part of thought itself”). Slowly we’re eroding the illusion that each human is a stand-alone vessel, independent from its surrounding environment, and separate from other thinking and acting agents around it. Instead, we are all part of overlapping networks of meaning, and our ability to make sense of reality comes down to how we interpret the information that comes from the conversations we have. And when I think of “conversations”, I don’t merely mean verbal communication, but the negotiation of meaning between two distinct entities.

To try to make this less abstract — let’s say you went on an amazing vacation and you verbally tell me all about it after you return. That’s great, and will no doubt inspire vivid imagery in my mind, largely drawn from my own experiences. But let’s say instead you pull out your phone and show me some photos. Now I have a clearer set of images to draw from. But perhaps while you were on vacation, I was watching videos you shot through Instagram Stories that you published. And then maybe we also FaceTimed and I asked you to pan around and point at things that I wanted to see. And let’s say that we really went crazy and I got a VR headset and you connected me in real-time with a 3D camera extension you hooked up to your phone so that I had the same 360 view as you…! You can see how each successive improvement to the depth, richness, and immersiveness of the experience brings me closer and closer to your reality, which means that I can understand what you experienced with increasing vibrancy and fidelity.

The ability to go from a lossy retelling of your experience to one with vivid accuracy is new, and may help us connect more deeply with one another’s experiences in the world. At the same time, our ability to synthesize images and experiences in virtual reality, etc. also means that we must become more aware of our own subjective experience, and how our minds interpret the information we receive.

Therefore, “staying in control” isn’t necessarily the objective, but gaining increasing self – and situational – awareness are. Can we become aware of when our psychology has being hijacked without our awareness or consent? Can we use the same tactics on ourselves, to manipulate ourselves into improving our behavior or health with subtle nudges? This is really the opportunity and the threat that we must confront in today’s media environment.

“More and more children will grow up talking to a voice assistant of some kind (like Alexa or Google Assistant) and those same kids will live in hybrid versions of reality — mixes of the digital and the authentic — and will increasingly care less about which is which.” — Chris Messina

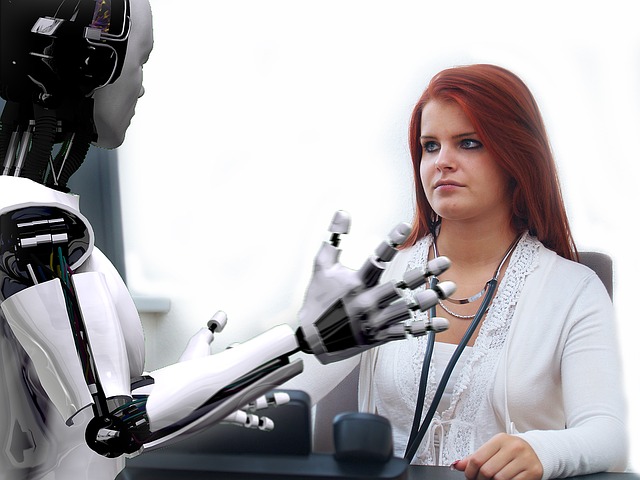

The Robots are here with smarter robots ahead. Can you talk about your hopes and fears about the future?

I like to think that we’ll find ways to partner with our AI creations — to enhance life, bringing about more shared equity and prosperity, and to enable humans to connect more deeply with one another. Ideally, we will recognize that we are living in an age of great abundance, even though it is not equally distributed, and that our obligation and opportunity is to lift up the human race through the effective and just application of technology.

But, I also fear that our biology and psychology isn’t quite ready to let go of the lessons that seem hard coded from our collective experience of surviving eons of scarcity. We can see that the game of capitalism prefers one set of amoral outcomes — to reduce costs and increase profits over time, and it prefers zero sum outcomes. In that world, humans are ultimately a cost to be eliminated because our fitness function to adapt and survive, creatively isn’t built into the calculus of the free market. So long as there is a winner, the market doesn’t necessarily seem concerned if the market continues to exist.

Therefore, it is imperative that we are able to step away from the industrial hamster treadmill that we’ve built for ourselves and think to the kind of society and civilization we want to inhabit in the future. While those conversations are beginning to take shape today, they’re certainly not widespread yet.

How will molly.com innovate our world? How will it make my world a better place?

The underlying intention of Molly is to connect people by inspiring curiosity, self-knowledge, and mutuality. It’s totally a product of my West Coast experience, but I think it’s important that the next generation of social technologies emphasize connection not just with machines but between people, including with themselves.

We’re at the dawn of an incredibly important shift in computing — where they will start to act and behave more like us, and be able to understand us in our own words and gestures, and where previously what separated us from our devices was obvious, those lines will continue to erode. More and more children will grow up talking to a voice assistant of some kind (like Alexa or Google Assistant) and those same kids will live in hybrid versions of reality — mixes of the digital and the authentic — and will increasingly care less about which is which.

We shouldn’t be unnecessarily nostalgic about what we lose as these changes permeate, but we should observe them scrupulously and take note of how they alter the way we treat each other and ourselves. We’ve already seen how social media creates a warped sense of reality for many people who bathe in its echolalic feeds… when we integrate those feedback loops and mass communication potential into the surface of reality, our minds (and how we define them) will be altered for good — and I hope Molly helps make sure that is it for good, and not ill.

C.M. Rubin and Chris Messina

The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland, is the publisher of CMRubinWorld and is a Disruptor Foundation Fellow.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments