Research has sought to understand why more boys than girls excel in math and science in the U.S. “The gender gap in math and science achievement in Finland is rather equal between boys and girls. Finns give a strong focus to math and science in elementary grades supported by well-trained primary school teachers with masters degrees who emphasize both the experimental and experiential nature of learning math and science,” states Pasi Sahlberg, author of Finnish Lessons: What can the World learn from Educational Change in Finland?

According to PISA and Sahlberg’s book, fewer pupils think math is difficult in Finland. Interestingly, math textbooks, which are written by teachers, are only a fraction of the size of similar textbooks in the U.S. In the 1990s, Finland launched a campaign to clean all gender-biased items from textbooks. Illustrations and the approach to math and science treat boys and girls equally. The Finns stress homework much less than in the U.S. schools. “I think meaningless math homework keeps girls in particular away from learning to love math. We have tried to develop a variety of teaching methods, including cooperative learning, problem-solving, concept attainment, role playing, and project-based learning,” says Sahlberg.

Paths to Math, a new math teaching and learning tool, which Sahlberg believes “fits very well in the educational environment where various methods of teaching are employed,” combines advanced pedagogical methods with the mobile learning environment. I caught up with the authors of the program, Maarit Rossi, Finnish math teacher and principal, and Cecilia Villabona, American math teacher and assistant principal, to find out more.

Adopting the Common Core Standards has meant a big change in how and when math is learned and taught in US public schools. How do you believe we can get better at teaching math?

Cecilia: The Common Core Standards (CCS) are guidelines defining the competencies students are expected to acquire in each grade level. In my opinion, they are creating a solid structure to encourage balance between conceptual understanding, procedural fluency, modeling with mathematics and creating student-centered classrooms. However, the danger of the CCS lies in the overemphasis placed on assessment, at the risk of pressuring teachers to “teach to the test”. In my opinion, the best curriculum and guidelines are no substitute for good classroom instruction by well-trained professionals using good materials.

Maarit: One important issue for the Finnish math teacher is to create a good atmosphere in the classroom. This means things like mutual respect and well-structured lessons to make sure that students learn and study together. We also think it is important to acknowledge different learning styles. Even though we have fewer math lessons each week than the average in European countries, we think it is very important to give students enough time to talk and think about the math. It helps them to build the conceptual understanding. When I was visiting here the first time in 2006 on my Fulbright, I noticed that some of the math books were huge. Who has time to make choices from all that material? I think that the content of math in the Core Curriculum has to build so that it allows teachers to have more time to make their choices and thus gives them the opportunity to teach math in more individual ways.

What do we need to do to encourage more American girls to embrace Math?

Maarit: I was positively surprised when we got the results of our school for PISA 2003. Girls got higher points than boys (Female 564/ Male563). Then I compared the results of Finland (Female 541/Male 548) to the results to all OECD participating countries (Female 494/Male 506). It seems that we are doing more equal gender math education than others. This gender comparison has continued to be similar in Finland when looking at the results of PISA 2006 and 2009.

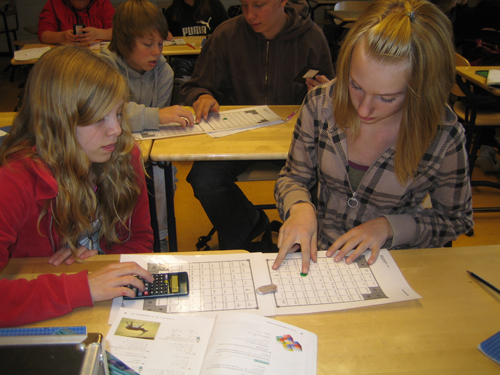

To get girls more involved and interested in math, it is good practice to use different teaching methods. Girls want to work in pairs and groups because they can test their thoughts and share their ideas about how to solve the math problems. Both girls and boys like to do hands-on exercises and move out from their chair. The key is to give girls more differentiated instructions.

What motivated you to create Paths to Math and in what ways does your product encompass all that you have learned as educators about successful math instruction for both girls and boys?

Maarit: In 1990, I visited Leeds University with a group of math teachers and professors. The university had done lot of research on learning. At that moment I understood that I was not able to transmit knowledge by showing math examples and asking students to repeat similar examples. The student has to build knowledge assisted by the teacher, who is leading to the right paths. We were a huge group of teachers changing our teaching from teacher-centered to student-centered. We noticed that we got good student motivation and learning results.

Paths to Math is based on long experience of math teaching and modern learning theory, updated with the new technology surroundings. The students of today, instead of repeating written tasks, can do motivating interactive tasks: game-like activities that give them supportive feedback. In Paths to Math there are also videos for students, which can be used individually to repeat or clarify a concept.

Cecilia: I visited Finland in 2006 on a Fulbright exchange. At the time, Finland was getting attention due to their high results in PISA. I had spent 25 years in the classroom as a mathematics teacher, mostly in the public high schools in Manhattan. When I looked at the material, I realized that during my most successful years in the classroom I had been creating lessons very similar to those materials.

As an Assistant Principal of Mathematics, I was in charge of teacher professional development. A challenge was to create time in teachers’ schedules for discussions about lessons and the needs of students, which at the time I did by working with the programmer and reducing the number of different preps for each teacher. I was pleasantly surprised to find out that this was part of the teachers’ day in Finland, and perhaps one of the reasons for its success.

I know there are many systemic differences that can’t be changed, but if teachers have good materials to save preparation time, they can devote more energy to interacting with students and to addressing their individual needs. That is why I became involved with the Paths To Math project.

What is the difference between your approach to teaching math and the approach historically taken in American public schools? What are the primary features of your program that make it more effective?

Cecilia: When making comparisons about teaching and learning, it is important not to over-generalize or place too much emphasis on any solution. Starting with the TIMSS report in 1995 (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study), the US started to look at the difference in students’ performance in international tests, and the possible reasons for it. I may hypothesize here, with no real data to prove it, that our overemphasis on standardized tests is rooted in these comparisons and in our zeal to ensure that our students rank at the top.

Studies done of Japanese, German and American mathematics classes started to show differences in pedagogy and methods used by teachers. One striking difference was that we taught for the answer and very quickly gave it to the students. As a classroom teacher, I believed that most learning happened during the struggle, and as I told my students often, they had to “love their mistakes because they were their learning opportunities.”

It is important as background to illustrate the differences in the approach of Paths to Math to teaching and learning. We believe that students need to develop self-confidence and trust in their ability to do math, and it is the solving of real-life, simpler problems that gives them the ability to engage in more difficult, abstract tasks. Only the procedural understanding acquired in this manner will empower students to solve the test problems. Paths to Math is not a test prep tool, although we have created pages of practice using test type questions. We feature more word problems, as well as opportunities for modeling research topics that relate to mathematics. We also provide tips for teachers to create a learning community by using individual, pair-share or group format, and suggest paths for differentiation of instruction. We advocate learning as a social activity, valuing the student interactions as part of the knowledge acquisition.

What kind of training is necessary for teachers to become capable of effectively using your program?

Cecilia: The interface for Paths to Math is teacher and student friendly. The material is organized into 10 modules, with clearly defined instructional targets. At the end of each module there is a summary page and a table of correlation to the Common Core Standards. This means that a teacher can look at these to plan, knowing what needs to be supplemented.

In a vibrant community of self-guided practitioners, within a well structured school, teachers using Paths to Math could develop their own professional groups to look at student work and analyze student needs; they could do a lesson study project and observe each other practice, or use their students results as formative assessment to decide on next steps needed for concept mastery.

In a less than ideal scenario, implementing Paths To Math in isolation would be hard. It is best done when others are also trying to have grounds for discussion and mutual support for changes.

For more information: www.pathstomath.com

All photos are courtesy of Paths to Math.

In The Global Search for Education, join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. Madhav Chavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finland), State Secretary Tapio Kosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Professor Ben Levin (Canada), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (Lycee Francais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today. The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland.

Recent Comments