“From the US Department of Education’s 2010 meta-analysis that showed that online learning was, on average, more effective than traditional face-to-face learning and that blended learning was the best of all, to the more recent RAND study of Carnegie Learning’s math program, increasing amounts of research are emerging to show its effectiveness.” — Michael Horn

Disrupting Class: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns (McGraw-Hill: 1st edition, May, 2008; 2nd edition, August, 2010) explored how technology might better serve future students.

The benefits of blended online and brick and mortar learning, such as individualization, universal access and equity, and productivity, sound powerfully tempting to policy makers looking for solutions to the failings of standardized education. Further, generations Y and Z have embraced online technology and show motivation to use it to learn. What then are the challenges in realizing the authors’ prediction that 50% of high school courses will be delivered online by 2019? Online learning is expected to improve with time but will it improve enough to offer students and parents value added that is greater than that provided by the traditional classroom? Does increased use of technology work for everyone? What about the socio-emotional aspect of learning?

I caught up with Michael Horn, author, co-founder of the Clayton Christensen Institute, and executive director of its education program, to discuss his latest thinking.

Online learning is a disruptive innovation relative to much of the electronic learning media that preceded it. Initially it was far more limited — because of bandwidth constraints, for example, its graphics were primitive. But online learning was often simpler to deploy than complicated server-based programs in schools or more affordable than computer-based options. As online learning has improved, as all disruptive innovations do, what distinguishes it from the prior electronic media is its interactive capabilities, both in terms of collecting data from how users interact with the software to improve — even in real time — as well as how it facilitates interactions between people — synchronously and asynchronously — in far more affordable and convenient fashion than Satellite ever made possible. Fundamentally, much of the electronic media that came before it was a one-way communication vehicle, which was highly limiting in terms of its ultimate impact, whereas online learning has far more transformational potential.

Do we have more evidence of the effectiveness of computer based learning 5 years on? What makes good online learning effective and what negatives should be noted?

More evidence is emerging. From the US Department of Education’s 2010 meta-analysis that showed that online learning was, on average, more effective than traditional face-to-face learning and that blended learning was the best of all to the more recent RAND study of Carnegie Learning’s math program, increasing amounts of research are emerging to show its effectiveness. But just as there are great online learning programs, there are also bad ones. What seems more clear is that just because something is online or blended, does not make it necessarily good or bad. Instead, effectiveness for each individual learner is far more determined by whether the program is driving the right instructional approach for each student at the right time based on the particular learning objective at hand. Online learning has unbelievable potential to help accomplish this personalization, but not all online programs do it. Indeed, the meta-analysis that showed that on average online learning is better, also showed that a key reason why is the increased time on task. Motivating students and personalizing for their needs seems critical.

How are teachers in conventional schools using technology more effectively 5 years on?

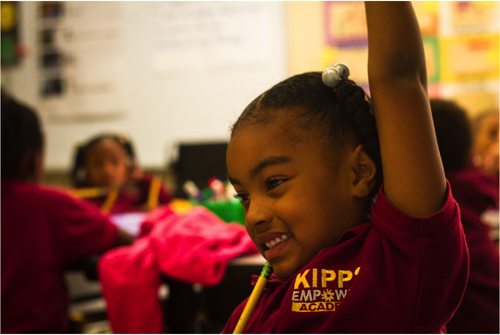

We’re seeing an increasing number of blended-learning schools that are great proof points for the power of personalization. Summit Public Schools in California, Rocketship Education, Carpe Diem, Mooresville Schools in North Carolina, Quakertown School District in Pennsylvania, and many more are doing some incredible work with blended learning. KIPP Empower in Los Angeles, CA, for example, moved to a blended learning model in August of 2010 to maintain its ability to do small-group instruction in the face of budget cuts that forced it to raise its class size to 28 students per class from its planned 20. 92 percent of its students qualified for the free-and-reduced lunch program, and at the beginning of the 2010-11 school year, only 9 percent were reading at a proficient of advanced level as measured by the STEP literacy assessment. These kindergarteners have now completed the second grade and have achieved some amazing things. California’s Academic Performance Index rates schools based on year-end standardized tests with 1000 being the highest score and 800 being the targeted score. KIPP Empower tested at 991.

Do you still believe 50% of high school courses will be delivered online by 2019? What evidence do you have to support this? How do you see this being realized?

I think we’ll be right plus or minus a few years on either side. It’s clear that online learning — in a variety of forms, from one-off courses, to full-time experiences, to an array of blended-learning programs — is still growing rapidly. Unfortunately sound data is very hard to come by, as few places track the growth in any comprehensive way to capture all the ways that online learning is growing.

Is there any research to show that some students are better suited to an online learning environment while others do better with face-to-face instruction (the student/teacher connection)?

There is research to show that certain students are not well suited to learn in a fully online environment, which tends to depend on their motivation, aptitude, and other such factors. Other students thrive in the experience, especially if they are self-starters. Some schools do a good job of figuring this out, but again, the ability to have an array of options — from full-time online programs to a variety of blended-learning options — seems really important to fulfill the ultimate promise of online learning, which is not to deliver a course online for the sake of the technology, but to design a schooling environment that is student-centered to be able to help students realize their fullest potential.

“The best blended environments also seem to create lots more opportunities for students to engage in project-based learning with other students, which can be a rewarding way to apply knowledge and learn skills and concepts far more deeply.” — Michael Horn

Online courses compete with brick and mortar schools for funding. Do you believe policy makers should be shifting more funding from brick and mortar to online or hybrid models going forward?

Course choice — in which funding follows students to the online course of their choice — is becoming an important option in several states. What’s exciting about it is the opportunity to help students who have limited options have access to any course that might meet their needs. Another thing that is potentially exciting about it is to create policies that tie the funding of these programs to actual student success and mastery of the course. That’s something that would be very difficult to do in a conventional school. As a result, giving students the option to have these experiences and to personalize their learning seems critical as does holding these new providers to a strict accountability, but top-down decisions about where to shift dollars probably does not make much sense. Creating the conditions for innovation around student-centered learning should be the ultimate priority, which means that if students would do best in a traditional experience, we shouldn’t deprive them of that either. Our sense is that as blended learning grows in schools, ultimately the online platforms that emerge underneath these experiences will help teachers work with students to find the right experience for them at the time they need it — whether that learning experience is online or offline.

Have you looked at the impact of brick and mortar socialization and direct person-to-person collaboration versus the online experience?

I think what we can summarize here is that each student has different needs based on his/her individual circumstance so different experiences work well for different students. Spending eight solid hours in front of a computer seems pretty clearly not an ideal way to learn, but I’m not aware of any full-time virtual schools that have students learn online all the time. Generally, families that have children in full-time virtual schools create lots of opportunities for students to have social opportunities with other adults and students. The results from one piece of research even suggest that typical, mainstream students enrolled in full-time, online public schools are in fact either superior to or not significantly different from students enrolled in traditional public schools with respect to their socialization. That said, because most families seem not to be able to create these types of experiences for their children, it’s a key reason why the future for most students will likely be in blended-learning environments that offer opportunities to learn online while also collaborating and socializing with other students. One of the things I’ve been most struck by when I enter blended-learning environments is the amount of positive social interaction taking place around learning, which is often a distinct contrast from the social activity I observe in traditional classrooms. Students in these blended environments are constantly popping up to head over to their neighbors and help them with any variety of learning questions and to ask questions of their own. The best blended environments also seem to create lots more opportunities for students to engage in project-based learning with other students, which can be a rewarding way to apply knowledge and learn skills and concepts far more deeply.

Photos are courtesy of Michael Horn and the Clayton Christensen Institute.

For more articles in the Got Tech? series: The Global Search for Education: Got Tech? – Finland, The Global Search for Education: Got Tech? – Canada, The Global Search for Education: Got Tech? – Australia, The Global Search for Education: Got Tech? – Singapore, The Global Search For Education: Got Tech? IB Schools in a Virtual World, The Global Search for Education: Got Tech? – Argentina.

In The Global Search for Education, join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. Madhav Chavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finland), State Secretary Tapio Kosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Professor Ben Levin (Canada), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (Lycee Francais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today. The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland.

Recent Comments