Poverty, ignorance, poor health and undernutrition trap the lives of mothers and infants in vicious cycles according to the findings of a Symposium on Maternal and Child Health and Nutrition in Emerging Markets that took place at Green Templeton College, University of Oxford earlier this year.

Every child should have an equal start in life. Yet millions of children in emerging markets do not. Preliminary results of a ground-breaking new multi-ethnic study, Intergrowth-21st, funded by the Gates Foundation, shows that fetal growth and development is determined more by the social, economic, nutrition and environmental condition of the mother before and during pregnancy rather than the mother’s nationality and ethnicity. The Intergrowth-21st findings inspire new insights into how governments, the private sector and civil society globally could level the health, growth, and development playing fields for infants and children from ethnic groups in all countries in the first 1000 days after conception.

Today in The Global Search for Education, we shall hear more about the issues and share some of the recommendations offered by the Symposium on Maternal and Child Health and Nutrition in Emerging Markets. It is my pleasure to welcome Sir George Alleyne (Chancellor, University of the West Indies), Tsung-Mei Cheng (Co-founder of the Princeton Conference), Caroline Fall (Professor, International Paediatric Epidemiology, University of Southampton, UK), Governor Madeleine Kunin (Author of The New Feminist Agenda, Defining the Next Revolution for Women, Work and Family), Sania Nishtar (Founder and President, Healthfile, Pakistan), and Srinath Reddy (President, Health Foundation of India).

Governor Kunin: Can you please summarize the new evidence about the critical importance of the first 1,000 days of life. What are the implications for poor and wealthy nations?

There have been dramatic reductions in maternal and infant mortality rates around the world. More lives can be saved if we can harness the research that informs us that the first thousand days of a baby’s life are critical to adult well being. Good nutrition and medical care for the mother play a crucial role long before fertilization takes place. No longer can we separate genetics from the environment because a mother’s genes may be influenced by malnutrition. The lessons we have learned tell us that the best investments a country can make are in good maternal and infant care. Not only will this save lives; it will help produce a society of healthy and productive adults.

Caroline Fall: We know what works for maternal and child health and nutrition (MCHN), and yet there is still a persistent failure of delivery. What are the factors involved?

Practically everyone in the world who has a surgical operation gets an effective anaesthetic. This is because anaesthesia is a relatively simple, brief, and direct treatment administered by a well-paid professional, and is of immediate obvious benefit to all concerned. Millions of mothers and children remain malnourished because ensuring good maternal nutrition and excellent pregnancy and child care is complex and takes concerted effort across multiple sectors and over many years. Maternal malnutrition creates few immediate problems, and policy makers may genuinely be ignorant of the far-reaching consequences of the stunting effects on the fetus and infant. They may genuinely be unaware that the child’s brain never makes up the deficit and that the child is destined to become a more sickly and unproductive adult. The main barriers are a lack of long-term vision and political will — the will to organise the food supply, to educate girls and women, and to build and maintain a skilled and motivated maternal and child health workforce.

Sania Nishtar: Is maternal and child malnutrition mainly a question of poverty and scarcity of food, poor availability of nutritional foods, or lack of education and poor choices? What is your view of the most effective ways to address the underlying issues?

It is a combination of all these factors, although the role played by financial access barriers is the most salient. The impact of factors such as poverty, maternal literacy, sanitation, and housing conditions on children’s health and, in turn, on social and economic outcomes, is well documented. The problem is that these factors are not amenable to isolated public-health interventions. But another, less widely discussed social determinant — maternal nutrition – could be. The good news is that there are solutions. Conditional cash transfers, text-message-based initiatives, school-based food programs, vitamin-fortification schemes, and local leadership have all proved effective in improving maternal nutrition. Such initiatives should be backed by policies that foster positive nutritional choices. Compelling policymakers to implement such policies will require a new set of skills that draws upon lessons from around the world. Initiatives aimed at enhancing the public’s knowledge of nutrition are also crucial — not least because they can motivate citizens to pressure their governments to take action.

Tsung-Mei Cheng: As an illustration of the MCHN crisis, what challenges must China address to make significant progress, and what strategies are they currently pursuing?

Maternal and child health and nutrition in China have been the major beneficiaries of China’s 1978 Reform and Opening. The reform ushered in a period of rapid economic growth of 10 percent a year for most of that period, particularly during 1990-2010. Between 1990 and 2010, infant mortality and under-five years mortality dropped by 70.5 percent and 69.8 percent, respectively, and the prevalence of underweight children by 50 percent. Maternal mortality dropped by 56 percent between 2000 and 2013, and 92 percent of all pregnant women received prenatal care.

Significantly, nine-year universal education during this period also vastly raised the ability of the Chinese “mother,” chief nurturer of the family, to properly care for her children. Challenges, however, remain. Rural Chinese children, especially those living in poorer inland and western provinces, still bear a disproportionate burden of growth-related problems. Stunting and underweight prevalence in central and western China is two to three times higher than richer eastern China. Rates of stunting and being underweight among the estimated 15 million children of China’s vast population of migrant workers who are left behind in the villages are one-and-a-half times those of their non-left-behind counterparts. Moreover, by the Chinese government’s own account, the infrastructure to improve rural child nutrition is still fragile, unstable, and vulnerable to changes in economic conditions. Also worrisome are the worsening trends in stunting and underweight prevalence since the 2008 financial crisis, and the toll that environmental pollution has taken and is continuing to take on all Chinese, including children who are more vulnerable to the harms that environmental degradation causes. Looking ahead, China’s slower economic growth today, and in the foreseeable future are likely to exacerbate the problems of Chinese children’s health and nutrition. Fortunately, China’s top policymakers are aware of the problems and have acted on them. For example, in 2011, China’s State Council issued the “Concise Outline of Child Development in China 2011-2020,” making improvement of maternal and child nutrition an important government mission and part of the 12th five-year plan. The specific goals are to reduce stunting, underweight and anemia prevalence among Chinese children. Some specific measures include strengthening health education and maintenance of women and children including teaching of knowledge about nutrition, and building comprehensive child nutrition monitoring programs. The Chinese government has decided to treat child nutrition improvement as a strategic mission in raising the quality of the Chinese people.

Sir George Alleyne: How do you see the progress with MCHN compared with progress in other basic human rights, such as literacy, and compared to the progress on major health problems, such as AIDS?

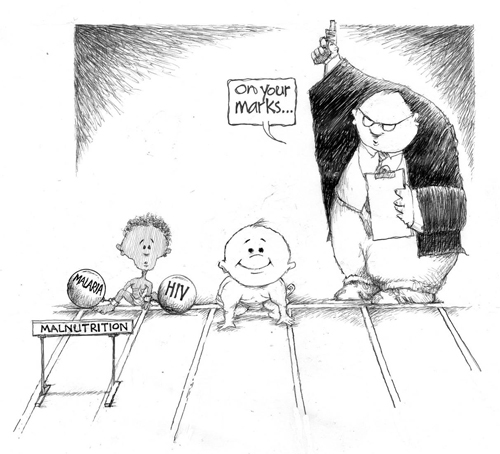

Recent years have seen remarkable progress in MCHN both in terms of the science of child growth and development, and in the programs and policies to be applied. There has been renewed and heightened interest in the past decade, partly because of the appreciation of the long term sequelae for health, education, the economy and social services of childhood malnutrition and stunting. There are technologies available for even more rapid advance if only the health services were adequate to deliver them effectively. The progress in this area has been as substantial as in the field of HIV, although the light of popular interest does not shine as brightly on the problems of mothers and children, which do not seem so dramatic.

Srinath Reddy: What are the largest MCHN challenges for India, and what strategies are most effective in your view?

Despite an accelerated rate of decline over the last decade, India’s aggregate national rates of maternal and infant mortality remain higher than those of her economic peers and even of several South Asian neighbors. The present rates (42 per 1000 live births for IMR and 178 per 100000 live births for MMR) fall short of the targets proposed in the Millennium Development Goals of 2000. Hidden within these numbers are huge inequities between different population groups, determined by region, income, education and caste. The high rates of maternal and neonatal mortality are partly responsive to the national program for increasing the demand for institutional deliveries. However, substantive impact can only be achieved if the quality of services provided in primary and secondary health care facilities is improved through a supply side response that provides skilled personnel, adequate infrastructure and assured availability of medicines. Efforts to reduce child mortality under 5 years must improve immunization coverage, sanitation, potable water supply, and primary care for acute respiratory infections and diarrheal diseases. Under-nutrition in childhood (an appalling 42percent) must be reduced not only to protect physical and cognitive growth but also to prevent susceptibility to both childhood infections and chronic diseases in later adulthood.

All Photos are courtesy of Green Templeton College, University of Oxford

In The Global Search for Education, join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. Madhav Chavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finland), State Secretary Tapio Kosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Professor Ben Levin (Canada), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (Lycee Francais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today.

The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland, is the publisher of CMRubinWorld, and is a Disruptor Foundation Fellow.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments