At public universities, it seems generally understood that anything communicated through the university email system is subject to inspection. The question posed today is: Did Harvard University, whose position on the question of privacy seems more ambiguous, make the right decision to secretly search the email accounts of 16 resident deans without first informing them? The Harvard investigators were looking for information related to a leak about the University’s cheating scandal in which about half the students in an undergraduate spring class called “Introduction to Congress” were thought to have been involved. As reported in the Boston Globe on March 10, the deans whose emails were searched were informed of Harvard’s actions on March 9, almost six months after the search took place. Was this an extraordinary circumstance in which Harvard University had no other option? Perhaps they concluded it was. Was there a better way to handle the execution given the respect due to Harvard’s esteemed academic community? From a legal and ethical perspective, what do people believe the right course of action should be for a trusted, honorable, private academic institution? I asked Howard Gardner, the John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and Alan Behr, a partner at the Phillips Nizer law firm and a member of its Corporate & Business Law Department and Intellectual Property Practice, to share their perspectives.

Please tell me the degree to which you think this privacy incident has concerned members of the Harvard community. What proportion of faculty and students of the University would you estimate share concerns for what has transpired?

Howard: To my surprise, I see a degree of mobilization that had not occurred with regard to the cheating episode. I am not sure why. Could be a cumulative effect, could also be that this hits closer to home. After all, it involves faculty and those that faculty considered colleagues – senior resident deans who were apparently treated differently from ladder or tenure faculty. Absent survey data, it is impossible to know the percentages in any constituency. I will say that a number of departments and cohorts have mobilized in ways that they did not before, but it is not yet clear how the mobilization will go and whether it will have any effect.

Do you believe there are any egregious acts that would give the right to an organization such as Harvard to access a faculty member’s or an individual’s private correspondence?

Howard: There are two separate questions. One has to do with the seriousness of the alleged transgression; the other has to do with whether the faculty member should be apprised before the fact. I think that the offense has to be serious (criminal or one that comes close to the heart of the educational enterprise, like scientific fraud) and the reason needs to be spelled out. Alan: Because the institution is accountable for what is on its servers, it has reason to say that it has the right to know what is on them. If the individual has something deeply private stored on the institution’s server, the first question is obvious: if it is so private, why did you upload it? If there is a dedicated electronic storage space for private files and it is so identified to the employee, the institution could have a tough time supporting any invasion of that space for almost any reason that is not listed within its information policy. If the private files contain information that is potentially related to a serious crime, the institution is perhaps on firmer ground in reading it than in most other serious situations.

On the question of privacy, do you think there should be any difference between an education that is privately paid for and an education that is publicly paid for?

Howard: At public universities, it is already understood that anything you write on your university email is subject to inspection, perhaps without notice. And so employees at such universities are forewarned. Those of us at private universities thought that a different set of rules applied; I certainly did. Note however that private education is also publicly paid for, not only by grants to students but also by its tax-free status, and so the once assumed privilege may gradually disappear. That cuts directly into the heart of the academic enterprise, which has assumed trust, privacy, community, and a moral basis.

Is there a distinction you would make between privacy protections and rights for a paid employee (such as a faculty member) versus a student who is paying customer of the university?

Alan: Very generally, you violate a person’s right of privacy when you obtain personal data on that person when he or she is in a situation in which it is reasonable to have an “expectation of privacy.” Someone taking pictures of you through your third-floor bedroom window while you are dressing for dinner is likely violating your right of privacy. If you stand in your bedroom window and shout to people on the street, however, what you say would not be considered private. The Duchess of Cambridge was seated outdoors when photographed topless – on the veranda of a private villa, and the photographer was said to be positioned far off, on a road. Does a famous person in a private space have an expectation of privacy when visible only with professional-grade optics from a considerable distance? Many believed so. Most institutions take the position that there is no expectation of privacy when communicating via their email systems. It is worth noting that they take different positions about telephones: you have a right to expect that your call is not being monitored or recorded. The distinction is based in part upon the fact that email is a permanent written record, one that could potentially subject the institution to liability. The institution should have a clearly articulated, publicized and readily accessible information systems policy in any event. Howard: I think that all members of a community should be equally protected. Interestingly, the Harvard administrator who defended the practice of looking at the mail of the resident deans said that the University did it to protect the privacy of the student. That argument did not work for me; in fact I think it is a specious argument designed to rally support from students and parents. I think it is equally important to protect the privacy of staff, faculty, and administrators. By the way, one faculty member pointed out that administrators should be considered staff and therefore should have their emails inspected. Needless to say, that provocative argument would not go well with administrators at Harvard or any other place.

From an ethical, and/or legal perspective, what do you believe is the right course of action for the Harvard administration to pursue following an incident such as this, to maintain both Harvard’s legacy as an academic leader and its integrity as a moral community?

Alan: The best thing to do is to have a clear, unambiguous information systems policy and to enforce it uniformly. You can make the rules different for faculty, students and administrative employees. Within each category, the policy should be evenly applied. It is all about transparency and fairness: if the policy says that a student’s emails are subject to being read, and the student emails his parents via his university account about how he cheated on an exam, he can’t complain if that email incriminates him. Howard: I agree absolutely with what Professor Rakesh Khurana of the Harvard Business School wrote to me. I quote here with his permission. “As an organizational behavior researcher, we teach cases like this over and over again. And yet, no matter how many times, people seem to repeat the same mistake. It seems that one of the simplest course of actions that would have ended this would have been a simple apology: “We were under a lot of pressure in a situation that we had no experience with. We made a judgment call. It seemed right at the time. In hindsight, it was wrong. We want to assure the community that something like this will not happen again.” Instead, what we got was the same hair-splitting and legalese that apparently the administration board detests when it hears from students–no sense of personal accountability; splitting hairs; hiding behind technicalities, etc.” More generally, after a genuine heartfelt apology along the lines suggested by Professor Khurana, I would say that the University needs to make it clear that it will follow a course that is much more respectful of the rights of all members of the community henceforth, and that it will try to embody in its actions what it means to be a trusting ethical community. Particular organizations, institutions, and professions do differ in the extent to which they embody trust, ethical behavior, a sense of community. As the best known and wealthiest university in the world, Harvard has a special responsibility to embody these virtues. Harvard’s reputation has deservedly been thrown into question by the events of the past year, as have the reputations of other schools that have experienced sexual harassment, ethical and racial slurs, drunken binges, misrepresentations to rating agencies, etc. Unless these institutions make extraordinary efforts to show that they are attempting to repair these injuries and to heal the community, they will lose the respect in which they were held for many years, and post-secondary education in the U.S. will be in jeopardy. How ironic it is that our liberal arts and science institutions have long been admired world wide, and yet they now could be undermined from within.

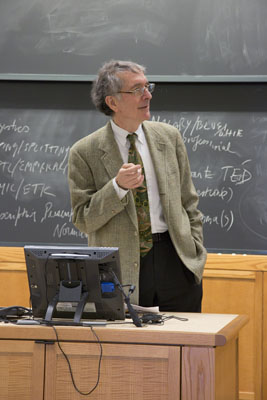

Photos courtesy of Harvard Graduate School of Education and Phillips Nizer LLC.

In The Global Search for Education, join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. Madhav Chavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finland), State Secretary Tapio Kosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Professor Ben Levin (Canada), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (Lycee Francais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today. The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland.

Recent Comments