Αυτο το μηνα, Το κοινό μπορεί να προβάλλει το αναγνωρισμένο ντοκιμαντέρ, Κλίμακα Ισλανδία (Επιμέλεια από NFFTY) επί το κανάλι YouTube του Planet Classroom Network.

Created by Adam Hersko-RonaTas, the film explores Iceland’s geological, biological and cultural history as well as the challenges and opportunities for this country’s rapid transition into a globalized world. Geophysicists, musicians, folklorists, fishermen, geneticists and children in a playground share their perspectives on the country’s past and its hopes for the future. Challenges include how to integrate foreign influences while preserving long standing traditions, the rights of immigrant workers and a fragile ecosystem.

Η Σφαιρική Αναζήτηση για Εκπαίδευση is pleased to welcome Adam Hersko-RonaTas.

What inspired you to create this film?

What inspired me to create this film was an attempt to combine my interest in art and science. I’ve always been inspired by the photographic work of Yann Arthus-Bertrand and his book, “Earth From Above”, which just captured my imagination with its imagery of the world ever since I was a kid. And then Mishka Kornai’s film, Growth, από 2015, explores the universality of growing up in different parts of the planet and the way that they filmed the subjects there solely from the sky above. So those are both direct sources of inspiration visually.

And then while I was studying neuroscience as an undergrad at Brown University, I recognized that the maps of the human genome are uncannily similar, visually, to the construction of Iceland’s road system, with Route One, this ring road that circumnavigates the island. And so in the same way this road map bridges these villages disbursed across expanses of uninhabitable landscape, the mapping of genomes also has all this uncharted territory between what are considered landmarks in the DNA sequence. And so this theme of proximity started to arise. And seeing it on two extremes from microscopic to macroscopic got me really excited about this analogy, even though I know it’s kind of a stretch. That wasn’t what I was resting on but was part of the spark. And then in my research, I just found it curious that Iceland is hailed as this fairly unique case study for human genetics because of the perceived homogeneity there; αν και, I learned that’s not entirely true. Because then also the results in these labs wouldn’t really be applicable elsewhere in the world.

But all that aside, I was curious to find more about the idiosyncrasies of this country that claim to be this sort of unique…or sort of form under these unique circumstances. And I found this research grant, called the Royce Fellowship, that I applied to for two years and then eventually was approved. And then I set out in the summer of 2017 to film this. I had been making films as a hobby for many years and thought it would be a satisfying creative challenge to bring what I had learned about cameras and editing to this research. And ultimately, the film became about much more. As I conducted these interviews, I found that I was interested in some more of the cultural and geological elements of this country beyond just the genetic. And that’s how it came together.

Do you believe the themes of your story will resonate with other countries facing similar challenges, π.χ.. balancing traditional ecosystems and cultures with the needs of a rapidly changing world? How can filmmakers help to shape perspectives?

I’d like to believe that the themes of this film resonate with other countries that are facing similar challenges in a more globalized world. So in the age of satellites, cell phones, the internet, and airplanes, the world is consistently melding closer and closer together. And this idea of proximity appears to become void. Και έτσι, because these vast oceans no longer serve as these obstacles for modes of communication and commerce and travel, it seems like actual space takes a back seat. But I think in reality our proximity to our kin, our neighborhoods, are where we still matter most of all. And there’s this richness, perhaps this feeling of involvement and engagement that comes with being rooted in a place. So this new, not that new, but this accelerated scramble of people and trends and resources across borders will throw any culture’s sense of security for a loop. And obviously, cultures have always been evolving but now they can do this so quickly that there will inevitably be parts of their ecosystem that gets left in the dust or stretched way thinner than its capacity, maybe because it hasn’t had the adequate time to catch up.

But with film as a medium, you can compress time and space as well. And that makes it possible for viewers to have this broader (but not necessarily always deeper, admittedly) view of the seemingly distant subject matter. I’d argue too that filmmakers have this moral responsibility to shape perspectives for the better, which can be interpreted in different ways. But I see that as a filmmaker working as an educator in a way by addressing or critiquing ways of being that audiences may not have been exposed to or simply take for granted, or as a guide. So demonstrating what’s possible if we’re able to take a good step back and actually sort of visualize our place on this earth.

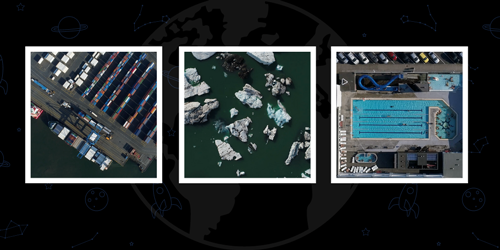

I noticed that many of the shots are drone shots from varying altitudes depending on the subject presented on screen. What influence do you think this had over Iceland’s depiction in your film versus filming the country from the ground?

I find it incredible that our knowledge of the planet and ourselves has constantly been shifting with tools like hot air balloons and microscopes, now drones that have sort of enabled us to see the world from previously unseen angles. And the microscope offered this top-down view of this tiny world, invisible to us for so long. Now that we’ve crafted this window into the smallest cellular landscapes and views of the largest mountainous landscapes, we have this new way of piecing together spatial relationships between natural elements and how they ultimately affect the bigger picture. So my hope with using a literal top-down perspective by filming with a drone in this project was to grant the illusion of looking at a country through a microscope of sorts. And it was to compare these patterns of proximity on these various scales. So the micro being in reference to genetic, human-scale being in reference to culture, and then macroscopic scale being in reference to these larger geological structures.

And I realized this might actually kinda create a sense of removal; αλλά, that distance was on purpose. And I’m not as interested in the convention of talking heads in documentaries. So my instinct was that by avoiding faces altogether, the information wouldn’t be tied to any specific identity and the themes perhaps more universally applicable. I also wanted to let the interviewees’ voices do all the heavy lifting. Though this was all sort of an experiment editing, I wasn’t sure it would succeed but I’ll have to let audiences be the judge of its effectiveness. I figured that filming down from the ground would have provided a more familiar perspective, so by pulling away, I hoped it would provide a more objective viewpoint on these patterns that are united across levels of scale. And that would hopefully remind us that there’s this inescapable interconnectedness between everything.

What changes do you predict will occur to Iceland’s land and society in the future?

Admittedly, I’m not sure if I have a particularly hot take on what will happen to Iceland in the future. Though based on what people in Iceland expressed to me, my prediction of what will happen to the land physically is that it will continue to rise from the ocean, especially as glaciers continue to melt and the natural wonders will be further eroded under the footsteps of tourists if the influx of visitors continues at the pace it has. And then of course, there’s always the threat of a spontaneous volcanic eruption. But that risk seems to be sort of a part of the culture there. They even see it as a form of entertainment. But of course, the geothermal energy that it provides powers the entire country too. Icelanders are very conscientious of their natural resources so I can’t imagine they’re racing to over-develop the landscape anytime soon. They also depend on a lot of open land for grazing their main source of meat, which is sheep. So I hope they manage to keep the landscape as open as they have for the health of the currently thriving ecosystem.

And then societally, my guess is as good as any. I mean, I think they’re very committed to maintaining their folklore. And especially their language which hasn’t actually changed in 1000+ χρόνια. So they’re very committed to keeping up certain traditions already, so I can’t imagine that will disappear; and then of course they’re very selective about the commercial influences they allow to set up shop within their borders. So I think even in the wake of globalization and this extreme blending of cultures elsewhere in the world, they might remain the least changed for some time. But of course, some outside influence is inevitable.

What do you hope audiences take away from this film?

I hope audiences are inspired by this film to consider broader perspectives on cultural, biological, and geological patterns that they see wherever they call home. I also hope they come away with a sense of awe and appreciation for nature, and have a sobering reminder that we strive as a species to retrofit this environment to our needs even in the most extreme conditions.

The landscapes at every level ultimately shape who we become, and also that no system is a fully closed system. Even a place as seemingly isolated as Iceland has always been influenced by the reaching effects of life elsewhere on this planet.

Thank you Adam.

Ο.Μ.. Rubin and Adam Hersko-RonaTas

Don’t Miss the acclaimed documentary, Κλίμακα Ισλανδία (Επιμέλεια από NFFTY) επί το κανάλι YouTube του Planet Classroom Network.

Πρόσφατα σχόλια