John Ruskin was probably the greatest British critic of art, culture and society of the nineteenth century, in addition to being an educator. He believed that art and the development of imagination were profoundly important to an individual’s education. Ruskin was Oxford University’s first Slade Professor of Fine Art. I recently had the pleasure to connect with Professor Robert Hewison after reading his illuminating book, Ruskin and Oxford: The Art of Education. “Ruskin believed that everyone had visual as well as verbal capacities that needed to be developed in order to become a complete human being, and that the apprehension of truth depended on the power of observation,” explained Hewison. “His concern for art education applied to the development of the power of the hand and eye for everyone, not just people who hoped to become professional artists.”

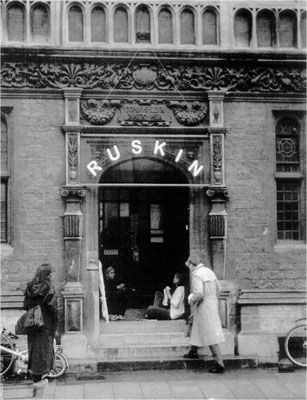

My curiosity to discover more about John Ruskin’s legacy found me outside the great doors of the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art on Oxford’s High Street. Would Ruskin recognize all the practices that went on there today, Mi chiedevo? I had the pleasure of discussing this with Dr. Jason Gaiger, Head of the school today and a Fellow of St Edmund Hall, Oxford.

Jason, would you say John Ruskin’s legacy is evident in the Ruskin School today?

Ruskin’s legacy is not evident in the way that is sometimes thought. He has the historical status of being a great Victorian figure, so people sometimes think that the School is a very traditional center of painting and drawing techniques. Infatti, it is a contemporary art school. Students here study everything from installation, performance, and video art to the latest multi-media technology. But they also have a strong grounding in traditional art skills. One of the things that makes the Ruskin distinctive is that it is now the only art school in the country where students still draw from the cadaver, made possible through the close connection with the School of Pathology here at the University of Oxford. There are also life-drawing classes that are open to the students and to other members of the University.

Where does the school fit in under the larger University of Oxford umbrella?

The School was founded in 1871 and was originally housed in what is now the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archeology. The students at that time would draw from the casts and the sculptures there. For a long while, the School was not, perhaps, central to the main concerns of the University and it didn’t have degree awarding powers. In 1974, it moved from the Ashmolean to the current site on the High Street. In 1977 it was fully incorporated and the degree course was introduced, becoming a classified BFA honours degree in 1991. Equally importantly perhaps, all the students now have a college association. That means although they study here at the Ruskin, they also belong to one of the colleges, whether it be Christ Church or St. Edmund Hall or one of the others. Students here are being trained to be artists. Tuttavia, because they are studying at the University of Oxford, their experience is different from that of students at some of the London art schools who can sometimes be trapped in a fine-art bubble where they only encounter other art students. Our students share college facilities with people who are studying a range of subjects across the University. Art is as much about ideas as it is about physical materials, and here at Oxford, students have direct access to a treasure house of ideas. The University is an incredible source of knowledge that artists can draw on and allow to feed into their art practice.

What are your thoughts on the amount of focus given to the arts in K through 12 in the UK?

What we find during the admissions process is that students who come straight from A level (secondary school) aren’t always ready to study art at degree level. A school education is not usually enough and students generally need to do a foundation course after secondary school to bring them to the appropriate level. There may be a few exceptions of incredibly gifted students or students who have received unusually good support in the secondary school they have come from. An underlying question here is whether visual intelligence is valued in the same way as verbal intelligence in secondary schools. The Ruskin is perhaps unusual in that, as well as a strong portfolio, students need to get the same high A level grades as for any other academic subject at Oxford; the same criteria apply whether you want to study fine art, medicine or law. At the Ruskin, 25% of the BFA degree is in the history and theory of art, which means that a substantial part of the program is academic as traditionally conceived. We tend to attract students who are both verbally and visually gifted. But in the portfolio we’re really looking for potential. I think that’s where we feel we are not given the support we would like from secondary schools. Fine art teaching in secondary schools often takes the form of set projects. All the pupils in a class are given the same specified tasks to complete with the result that the work they produce ends up looking rather similar. In altre parole, gli studenti’ individuality has not been fully developed. Per questo motivo, we always interview candidates and ask the students to talk to us about the work they have produced.

What do you believe the role of the arts should be in education today?

It troubles me when the arts are treated as something supplementary or merely ancillary to the university’s core activities. My own view is that the arts are just as intellectually rigorous, just as demanding and just as exacting in their standards of excellence as any other field of learning. The students here at the Ruskin don’t feel they have any less standing than their peers working in other subject areas. Come ho già detto, there is a substantial academic component to the BFA degree involving the study of art history and theory, but the studio-based component of the degree has its own intellectual value. Art does not have to rest upon the traditional methods of academic learning in order to justify itself as an independent mode of enquiry. Perhaps the appropriate comparisons are not to be made with other humanities subjects. The sorts of activities that take place in the studio are quite dissimilar to the largely text-based research that takes place in the history faculty, per esempio. But there may be points of commonality with the forms of research that take place in science labs or among mathematicians. We need to recognize that there are many different forms of rigorous intellectual enquiry (like studio art) that don’t involve sitting down and writing essays.

One of the leading education systems in the world — Finlandia — is planning to increase the number of hours allocated to the arts in secondary education. Does that surprise you?

It doesn’t surprise me. There is a difference, naturalmente, between the attempt to develop a more holistic approach to educational development at school level and the inevitable degree of specialization that takes place at university. By the time students come to Oxford, they have already elected to study a particular subject. Tuttavia, we encourage students not to isolate themselves in a specific discipline. One of the advantages of the collegiate system is that it allows students to make connections across disciplinary boundaries and thus to acquire a much broader sense of what constitutes knowledge. I strongly endorse providing greater support for the arts at school level. Drawing and painting are not just about producing beautiful objects. They are also about learning to look, and to learn to look is to learn to understand.

Technology has changed the arts enormously. How do you view the benefits and the challenges of this change?

Here at the Ruskin there used to be a large print making department. It was a slow, rather time-consuming process and the equipment took up a lot of space. Today that process has been replaced in part by the use of computer imagery and digital software such as Photoshop, though print making still remains. There is an element of organic evolution in this. New technology is definitely on the rise and students are of course interested in the possibilities it opens up. Tuttavia, you still have to learn how to use the technology and even then the technology is not going to do the work for you. We encourage students to acquire the necessary skills to enable them to do what they want, but without becoming slavishly dependent on acquiring skills that aren’t deployed for some purpose. The world is full of people who are technically accomplished but this doesn’t suffice to turn them into artists. Ciò nonostante, technical skills are indispensible. Lasciate che vi faccia un esempio. Someone may have the most wonderful ideas for building a large-scale sculpture, but unless she has learned how to construct it properly, perhaps through making a maquette, she does not yet know whether it will be sufficiently stable to carry its own weight.

For more information about the Ruskin School

Photos courtesy of the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art.

Nel Global Search per l'Educazione, unirsi a me e leader di pensiero di fama mondiale tra cui Sir Michael Barber (Regno Unito), Dr. Michael Block (Stati Uniti), Dr. Leon Botstein (Stati Uniti), Il professor Argilla Christensen (Stati Uniti), Dr. Linda di Darling-Hammond (Stati Uniti), Dr. Madhav Chavan (India), Il professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Il professor Howard Gardner (Stati Uniti), Il professor Yvonne Hellman (Paesi Bassi), Il professor Kristin Helstad (Norvegia), Jean Hendrickson (Stati Uniti), Il professor Rose Hipkins (Nuova Zelanda), Il professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Sig.ra. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgio), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finlandia), Segretario di Stato Tapio Kosunen (Finlandia), Il professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgio), Il professor Hugh Lauder (Regno Unito), Il professor Ben Levin (Canada), Il professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Il professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. PAK NG (Singapore), Dr. Denise Papa (Stati Uniti), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (Stati Uniti), Sir Ken Robinson (Regno Unito), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finlandia), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OCSE), Dr. Anthony Seldon (Regno Unito), Dr. David Shaffer (Stati Uniti), Dr. Kirsten Immersive Are (Norvegia), Cancelliere Stephen Spahn (Stati Uniti), Yves Theze (French Lycee US), Il professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Il professor Tony Wagner (Stati Uniti), Sir David Watson (Regno Unito), Professor Dylan Wiliam (Regno Unito), Dr. Mark Wormald (Regno Unito), Il professor Theo Wubbels (Paesi Bassi), Il professor Michael Young (Regno Unito), e il professor Zhang Minxuan (Porcellana) mentre esplorano le grandi questioni educative immagine che tutte le nazioni devono affrontare oggi. Il Global Ricerca per l'Educazione della Comunità Pagina

C. M. Rubin è l'autore di due ampiamente lettura serie on-line per il quale ha ricevuto una 2011 Premio Upton Sinclair, “Il Global Ricerca per l'Educazione” e “Come faremo a Leggere?” Lei è anche l'autore di tre libri bestseller, Compreso The Real Alice in Wonderland.

Segui C. M. Rubin su Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Commenti recenti