“The policy-driven reforms have focused largely on outputs, d.h.. achievements on test scores, without the same attention given to the sufficiency of inputs (adequate resources, especially in poor schools) and the quality of throughputs (the educational process itself).” – Jonathan Jansen

“I hold a Bachelor’s Degree in Arts…” – Nelson Mandela

Those were the words Nelson Mandela used in 1964 to open his 10,699 word defense in the historic Rivonia Trial. “It expresses both an achievement and an ideal worth striving for,” explains today’s contributor to Die globale Suche nach Bildung, Jonathan Jansen, Vice-Chancellor and Rector of the University of the Free State in central South Africa, President of the South African Institute of Race Relations, and a Fellow of the Academy of Science of the Developing World. In that year, nur 298 Africans passed “matric” with university entrance, and in this society with a turbulent racial past, nur 98 had been awarded bachelor’s degrees in the previous year. “Auch heute noch,” continues Jansen, “holding a first degree would distinguish a young South African from disadvantaged communities; in the 1960s, such an achievement would have been stupendous.”

Wie Sie heute in Teil entdecken 2 von der “Bildung ist mein Recht” Serie, Mandela’s education legacy continues. Equity-focused educational change is Jonathan Jansen’s work. He seeks to turn around some of the most dysfunctional schools in rural South Africa, using a strong mentorship-based model of change. Zusätzlich, Helen Janc Malone, whose new book Führende Bildungs ändern: Globale Fragen, Herausforderungen, und Lektionen auf dem gesamten System Reform features Jansen’s work, weighs in. Helen is Director of Institutional Advancement at the Institute for Educational Leadership in Washington DC.

Why didn’t Mandela’s government force integration in all schools once they came into power?

South Africa had a negotiated political settlement, which in spirit and content preempted any radical reform of economy, society and education. The Constitution enshrined the rights of all South Africans, such as language rights, and the new Schools Act legislation ceded considerable power to school governing bodies -Black and White – to determine things like the language policy and enrollment levels of a school, provided of course there was no discrimination. Außerdem, the new government wanted to ensure a strong public school sector and feared that any strong intervention in former White schools would cause these middle class communities to establish their own private institutions. In any event, many (though not all) White schools had allowed for gradual racial integration without reaching that tipping point where Black student numbers grew to the point of causing White flight. Where that happened, all White schools became all Black schools almost overnight. White Afrikaans schools, often the most conservative of all types of White schools, would often remain dominant White using language rights (Afrikaans) as a shield to defend the status quo. Rural White Afrikaans schools, often with poor students and empty classrooms, came under huge pressure to admit Black students from overcrowded township schools; in many cases, this led to parallel English classes for Black students, not without racial conflict in many cases. Insgesamt, the march to racial integration in all schools continues, and it is simply a matter of time, given the overwhelmingly large Black student numbers, that all schools will be racially integrated without the need for too much political pressure.

“You need a government that is deeply committed to educational reform beyond simply increasing the levels of funding to schools.” – Jonathan Jansen

What types of public schools currently exist in South Africa?

The first major differentiator of public schools is race. Mehr als 80% of schools are exclusively Black given the demographics and history of South Africa; this is unlikely to change given White racial consciousness and set patterns of residential segregation. The only changes to be expected will continue to be in the minority of White schools where racial integration has been uneven but will, in time, result in Black majority schools as well. The second differentiator is class. Über 20% der südafrikanischen Schulen sind Mittelklasse Weiß Schulen mit mehr Rassenintegration in den ehemaligen Weiß Englisch Schulen und weniger in Weiß Afrikaans Schulen. Mittelklasse Schulen haben mehr und mehr von ihrer Schule Mittel aus Mutter Beiträge als staatliche Finanzierung dieser öffentlichen Schulen zurückgegangen angehoben. Die wohlhabenderen Weiß öffentlichen Schulen sind vor allem Englisch mit einer kleineren Anzahl von Black Studenten angesichts der exorbitanten Schulgebühren, die die meisten Schwarzen Studenten auszuschließen. Black schools are further subdivided by government according to five “quintiles,” which reflect different levels of socio-economic need, with the poorest schools receiving more state funding than the rest.

What is being done to create excellent schools for all in South African children?

The primary instrument for governmental action in the post-apartheid period has been state policy. The plethora of policies has been largely symbolic, powerful statements of anti-apartheid values admired for profound and progressive pronunciations about a better society. In der Praxis, there has been a considerable distance between policy and practice for the following reasons: low levels of capacity for implementation; high levels of corruption such as in the woefully inadequate textbook delivery system; weak accountability systems for teachers; and a strong teachers union, allied to the ruling party, which consistently blocks any fundamental reforms of education that makes any stringent demands on teachers.

Dann, the policy-driven reforms have focused largely on outputs, d.h.. achievements on test scores, without the same attention given to the sufficiency of inputs (adequate resources, especially in poor schools) and the quality of throughputs (the educational process itself).

Schließlich, reform interventions at the school level, such as new curricula, consistently underestimate the levels of dysfunction in township schools (few schools have a predictable timetable) and the low levels of subject matter competence among teachers.

The most successful interventions to reform schools happen outside of government through non-governmental organizations, religious organizations, the private sector such as large banks and accounting firms, und Universitäten. Most of these interventions focus on improvements in physical science and mathematics education, and there is demonstrable evidence that without the impacts of these non-state initiatives, the achievements of poor township schools would be even more disastrous.

The limitations of such non-state initiatives are their limited system-wide impacts on 29,000 Schulen; for that you need a government that is deeply committed to educational reform beyond simply increasing the levels of funding to schools.

“The challenges facing the South African public education system underscore the need to approach educational change in a comprehensive, rather than a piecemeal way – one that pays equal attention to inputs, throughputs, and outputs; that encourages public-private partnerships and school-community relationships, and focuses attention on improving the teaching force.” – Helen Janc Malone

Helen, what can we learn from South Africa’s system level change?

Racial integration in education is a gradual endeavor in societies with turbulent racial pasts. The public policy call for social cohesion, integration and democracy is not often matched in practice, where tensions, divisions and challenges remain, particularly in communities that feel disenfranchised or threatened by the aspiring social goals. Racial and socio-economic stratification persists in one form or another and continues to undermine the opportunities for all children to receive quality education.

The challenges facing the South African public education system underscore the need to approach educational change in a comprehensive, rather than a piecemeal way – one that pays equal attention to inputs, throughputs, and outputs; that encourages public-private partnerships and school-community relationships, and focuses attention on improving the teaching force. Access to and quality of learning opportunity, particularly for Black students from lower and middle classes, muss im Mittelpunkt der Bildungsreform sein, wenn Schüler sind, um eine Chance zu gedeihen und zu erleben sozialen Aufstieg haben. Dies ist nicht nur eine Frage der Eigenkapital; es entscheidend für die Demokratie und den Wohlstand des Landes als Ganzes.

Die Herausforderungen und Chancen in Südafrika präsentieren anschaulichen Überlegungen für die Weltgemeinschaft. Wie vielen Gesellschaften immer Plural und / oder Kampf von Barrieren und Schichtungen, die sozialen Wohlstand und Fortschritt erstickt weg, educational change necessitates fresh approaches that lift up all students and, insbesondere, the traditionally marginalized, using education as a vehicle for positive social change.

Helen Janc Malone, C.M. Rubin, Jonathan Jansen

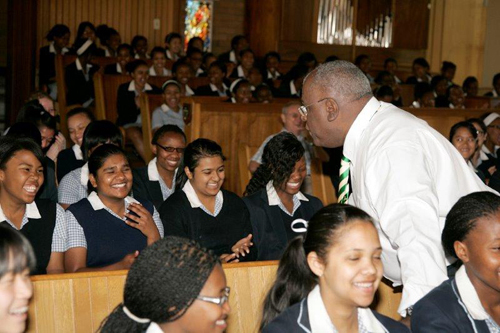

Photos are courtesy of the University of the Free State.

To read more about Jansen’s and Malone’s work on equity, sehen Führende Bildungs ändern: Globale Fragen, Herausforderungen, und Lektionen auf dem gesamten System Reform (Teachers College Press, 2013) bei http://store.tcpress.com/0807754730.shtml

Weitere Artikel in der Bildung ist mein Recht Serie: Die globale Suche nach Bildung: Bildung ist mein Recht – Indien, Die globale Suche nach Bildung: Bildung ist mein Recht – Mexiko, Die globale Suche nach Bildung: Bildung ist mein Recht – Brasilien, Die globale Suche nach Bildung: Bildung ist mein Recht – Großbritannien

In der globalen Suche nach Bildung, mit mir und weltweit renommierten Vordenkern wie Sir Michael Barber (Vereinigtes Königreich), DR. Michael Block (US-), DR. Leon Botstein (US-), Professor Ton Christensen (US-), DR. Linda Hammond-Liebling (US-), DR. Madhav Chavan (Indien), Professor Michael Fullan (Kanada), Professor Howard Gardner (US-), Professor Andy Hargreaves (US-), Professor Yvonne Hellman (Niederlande), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norwegen), Jean Hendrickson (US-), Professor Rose Hipkins (Neuseeland), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Kanada), Herr Jeff Johnson (Kanada), Frau. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgien), DR. Eija Kauppinen (Finnland), Staatssekretär Tapio Kosunen (Finnland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgien), Professor Hugh Lauder (Vereinigtes Königreich), Professor Ben Levin (Kanada), Herr Ken Macdonald (Vereinigtes Königreich), Professor Barry McGaw (Australien), Shiv Nadar (Indien), Professor R. Natarajan (Indien), DR. PAK NG (Singapur), DR. Denise Papst (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (Indien), DR. Diane Ravitch (US-), Richard Wilson Riley (US-), Sir Ken Robinson (Vereinigtes Königreich), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finnland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), DR. Anthony Seldon (Vereinigtes Königreich), DR. David Shaffer (US-), DR. Kirsten Sivesind (Norwegen), Kanzler Stephen Spahn (US-), Yves Theze (Lycee Francais US-), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Kanada), Professor Tony Wagner (US-), Sir David Watson (Vereinigtes Königreich), Professor Dylan Wiliam (Vereinigtes Königreich), DR. Mark Wormald (Vereinigtes Königreich), Professor Theo Wubbels (Niederlande), Professor Michael Young (Vereinigtes Königreich), und Professor Zhang Minxuan (China) wie sie das große Bild Bildung Fragen, die alle Nationen heute konfrontiert erkunden. Die Global Search for Education Community-Seite

C. M. Rubin ist der Autor von zwei weit Lese Online-Serie für den sie eine 2011 Upton Sinclair Auszeichnung, “Die globale Suche nach Bildung” und “Wie werden wir gelesen?” Sie ist auch der Autor von drei Bestseller-Bücher, Inklusive The Real Alice im Wunderland.

Jüngste Kommentare