“Education systems have untapped potential to improve themselves.” – Mel Ainscow

Equity-focused educational change is probably the most discussed, debated and urgent problem we face in U.S. education today, particularly as poverty continues to grow. The term “closing the achievement gap” refers to decreasing the disparities in academic results between Black and White, Latino and White, and recent immigrant and White students. There are those who believe there is too much focus on accountability. There are those who believe the achievement gap is not created by schools. More and more studies confirm that children who are born disadvantaged to parents who have no education do poorly in testing programs compared to children who grow up in affluent families and begin life with many more advantages. Other studies have found startling inequities between schools serving poor students versus those serving the affluent. Does providing poor schools with additional resources substantially improve student success, or does one also have to simultaneously address the issues related to family economic well-being? If we want to achieve the levels of the highest achieving countries around the world, we need to embrace the vision that an excellent education is the right of every single child. Now is the time to pull together our best research, knowledge and skills, and improve the educational experiences of low-income and racial minority students. I was delighted to discover that Helen Janc Malone chose to focus on achieving equity in education in her new book, Leading Education Change: Global Issues, Challenges and Lessons on Whole System Reform.

Today in The Global Search for Education, I begin a new series on this topic with Helen and four of her global authors whose work is focused on educational change. First up is Mel Ainscow, professor of education and co-director of the Centre for Equity in Education at the University of Manchester in the UK. Mel’s work focuses on inclusion, teacher development and school improvement. Helen Janc Malone is Director of Institutional Advancement at the Institute for Educational Leadership in Washington DC.

Mel, what factors do you believe play a role in student learning in low income communities?

We know that children with low attainment tend to come from poorer families. These families often live in deprived urban areas, where there are high levels of poor housing, unemployment, ill-health and a host of other factors associated with poor educational outcomes.

We also know that neighborhood dynamics are important: the type of school the students attend, the mix of students, and their experiences in the school are also important. This suggests that school and non-school factors combine to lower the attainment of children and young people who are already disadvantaged by their backgrounds.

“School partnerships are the most powerful means of fostering improvements, particularly in challenging circumstances.” – Mel Ainscow

Please briefly summarize the goals and achievements of the Greater Manchester Challenge.

Between 2007 and 2011, I led an initiative that set out to address this important policy agenda in more than 1,100 English schools. Known as the Greater Manchester Challenge, the project had a government investment of around £50 million ($80 million). The decision to invest such a large budget reflected a concern regarding educational standards, particularly amongst young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. After three years, the impact was significant in respect to improvements in test scores and indeed, the way the education system carries out its business.

Four important lessons emerged that have implications for developments elsewhere. Lesson one is that education systems have untapped potential to improve themselves. Consequently, the starting point must be with a contextual analysis. In Greater Manchester, this convinced us that most of the expertise needed to take the system forward was there within our schools. Our aim therefore was to move knowledge around.

This conclusion led to the second lesson, that school partnerships are the most powerful means of fostering improvements, particularly in challenging circumstances. Focusing on 200 or so schools that we designated as the “keys to success,” each carried out its own analysis of need with the support of a team of expert advisers. They were then partnered with another school that was known to have relevant strengths.

It is significant that such partnerships often had a positive impact on the learning of students in both of the schools. This is an important finding in that it draws attention to a way of strengthening relatively low performing schools that can, at the same time, help to foster wider improvements in the system. It also offers a convincing argument as to why a relatively strong school should support other schools. Put simply, the evidence is that by helping others you help yourself.

The third lesson is that networking is a means of stimulating experimentation with new ways of working. However, pathways have to be created that cross the social boundaries that prevent the movement of ideas within the system. With this in mind, we created “families of schools,” using a data system that grouped schools from different neighborhoods on the basis of the prior attainment of their students and their socio-economic home backgrounds.

Led by school principals, the families proved to be successful in strengthening collaborative processes, although the involvement of schools remained uneven and there were concerns that too often those that might most benefit chose not to do so.

The fourth lesson is that the leadership has to come from within schools. The good news is that we found that many successful principals were motivated to take on system leadership roles.

These four lessons provide the basis for developing self-improving school systems. However, such developments do not happen by chance. They require national policies that help to create the conditions within which locally led action can be taken. They also require some form of coordination at the district level.

“Leadership has to come from within schools.” – Mel Ainscow

What can we learn from the Harlem Children’s Zone experiment and what is transferable to other high risk school zones?

Within the international research community, there is a division of opinion regarding how to improve outcomes for disadvantaged students. On the one hand, there are those who argue that what is required is a school-focused approach, with better implementation of the knowledge base from school effectiveness and improvement research. On the other hand, there are those who argue that such school-focused approaches can never address fundamental inequalities in societies that make it difficult for some young people to break with the restrictions imposed on them by their home circumstances.

An obvious possibility is to combine the two perspectives by adopting strategies that seek to link attempts to change the internal conditions of schools with efforts to improve local areas. This is a feature of the highly acclaimed Harlem Children’s Zone, a neighborhood-based system in New York. What is important about the approach is that it is doubly holistic. Firstly, it links attempts to improve schools with efforts to tackle family and community issues that make it difficult for children to do well. Secondly, it sustains these efforts by providing “cradle-to-career” support as the child grows into an adult.

Helen, what can we learn from the Greater Manchester Challenge?

The old adage that “schools can and should do it alone” is a myth debunked by a burgeoning body of research that shows that partnerships, relationships, collaboration and knowledge sharing matter in improving instruction, changing school cultures and positively impacting students’ lives. While schools by themselves cannot offer solutions to all the social ills that burden the lives of students, meaningful partnerships between and across schools can help to create conditions and opportunities that promote learning and positive development. We see this in the Harlem Children’s Zone in the U.S. context and we see that in the Greater Manchester Challenge in the UK.

What Ainscow’s illuminating work indicates is that there is much to be hopeful about when it comes to educational change. Collaboration among schools can be a powerful tool for innovation, improvement and individual and institutional learning. Building an educational culture that encourages within and across school sharing of promising practices, continuous professional development and staff empowerment leads to a motivated and inspired staff fully engaged in knowledge generation, development and sharing in direct service to improve the lives and academic outcomes of all students. Opening doors to school-community partnerships helps schools focus on their goals while ensuring that students have access to robust, high-quality services and programs that complement their school experience. Schools are a central institution in most communities and as such, have a critical role to play in addressing equity of learning opportunity. The Greater Manchester Challenge offers an example of how substantive partnerships can help schools improve and students achieve.

For more information on Ainscow’s and Malone’s work on equity, see Leading Educational Change: Global Issues, Challenges, and Lessons on Whole-System Reform (Teachers College Press, 2013) at http://store.tcpress.com/0807754730.shtml

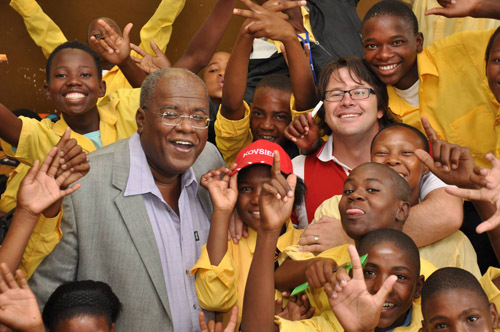

Helen Malone, C.M. Rubin, Mel Ainscow

Photos courtesy of Mel Ainscow.

For more articles in the Education Is My Right series: The Global Search For Education: Education Is My Right – India, The Global Search For Education: Education Is My Right – Mexico, The Global Search For Education: Education Is My Right – Brazil, The Global Search For Education: Education Is My Right – South Africa

In The Global Search for Education, join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. Madhav Chavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finland), State Secretary Tapio Kosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Professor Ben Levin (Canada), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (Lycee Francais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today. The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments