The technology revolution continues to play a significant role in making it easier for students to think internationally in terms of their higher education options. The Internet has made it simpler for students to research and apply to universities. Interviews can be done by Skype. At a time when President Obama has raised awareness for the rise in U.S. college costs, American students are increasingly thinking international and seeking their degrees across the pond (in England) according to HESA. Not only are there in many cases savings to be made in tuition fees, the top UK universities rival the best American ones in terms of prestige (see Times Higher Education World University Rankings and U.S. News World’s Best Universities Rankings). Putting aside finances and rankings, what price would you put on the cultural experience of studying in one of the oldest and most famous universities in the world?

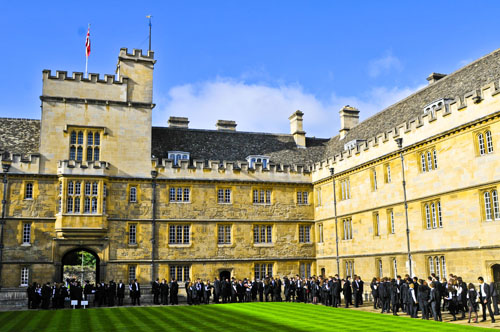

“Architecture aims at Eternity,” said Sir Christopher Wren — astronomer, mathematician, the greatest architect of his age and an alumnus of Wadham College, University of Oxford. One definitely gets the sense, when talking with other illustrious alumni of this institution, that it has been built and sustained to last for eternity. Wadham College was founded by Nicholas and Dorothy Wadham in the reign of King James I. Nicholas Wadham (a Somerset landowner) died in 1609, leaving his fortune to endow an Oxford college in the very capable hands of his 75-year-old widow Dorothy. This remarkable lady overcame numerous challenges to open the college within four years of her husband’s death and continued to support and sustain it until her own death in 1618. The college only accepted men initially, but it went on to become one of the first colleges at Oxford to allow women as full members in 1974.

On September 1, 2012, Lord Ken Macdonald, one of the UK’s top criminal lawyers and a former Director of Public Prosecutions, will commence as Warden (head of the college). Lord Macdonald was Director of Public Prosecutions for the UK from 2003-2008. In 2007 he was knighted for services to the law. In July 2010, he became a Liberal Democrat Peer and a member of the House of Lords, with the title Lord Macdonald of River Glaven QC. He is a visiting Professor of Law at the London School of Economics and member of the Advisory Board of the Center for Criminology at the University of Oxford. I had the opportunity to chat with him about his international thinking for Wadham College, among other things.

What do you see as the most important contributions an Oxford education makes to the intellectual and character development of the individual?

Oxford is about education at a very high level. Broadly speaking, entry is very competitive. We’re looking to attract the brightest kids from the broadest possible backgrounds. Once we understand our incoming students’ potential, we deliver a pretty intensive program of work designed around developing that potential fully. We want them to be the best that they can be. Right from the start of their careers as freshmen, our undergraduates are taught by college fellows who are world leaders in their field of interest, either one-to-one or in tutorial groups of two or three. So they are getting the benefit of very high level, personalised intellectual input from the start. This approach to teaching is one of Oxford’s great strengths. Essentially, we want to provide an environment in which people can progress as far as they are capable of going.

What are your views about standardized tests and the university admissions process? How do you ensure you are getting the brightest kids out there for Wadham?

Let me give you my view of this from what I have seen at Wadham. All the young people who enter Wadham from the UK will have done very well in their A Level examinations. They will have achieved Grade A or A* in their subject areas.

Additionally, we have reverted to what used to happen thirty or forty years ago. Oxford now sets its own entry exams, that is, tests for individual subjects. For example, if a student wants to read English, the student has to take a specific test. There are also special tests for Law, Politics and Philosophy, languages and so on. The examinations are very good at assessing people’s potential as much as their past experience. The tests include things that the students may have studied at A Level but there may also be questions that are well off the school syllabus. Students will be expected to show some creativity when answering them. That’s an important part of our assessment process. The next part of our assessment process is that every candidate under consideration is interviewed. They are interviewed by the world-renowned tutors who will be teaching them should they be accepted. I sat in on some interviews with students who wanted to study German as well as interviews for students who wanted to study Classics. In each interview, the candidate was given a poem in English twenty minutes before he came in to see the tutor. The tutor then asked him to deconstruct the poem and to critique it. The process gives the tutor an opportunity to assess the student’s ability to think creatively and of course, under pressure. It is a challenging process but it is designed to evaluate what a person may be capable of in the future as well as where that person is at the moment.

I assume you want to attract students from anywhere in the world? Those students are going to have studied different curricula in different education systems. How will you assess those students?

Wadham is very relaxed about students coming from a different kind of education background. That’s not a problem for us. Let’s suppose you had a student coming from the United States. Their school curriculum is going to be different from ours in the UK. In the United States, students do not specialize in subject areas while in secondary school as they do in the UK, and so American students may not yet be at the level of those students coming from an English school. That doesn’t necessarily trouble our fellows because they are looking for future potential as well as the good examination results that you will have received to date.

We have world-class universities in the UK and I think we see the rest of the world as a big opportunity in continuing to develop them. UK universities have as high proportion of international students as any other country in the world, and that is particularly true at Oxford. For instance, Wadham accepts a group of students from Sarah Lawrence College in the US every year. This has been a very successful program. I teach graduate classes at the London School of Economics and I would say 70% of my students are from outside the UK. Wadham is one of the strongest colleges academically at Oxford and I am particularly keen that we increase the number of incoming students from North America because there is obviously so much talent in those countries. Many of our foreign graduate students come from North America. We also have many undergraduates from around the world, especially from China, Hong Kong, India and Europe. Obviously, the larger the pool of bright students you have to select from, the higher the intellectual quality of your student body.

What’s your view on international assessments such as the IB?

I am quite keen on the International Baccalaureate and some schools in the UK have now introduced it. I personally think A Levels are a little too specialized. For example, my son is currently doing A Level English, History and French. If he was doing the Baccalaureate, he’d be doing more subjects and I personally think that is better. UK academic institutions are very aware of the international marketplace. A bright student applying from a North American school to Wadham will be assessed firstly in terms of the context of the education they have had to date and secondly in terms of the potential they show through the special Wadham assessment test and the interview. We would not necessarily turn down a student because they were not at A Level standard in a particular subject. If we thought they were capable of getting up to speed and of thriving at Oxford, that would be sufficient and we would welcome them with open arms.

Technology presents opportunities and challenges. How do you view the role of technology and the Internet in higher education?

First of all, I believe the Internet is a fantastic resource for students. Students now have information at their fingertips that I only dreamt of when I was a doing my A Levels. I had two or three textbooks and what you could get out of the library. So students now have fantastic resources. Secondly however, this easy availability may present a risk, which is the temptation to get everything you need at the last minute — you may become over-reliant and get out of the habit of thinking for yourself. The third thing is the problem of plagiarism and that’s an issue all universities face. We have to be vigilant. The internet, when properly used, is a fantastic resource for students. Additionally, the ways in which students can communicate with each other, with their teachers, throughout the college and the world are brilliant. Putting aside the challenges, I believe that technology is going to be at the heart of how education is delivered during the course of this century.

Picking up the reins in your new role as Warden of Wadham, any final thoughts you would like to add?

I think educational institutions are wonderful things. They are capable of building communities, spreading knowledge, developing civilization — all of these important things. It is impossible to overestimate how important educational institutions are to society. We need to invest in them. I don’t just mean in financial terms but in intellectual and emotional terms as well. What I want Wadham to be is a beacon for high academic achievement, for fairness in selection and for creating an international community in which students, fellows, and graduates can come together in intellectual drive. I think the universities in Britain are absolutely integral to the way we British see ourselves. They are important institutions and we need to nurture them.

More information on Oxford tuition costs for international students.

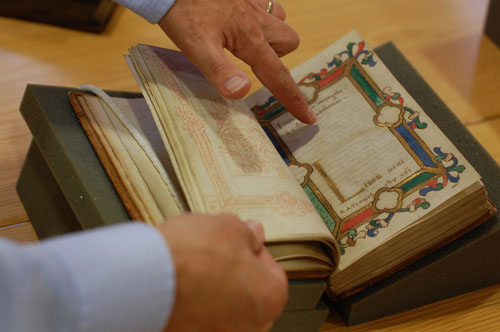

Photos courtesy of Wadham College, University of Oxford.

Thanks to HESA and the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.

In The Global Search for Education, join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (US), Dr. Leon Botstein (US), Professor Clay Christensen (US), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (US), Dr. Madhav Chavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (US), Professor Andy Hargreaves (UK), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (US), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finland), State Secretary Tapio Kosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Professor Ben Levin (Canada), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (US), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (US), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (US), Yves Theze (Lycee Francais US), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (US), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today. The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland.

Recent Comments