Is there a future for a US – India partnership in education?

In his remarks at the recent Brookings Institute conference in Washington, Deputy Secretary of State William J. Burns commented, “We are counting on India’s rise, not just as an economic partner, but as a global power — one that engages everywhere from Latin America to the Middle East to South Asia.”

Is there also a partnership opportunity in education? What might these two education systems be able to learn from each other?

In der US-, we have a significant poverty problem that has a large impact on the educational readiness of children from poor and low income families. 1 in 5 children live in poverty and 1 in 4 rural children live in poverty. 38.5% of rural children are eligible for free or reduced price school meals. The average cognitive scores of preschool-aged children in the highest socioeconomic group are 60% above those of low-income children. (Information provided by Save the Children US Programs)

DR. Madhav Chavan, CEO and Co-founder of the Pratham Organization notes:

“On the face of it, the two systems are at least a century apart and may have nothing to learn from each other. Indian educators would need to look at how the US schools evolved over the last two centuries, and the US counterparts may want to look at how similar the root causes of poor learning are in schools where children of the poor go. I have been thinking lately that the basic model of the school is fast becoming outdated in the modern times. The challenges India faces are also an opportunity to move away from the two centuries old model of schooling. US school systems have huge resources to try something new. Perhaps both sets of educators should sit down and ask what kind of schools are needed for this century and if they can be systematically developed over the next twenty years.”

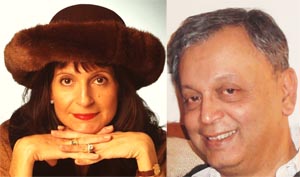

Diese Woche in Die globale Suche nach Bildung, DR. Chavan discusses the major issues facing India’s education system and some of the solutions Pratham (one of the largest non-government organizations working with under privileged children) is putting in place to deal with them. Pratham began by offering pre-school education to children in the slums of Mumbai. These programs were subsequently expanded to nearly every state in India. Pratham’s programs are aimed at supplementing governmental efforts. In 2005, it established the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) to quantify the problems of education in India. Im Januar 2007, it launched the Read India campaign to help India’s 6 zu 14 year olds learn to read, schreiben, and do basic arithmetic.

What proportion of adult Indians is educated?

Entsprechend der 2011 census figures, Ich glaube, dass 25% of adult Indians are illiterate. 50% are semi-educated. Of the remaining 25%, roughly 2 zu 4% have received a top class ‘elite’ Bildung, 10% have received a good education and are from the upper middle class, and the other 12% have received some college education and are from the middle class.

What are the issues India faces in their education system at each of the different levels of learning?

I think India faces two basic educational system problems at three different levels. The first issue is one of quantity. The second is one of quality. The three levels are the basic level, d.h.. the primary education (up to age 14), the secondary education (Ewigkeit 14 zu 18), and then higher education such as college and university. In all three levels, both issues of quantity and quality are the concern.

In our annual status of education survey we have learned the following. At the primary level, we find by 5th grade, in large numbers of Indian states, weniger als 50% of children can read a Grade 2 level text. Only about 40% can solve Grade 5 math problems. Und so, 50% of our children at the primary level are at a risk of not entering or not completing secondary education level. That’s what we face at the primary level. I believe that a large number of primary school students come from illiterate or semi-literate families who should be able to get additional support, including tutoring, to enable them to handle secondary education.

At the next level, that is secondary education and vocational schooling, the Indian infrastructure and the availability of trained teachers is very poor. My feeling is that we need to think beyond our existing educational learning curriculum, which is very linear. We need to become more innovative so that we can expand and improve learning at the higher levels.

Quality of testing and assessment (certification) is also a big issue. It is hard to say what our examination system actually examines with credibility. Beispielsweise, if you are a first class student in one corner of India as opposed to another corner in India, it can mean two different things. I believe a solution to this is a standardized test for all.

What things can organizations such as yours do to help students who are not achieving in the existing system?

In Indien, our first objective in many cases is teaching the child basic skills such as reading and writing. Our annual education survey also checks children’s competence in these basic skills and also their school attendance. We also interview parents. Right now our system just expects teachers to “complete the curriculum” regardless of whether children learn. So looking at the indicators and outcomes is the first step. Based on those results that I have explained above, our team can intervene to help with learning gaps that exist in certain school communities. When we have the schoolteacher and the volunteer (who come from the same community or village as the child) working in sync with the teacher, progress has been made.

I think there is a need to have a very strong bridge between home and school so that parents can be told how the child is doing, especially if the child is not doing well, and so that parents can also help the child in some way.

Our middle class families can make up the learning gaps in our schools with private tutoring. So many middle class Indian students are learning all day in school, coming home, having a quick snack, and then rushing off for several more hours of tutoring. This of course can make children overburdened and overstressed.

Have Indian children started participating in the PISA test?

Ja, India is participating in two states. So let’s wait and see how we do.

What do you think are the most important next steps to making the progress in the Indian educational system you would like to see?

We have to set short, mid, and long term outcome goals. We need to do this at the policy level, and so that means moving away from the current input oriented system we have. If we do that, we are addressing half the problem.

Zweite, we have to address our teacher training process. Teacher training in India is a big problem. Training needs to be revolutionized. In some states, they have tried to address it, but it comes up again and again. Some teachers have the knowledge, but that does not mean they can get the results from their students. Teachers learning how to teach and improving their practices is extremely important.

If these two things are done, then the third thing that we can address is how and what we test. We also need to open up our procedures for testing students. Credible standardized tests will be important to raise and maintain quality standards.

There is also too much emphasis on textbooks. I think we need to focus beyond books. Die Gesundheit, Sport, the arts and handicrafts can give children a wider experience of the world. Somehow childhood is missing in our education. I’d like to see children have the opportunity to explore more. It is interesting that India has so many artists and yet art is not a part of our school system. These are important things that we don’t define as knowledge. Being able to read and write is a critical objective. But our definition of education and knowledge has to expand beyond what we are currently teaching in schools.

Tumi USA (established in 1999) now has chapters in 15 major cities across the United States, including Boston, Chicago, Dallas/Fort Worth, Houston, Los Angeles, New York, North Carolina, and the San Francisco Bay Area.

Weitere Informationen: www.PrathamUSA.org

In Die globale Suche nach Bildung, beitreten C. M. Rubin und weltweit renommierten Vordenkern wie Sir Michael Barber (Vereinigtes Königreich), DR. Leon Botstein (US), DR. Linda Hammond-Liebling (US), DR. Madhav Chavan (Indien), Professor Michael Fullan (Kanada), Professor Howard Gardner (US), Professor Yvonne Hellman (Niederlande), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norwegen), Professor Rose Hipkins (Neuseeland), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Kanada), Frau. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgien), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgien), Professor Hugh Lauder (Vereinigtes Königreich), Professor Ben Levin (Kanada), Professor Barry McGaw (Australien), Professor R. Natarajan (Indien), Sridhar Rajagopalan (Indien), Sir Ken Robinson (Vereinigtes Königreich), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finnland), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), DR. David Shaffer (US), DR. Kirsten Sivesind (Norwegen), Kanzler Stephen Spahn (US), Yves Theze (Lycee Francais US), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Kanada), Professor Tony Wagner (US), Professor Dylan Wiliam (Vereinigtes Königreich), Professor Theo Wubbels (Niederlande), Professor Michael Young (Vereinigtes Königreich), und Professor Zhang Minxuan (China) wie sie das große Bild Bildung Fragen, die alle Nationen heute konfrontiert erkunden. Die Global Search for Education Community-Seite

C. M. Rubin ist der Autor von zwei weit Lese Online-Serie für den sie eine 2011 Upton Sinclair Auszeichnung, “Die globale Suche nach Bildung” und “Wie werden wir gelesen?” Sie ist auch der Autor von drei Bestseller-Bücher, Inklusive The Real Alice im Wunderland.

Folgen Sie C. M. Rubin auf Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Jüngste Kommentare