The desire for successful children in a performance-based culture often consumes us before we realize it. “More is better” might innocently trickle into the mindset, but before you know it, the winner takes all dynamics of a competitive society can easily become a part of our everyday lives. Whether it’s coming from inside or outside of school, the need for our children to succeed is coming at us fast and consistently.

I recently found myself pondering what style of parenting ultimately creates the best foundation for our children. Amy Chua (Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother) on the one hand proposed that the best way for a parent to prepare kids for a successful future is to stress academic performance, never accept a mediocre grade, and instill a deep respect for authority. Vicki Abeles (Race to Nowhere) was concerned that performance pressure on kids is destroying self-esteem and happiness, and stifling creativity.

Should self-esteem and happiness come before accomplishment, or accomplishment before self-esteem? Perhaps success might be a delicate balance between the two that we each must define for ourselves and then evaluate on a regular basis?

This is the first of three in depth looks at student health and engagement with learning. This week I have the pleasure of sharing the perspectives of Dr. Denise Papa, Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de Stanford. Pope specializes in student engagement, curriculum studies, qualitative research methods, and service learning. She founded and served as director of Stressed-Out Students (SOS), the predecessor to Challenge Success. O livro dela, Doing School: How We Are Creating a Generation of Stressed Out, Materialistic, and Miseducated Students, was awarded Notable Book in Education by the American School Board Journal.

Are you seeing an increase in the number of cases related to adolescent anxiety, stress or depression?

The answer is yes. We are seeing more cases in terms of higher stress levels and in terms of anxiety, depressão, and other diagnosed disorders than we have seen in the past. A study done by Stanford Medical Center a few years ago confirmed this (Dr. Jun Ma, 2005, Journal of Adolescent Health). You might say we are getting better at detecting mental health issues in kids, so you might wonder if that is the cause of the increase that we see. The experts believe that there is definitely something going on around this notion of kids being much more stressed these days – above and beyond the better detection rates.

Can we connect it to academic pressure?

Our Challenge Success survey (26 escolas, 10,275 alunos, 87% high schools, com 65% of them public) gave the kids a worry and stress scale. 67% of our sample said they are often or always stressed about school. On the qualitative question, isto é. “what if anything causes you stress,” the top ten answers from the majority of our students were school related. Ten or twenty years ago the top answer for a teen might have been family issues, divorce, bullying or sexual identity, but they would not primarily have been school related. Granted we were talking to high achieving schools and we were doing the survey in school, but even given that, the top answers were homework, testes, grades and competition to get into colleges.

Are we able to tell who the vulnerable child is?

The CDC uses GPA as one measure to predict student well-being. What we know at Stanford and other high achieving institutions is that you can have straight A’s and still be in distress. The typical or traditional ways of assessing mental or physical health issues for us are not as accurate anymore. Many of the suicide attempts or suicides that we are seeing at high achieving schools involve kids with good grades. To the outside world, these kids look like everything is okay. Em muitos casos, there may be signs that people missed. We have to get better at identifying these signs. The fact that the kid throws himself across the track the first day of AP week might suggest there is a link between academic stress and mental distress. But there are always multiple factors at play when a young person suicides. It can be very hard to tease out what part genetics, depressão, meio Ambiente, and impulsivity play. Depressão, which tends to run in families, is strongly linked to suicide, yet there are many people who never manifest depression and who never suicide in spite of having a strong family history of depression. What we do know is that high levels of stress increase the likelihood of depression manifesting itself. In this respect, we have an obligation to keep the level of stress in our children’s lives manageable. High levels of stress can cause distress and make our children vulnerable to a host of physical, cognitive and emotional problems.

Who or where is the stress coming from?

Most kids agree it is coming from all areas including parents, self-imposed pressure, and the schools. If you go further, the kids add college, college admissions, and the media frenzy over status, money and success. We call it a systemic cultural issue around a flawed and miscommunicated definition of success. One of the questions we ask the students in our survey is “How do you define success?” From my experience of asking parents the same question, the response I get is “felicidade, saúde, giving back to society” – all the things you would expect a parent to say. The first response we get from the kids is “dinheiro, grades, test scores.” And so we are talking about external definitions versus internal. How are these messages getting so distorted when parents and kids are living in the same house?

Kids in the same family can be very different in terms of their personalities and consequently their outlook, despite being exposed to the same influences. Pensamentos?

There are some kids that parents need to hold back. Por exemplo, the perfectionist child. You have to say, “This is too much.” You have to play the parent card and say, “It is bedtime or you are not taking that extra class.” And then there are other kids that might need a little kick in the pants – a little more attention and urging them to think about schoolwork and completing homework, because it’s a good thing now and then for a kid who isn’t spending much time on school. But you have to be careful. We know that parents can cause a lot of duress. We also do workshops for parents on values where we look at the question: Are your actions aligning with your values? Por exemplo, are you saying one thing while at the same time pushing your kids to take extra classes they don’t want, or hiring lots of tutors.

What can be done to better address children and adolescents compromising emotional and physical health as they deal with performance pressure?

This is what we focus on at “Challenge Success.” I believe there should be a process to dealing with performance pressure. I believe there should be intervention. We also don’t believe there is a one size fits all solution. It depends on the level you are working with and the institution you are working with. There also has to be a multi-stake holder team approach. So we work with schools, parents and students to develop a plan of action specific to their school around the issues of student health, bem-estar, and engagement with learning. We give school teams a coach who works with them on a consulting basis for a year. We say that every kid needs PDF (playtime, downtime, family time) every day, no matter what the age. We talk about the research we’ve done and how you can protect PDF at any age. Para os pais, we do six week education courses (live and online). We ask them to think about their value system and come up with their own definition of success and an action plan of how they’re going to apply this vision to their parenting practices. We have seen schools do a lot of different things that has definitely dialed down the stress level and improved the health and well-being of the kids. We use hands-on solutions to what is a very large cultural problem, and schools keep coming back. We are definitely making a dent. If you don’t have healthy kids, they are not going to be successful, period!

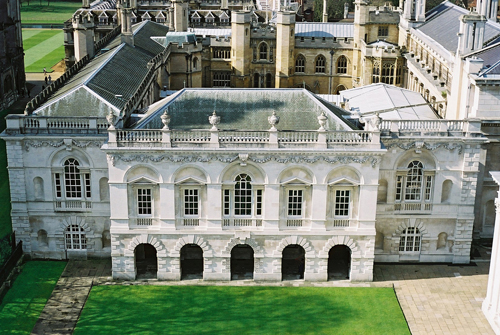

Photos courtesy of Stanford University School of Education.

Em A Pesquisa Global para a Educação, se juntar a mim e líderes de renome mundial, incluindo Sir Michael Barber (Reino Unido), Dr. Leon Botstein (US), Dr. Linda, Darling-Hammond (US), Dr. Madhav Chavan (Índia), Professor Michael Fullan (Canadá), Professor Howard Gardner (US), Professor Yvonne Hellman (Holanda), Professor Kristin Helstad (Noruega), Professor Rose Hipkins (Nova Zelândia), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canadá), Senhora. Chantal Kaufmann (Bélgica), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Bélgica), Professor Hugh Lauder (Reino Unido), Professor Ben Levin (Canadá), Professor Barry McGaw (Austrália), Professor R. Natarajan (Índia), Dr. Denise Papa (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (Índia), Dr. Diane Ravitch (US), Sir Ken Robinson (Reino Unido), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finlândia), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OCDE), Dr. Anthony Seldon, Dr. David Shaffer (US), Dr. Kirsten Immersive Are (Noruega), Chanceler Stephen Spahn (US), Yves Theze (Francês Lycee EUA), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canadá), Professor Tony Wagner (US), Professor Dylan Wiliam (Reino Unido), Professor Theo Wubbels (Holanda), Professor Michael Young (Reino Unido), e Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) como eles exploram as grandes questões da educação imagem que todas as nações enfrentam hoje. A Pesquisa Global para Educação Comunitária Página

C. M. Rubin é o autor de duas séries on-line lido pelo qual ela recebeu uma 2011 Upton Sinclair prêmio, "The Search Global pela Educação" e "Como vamos ler?"Ela também é o autor de três livros mais vendidos, Incluindo The Real Alice no País das Maravilhas.

Comentários Recentes