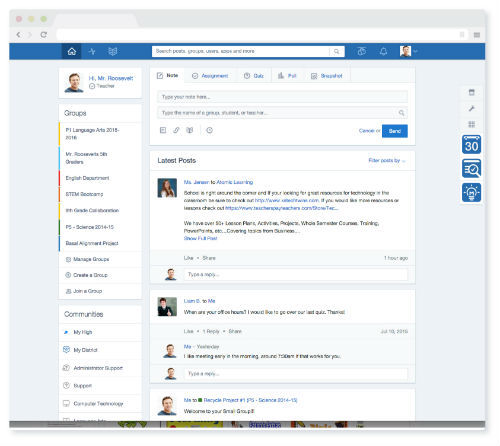

Based in San Mateo, California, Edmodo is the number one K-12 social learning network in the world. The goal of the Edmodo platform is to engage learners with knowledgable peers and impactful content, and it is estimated that 50 million educators in 190 countries are currently doing just that. “Edmodo has been fortunate in having some of the best teachers already on the platform. These teachers have shared millions of pieces of content,” explains Edmodo’s CEO Vibhu Mittal. “Resources shared range from a short pointer with immediate applicability to long, thoughtful analyses of interesting questions and possible solutions that might take a teacher days or weeks to think through and write,” he adds.

Blended learning is growing rapidly and it involves much more than introducing technology into global classrooms. What are the benefits and challenges researchers are discovering? What are the issues and scenarios to consider in the future? Vibhu Mittal and Michael Horn, co-founder and executive director of education at the Clayton Christensen Institute, join me today in The Global Search for Education to talk about learning in a world driven by innovative online educational tools.

You have done research with teachers moving into blended learning environments. What are some of the challenges you have seen teachers face and how have these discoveries shaped your thinking regarding the likely evolution of education systems?

Michael Horn: The biggest challenges teachers seem to face is that the bulk of their preparation and training has been all geared toward teaching in a traditional classroom, and many of those teaching practices just aren’t that relevant in a blended-learning environment. In particular, ways of managing a class, preparing for class, using data, and structuring the time in a blended-learning environment are just fundamentally different from those activities in a traditional classroom. Teachers typically say that teaching in a blended-learning environment is harder than the traditional one – but that there isn’t a chance they would go back to the traditional classroom. I think the reason is that in a blended-learning environment, you’re truly able to see where each individual student is in a way you aren’t in a traditional environment, and you’re able to reach and serve each student in a personalized way you aren’t as well – but this can be more work. Teachers don’t want to sacrifice the opportunity to serve their students better though.

My sense is that this means in traditional classrooms, we’re going to see less of the big shifts to fully flex models of blended learning where students have full control over their path and pace of learning, and instead see more initial shifts through the adoption of things like Station Rotation models and Flipped Classrooms.

It is so important to balance privacy of student data with the ways technology enables the monitoring and control of data. What are the most important lessons you have learned about this so far?

Vibhu Mittal: Who owns student data? Is it the student or parent? The school or the district? These are difficult questions, often with no single good answer. To date, the privacy conversation has been very industry-focused, with more attention being called to how third parties, like districts and edtech providers, handle data, rather than users themselves. Most of the discussion has been focused on how data should not be used, rather than on how it should be used. There are some cost/benefit analyses that we should all be thinking about when we collect data, agree to let others organize it, index it and use it. In a day and age when even defense computers can be hacked into, it behooves us all to store the absolute minimal data that we can most effectively use to impact learning outcomes and no more.

Michael Horn: Privacy is of course critical, but at the moment the dialogue nationally is focusing far too much on the privacy aspects surrounding data rather than the important usage data has for driving personalized learning and supporting students, teachers, and parents. If we’re not careful, we risk cutting teachers off from critical data that can help them better serve students. Blended learning is showing how we can use data to understand what each student knows and doesn’t to help teachers drive better learning; software programs are getting better at using student data to suggest online and offline experiences to help students as well. Many of these providers though are small at the moment, and placing too many reporting restrictions on them through regulation could stifle innovation. The flip side is this: edtech companies must do a much better job of not only complying with current regulations, but also proactively leading the way by adding more security features and better privacy policies in order to win the trust of students, parents, and teachers. There’s not enough of that going around right now either.

What do you perceive to be some of the intended and unintended benefits of the Edmodo platform? How have these discoveries shaped your thinking regarding technological advances?

Vibhu Mittal: Every technological advance has intended and unintended effects. It’s often the unanticipated effects that are more interesting because they grow organically out of an ecosystem that a platform allows. In Edmodo’s case, we intended for teachers to have a streamlined workflow and simple classroom management tools that would afford them more time to focus on teaching. The collaboration among teachers and students was also an intended benefit, however, I don’t think we had quite anticipated the rapid rate at which teacher-teacher collaboration took off, or how many educators would come to use Edmodo as a professional development platform in tandem with teaching efforts. It has been inspiring to watch the network evolve into a forum that supports both teachers and students in their learning careers.

When books came along, oral histories became less important. Give us some examples of similar scenarios we are witnessing in education reform currently because of technological advances.

Michael Horn: Something similar is actually taking place; just as books allowed knowledge to become more diffuse, online learning resources are doing the same. What that means in this case is that the teacher isn’t the primary fountain of knowledge anymore, and activities where they are transmitting knowledge orally and live to a large group of students are fading in importance. As a result, we’re seeing increasing shifts away from the blackboard, whiteboard, and electronic whiteboard as large group knowledge transmission devices.

Vibhu Mittal: The ubiquitous adoption of mobile devices will be one of the great change catalysts for humankind. For a long time, access to information was jealously guarded. Books were scarce and expensive. As phones and information access proliferate, access to information is no longer the divide that separates the haves from the have-nots. The ability to remember facts becomes less important once ubiquitous search becomes common. Just as calculators made it possible to not be good at mental arithmetic and still be able to calculate, wireless connectivity in the palm of your hand to all the information in the world will change the dimensions that matter. The ability to find and access teachers and peers, share and analyze information, filter through noise and a firehose of signals will become more and more essential. Will cognitive efforts and training change as well? While we cannot predict how, I think the answer is clearly an emphatic yes!

Please give us your thoughts on scenarios we face in the years to come regarding technological changes in education.

Michael Horn: Technology is doing two critical things right now in education. It’s creating more opportunities for personalized learning for students, and it is freeing up teachers from delivering whole-class instruction to a cohort of students all in different places of their own understanding to spending far more time on the critical learning functions that too often get short shrift in schools today – or are done without students having the core knowledge base to take advantage of them. For example, teachers can spend far more time working with students one-on-one and in small groups, designing learning experiences for students, helping students work on meaningful projects, leading Socratic discussions, and mentoring students to develop the skills of critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity and discover their passions. Correspondingly, that means we need to support teachers in this change in practice, and we need to create more personalized learning experiences for teachers as well so that we can acknowledge and certify their mastery of certain parts of their craft and support them in the areas where they need to and want to improve.

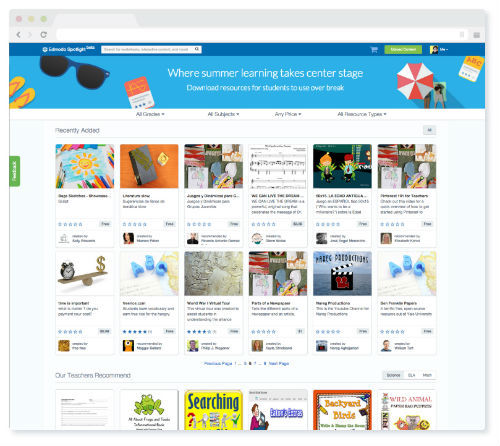

Vibhu Mittal: Every educational advancement thus far has been a faithful mapping of the real world to the virtual world (i.e. MOOCs, online quizzes vs. paper quizzes). But what about integrating modalities that have no real world analog into K-12 education? Adaptive learning is one such modality that could have amazingly beneficial ramifications. Edmodo provides the learning ecosystem in which blended and adaptive learning can flourish. The combination of tools accessible on our platform, the power of our network and our new content repository help educators map new learning pathways that will shape how next-generation learning is defined and understood on a global scale. The single biggest mitigator of poverty in the world will likely be education and information access, not monetary resources.

(All photos are courtesy of Edmodo)

Join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. MadhavChavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. EijaKauppinen (Finland), State Secretary TapioKosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Geoff Masters (Australia), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (LyceeFrancais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today.

The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland, is the publisher of CMRubinWorld, and is a Disruptor Foundation Fellow.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments