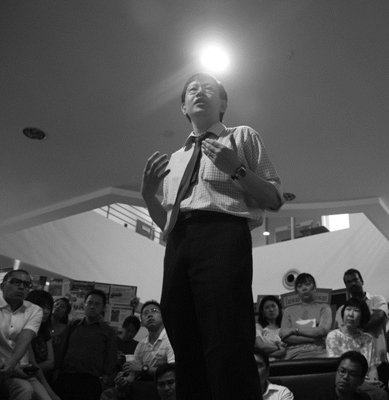

Singapore’s education institutions are considered among the most advanced in the world with regard to information technology. This week in The Global Search for Education, I invited Dr. Pak Tee Ng in Singapore to update us on how Singapore’s Ministry of Education (MOE) continues to support its public school system with Information and Communication Technologies (ICT).

Dr. Pak Tee Ng is Associate Dean, Leadership Learning, Office of Graduate Studies and Professional Learning, and Head and Associate Professor, Policy and Leadership Studies Academic Group, at the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Republic of Singapore.

Can you give us the background to Singapore’s Information Technology plan for its school system and also tell us what one would expect to find in primary and secondary public school classrooms currently?

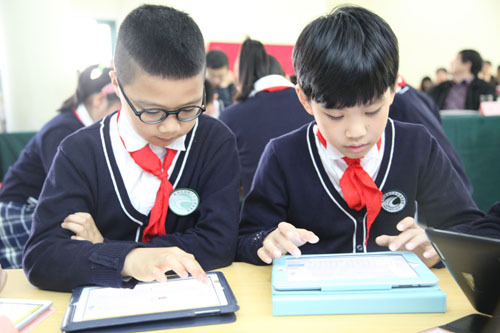

Singapore has been faithfully implementing a master plan since 1997 for integrating technology into education. Masterplan One (1997-2002) started out by aiming to allow students to have computer usage for 30 percent of their curriculum time in fully networked schools and at a computer to pupil ratio of 1:2. Masterplan Two moved beyond the provision of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) resources to encourage teachers to use ICT profitably in teaching and learning. The current Masterplan Three (2009-2014) builds on the platform laid by the first two Masterplans to transform the learning environments of the students through ICT and equip the students with the critical competencies to succeed in a knowledge economy.

Currently, one could expect wireless internet connectivity in the school compound and at least a computer with projection equipment in the classroom. But most teachers and students have their own laptops or other mobile ICT devices. In the future, all Singapore schools will be connected to the Next Generation Broadband Network (NGBN), which will provide ultra-high speed wireless connectivity. This is an example of how the MOE has supported schools in using ICT in education. The MOE also provides a training program to develop a group of competent practitioners in their ICT-related pedagogies and coaching competencies. With an average of about 4 such ICT mentors in each school, these ICT mentors champion and mentor teachers on the effective use of ICT in their respective disciplines.

How have you handled the challenges of educating teachers to use blended technology systems in the classroom? What additional ongoing professional development is given to teachers to ensure they integrate technology effectively in their classrooms?

The MOE provides our teachers with many professional development opportunities regarding the use of ICT in classrooms. Schools also have many Professional Learning Communities (PLCs), and some of these PLCs explore how teachers can use blended technology in teaching and learning.

However, changing pedagogy is a very personal matter. Therefore, other than professional development, we use the strategy of exposing our teachers to the technological possibilities and supporting them in exploring new pedagogies with technology. The focus is not on technology. It is on using technology to enhance teaching and learning. Two examples of this strategy are the eduLab programme initiated by the MOE, and the Classroom of the Future (COTF) at the National Institute of Education (NIE). The eduLab showcases experiments trialed in schools. Educators who visit eduLab can learn more about how certain local schools have infused innovative ICT practices into lessons and classroom activities. The COTF showcases what classrooms and learning environments (including homes and public places) can look like in the future to trigger the imagination of the teacher. Through such exposure, we hope to spread mature ICT innovations and successful practices and generate interest among teachers.

What are some of the best hands-on examples of teachers successfully integrating technology in their teaching practice?

It is difficult to say which hands-on usage of ICT is considered as a best example. This is because teaching and learning is a contextual activity, and ICT is not an end but a means to enhance teaching and learning outcomes. However, there are a few examples. One is the use of GroupScribbles (GS) technology to support generalized coordination among students and the teacher through the convenient feature of sticky paper notes in a virtual medium. Another is the use of the online virtual world of Second Life, where students can role-play and deal with legal and moral issues in the ‘safety’ of the virtual world. The use of e-discussion forums to generate discussions among students is also gaining popularity.

Many believe technology is helping to level the playing field for different types of learners. Do you think so in the light of Singapore’s experiences?

Yes and no. From a certain perspective, it does somewhat level the playing field. Students who need more time to learn have the opportunity to review lessons and study at their own pace with the availability of online lecture notes and discussion boards. This allows them to catch up with those who learn more quickly. However, technology, like any other learning approaches, favors students who enjoy using it. Learning comes easier to those who are good with technology and, conversely, becomes more challenging for those who are not.

We also have to ask what we mean by “leveling the playing field.” Technology comes at a cost. Computers, other ICT gadgets, and Internet access can be costly. Therefore, those who can afford ICT equipment and services will definitely have better access to technologically-driven education, compared to those who are not as financially well-off. Therefore, ICT creates an equalizing effect on some aspects of learning and widens the gap on others. Regarding this issue, what has been done in Singapore is that the government funds schools so that students will have access to computers in school. There are also subsidy schemes to help students buy their own computers. Further, the focus is on using technology as a tool for teaching and learning, rather than on technology in itself. In this way, the potentially uneven playing field is made more even.

With the technology revolution showing no signs of slowing down, the teacher’s role and the nature of the classroom is changing. What might learning look like 5 years from now in terms of the balance between the nature of the teacher’s role and online learning?

In 5 years time, there will possibly be an increase in the proportion of online learning compared to face-to-face classroom contact. However, precisely because of that, the teacher’s role will become more important than ever. Firstly, teachers must be able to facilitate e-discussion and help students make sense of the large volume of data and discourses in these e-forums. This requires a high level of facilitative and synthesizing skills. Secondly, face-to-face contact, which is reduced, becomes more valued and will be reserved for higher order thinking and learning, rather than mere information transmission.

Moreover, in years to come, educators will realize that it is essential to tap on students as a source of ICT intelligence. At this moment, teachers tailor pedagogies for their students because students are treated as ‘minors’ to be taught. However, students are born in the digital age, unlike many of their teachers. Therefore, in the future, the role of the teacher is to learn how ICT can be wrapped around students in their natural activities, not fit them into fixed technologies and processes, so that the students may be brought directly into the dynamics of ICT teaching and learning in school.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Pak Tee Ng.

In The Global Search for Education, join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. Madhav Chavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finland), State Secretary Tapio Kosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Professor Ben Levin (Canada), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (Lycee Francais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today. The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments