It is one of the world’s leading academic centers and oldest universities; a self-governed community of scholars with a reputation for outstanding academic achievement. Like all of the world’s greatest universities, Cambridge University is looking for the very best students, who are not just passionate about their studies but also have the potential and drive to succeed. So given the intense competition to be accepted, is this world-renowned academic institution seeing an increase in student anxiety and stress? I had the opportunity to chat with Dr. Mark Wormald, Senior Tutor at Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he has been Fellow and College Lecturer in English Literature since 1992. As Senior Tutor, he is responsible for education and welfare in the College, a community of some 440 undergraduates, 280 graduates, és 70 Fellows.

Are you seeing an increase in the number of cases related to adolescent anxiety and stress that you believe might be tied to academic pressure?

We are seeing an increase in stress related or medical issues amongst our students, requiring them to take time out, and those numbers have been going up year on year. I don’t think I could attribute all of it to academic pressure. There are a number of issues and every case is different. We’ll see typically between half a dozen to a dozen students who have to take time out and have to start their academic year again, but the causes can be everything from bereavement to physical or medical conditions. I would say about two or three of those cases might be academic stress-related out of a population of 440.

British students have been brought up on modular exams. Until they complete secondary school, they are examined annually, and they can retake their exams if they need to. At Cambridge, azonban, there is no possibility of retakes. So our students are used to academic pressure of a kind, but are pretty fixated on those end of year exams. Our challenge is to support our students, get them interested in their subjects, help them in the course of three terms to enjoy their study for its own sake, cope with the final exams, and learn how to deal with that pressure. And they do. They do very well and so I think the academic pressure is manageable.

The drop out rate is one way to measure. Some may suffer quietly. Are you able to tell who the vulnerable child is? What’s the process once a child with problems is identified?

It is not always immediately apparent from the application process that an applicant might have issues. Például, it’s not always in the references that are written for students. There may be family issues that don’t emerge. How we tell once a student is accepted whether there is a problem is when a student starts missing academic appointments or does not meet with their Director of Studies or their Tutor. At Cambridge, the Tutor is responsible for a student’s pastoral welfare. Once students miss those meetings or start missing supervisions, then that is a sign that we gently need to enquire how things are going. Vagy, if people are not picking things up from their pigeon holes at the porter’s lodge. That’s another example of how we try to nip things in the bud. The reasons could be some kind of illness, a personal problem or, they feel they’ve made a mistake and are not up to the Cambridge program. When a student gets behind that only exacerbates the problem and that then turns into despair when you discover you are three weeks behind in an eight-week term. Nipping problems in the bud is possible in most but not in every case. There can be problems that have nothing to do with academic work but that just manifest themselves at times of academic stress. At Cambridge, azonban, we do have a 99.5% retention rate; ez, 99.5% of students admitted pass their exams with honors.

A few years ago the British education system introduced more exams, so we have the GCSE’s, then AS, then A2. I think because of teacher anxiety in terms of preparing students for their exams (azaz. teacher accountability), a lot of the student stress may be internalized from their teachers. I think the system has almost become too narrowly goal oriented. We actually have to work pretty hard with incoming students to say: enjoy the program from week to week. At Cambridge we don’t have mid terms and term papers contributing directly to their final grade. Our preparation process is different. We are not involved in examining them at the end of the year. A board of examiners is responsible for that. We have to prepare them for those exams but it’s separate and we try to keep a gap between. The real work for us begins in the summer term because students will think that they have to work harder than other students around them e.g. they have to spend more time in the library because they see others doing that. Our work is to ensure we work with them to get them to relax, to get them to take time off and to ensure they work effectively but don’t overwork. I think we have gotten better at that over the last 15 vagy 20 év.

Are there any specific initiatives or programs that you can discuss that have been effective to help incoming students adapt to University?

I think we do recognize more formally now that there is a real gap between styles of learning and expectations on students between school and university. We are developing a whole series of online programs and workshops that we call at Cambridge Transkills. These are focused on bridging the transition for students between school and university. We want to be much clearer than we have been in the past as to our expectations of students. For example we expect students to be much more disciplined about time management and about their study skills. We want to make sure that teachers at Cambridge are much clearer about their expectations of what an essay might be as well as reminding students that an essay means a try, an attempt, rather than the definitive last word on a topic. Some of these students think that is what is expected coming from school. So taking that pressure off them and saying, “Think of it as an experiment and try different things.” That is beginning to work and I think that is countering a sense of dauntedness that you are suddenly going to be taught by world experts and expected to cope with a massively increased speed and intensity of work as well as massively raised expectations. It’s a way to say to students, “Take things a week at a time and you will be all right.” We believe this will help students perform better academically as well as avoid the feeling that they were plunged in the deep end and expected to sink or swim.

One other thought. Students these days, mint mi mindannyian, are much more used to expressing emotion, to sharing a sense of anxiety, than their predecessors were twenty years or so ago. There is perhaps occasionally something facile about this expressiveness. We all have cell phones, skype; vocalizing something, to a friend or family member, sometimes makes too palpable a niggle or a worry that would have passed by the time you reached the end of the queue for a pay phone. Sometimes we have to remind students that a little anxiety is normal, and that learning to deal with pressure by containing it or getting used to it is a necessary skill.

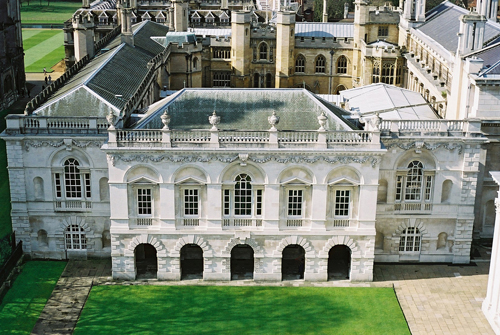

Photos courtesy of Cambridge University and Stephen Bond.

In A Global Search for Education, velem és világszerte elismert szellemi vezetők többek között Sir Michael Barber (UK), DR. Leon Botstein (US), DR. Linda Darling-Hammond (US), DR. Madhav Chavan (India), Professzor Michael Fullan (Kanada), Professzor Howard Gardner (US), Professzor Yvonne Hellman (Hollandiában), Professzor Kristin Helstad (Norvégia), Jean Hendrickson (US), Professzor Rose Hipkins (Új-Zéland), Professzor Cornelia Hoogland (Kanada), Mrs. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Professzor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Professor Ben Levin (Kanada), Professzor Barry McGaw (Ausztrália), Professzor R. Natarajan (India), DR. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), DR. Diane Ravitch (US), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professzor Pasi Sahlberg (Finnország), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), DR. Anthony Seldon, DR. David Shaffer (US), DR. Kirsten Magával ragadó Are (Norvégia), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (US), Yves Theze (Lycee Francais US), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Kanada), Professzor Tony Wagner (US), Professzor Dylan Wiliam (UK), DR. Mark Wormald (UK), Professzor Theo Wubbels (Hollandiában), Professzor Michael Young (UK), és professzor Minxuan Zhang (Kína) mivel azok feltárása a nagy kép oktatási kérdés, hogy minden nemzet ma szembesül. A Global Search Oktatási közösségi oldal

C. M. Rubin a szerzője a széles körben olvasott internetes sorozat, A Global Search for Education, és szintén a szerző három eladott könyvek, Beleértve The Real Alice Csodaországban.

Kövesse C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Legutóbbi hozzászólások