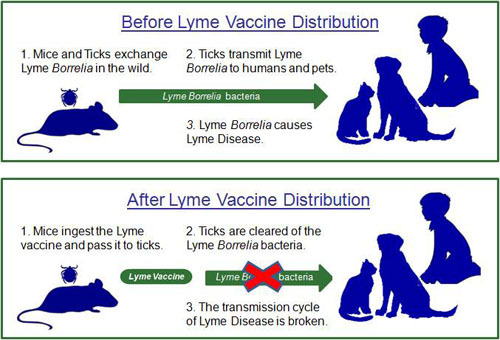

What if we could vaccinate the white-footed mice that account for the majority of the transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi (the cause of Lyme disease) and significantly reduce the level of tick infection?

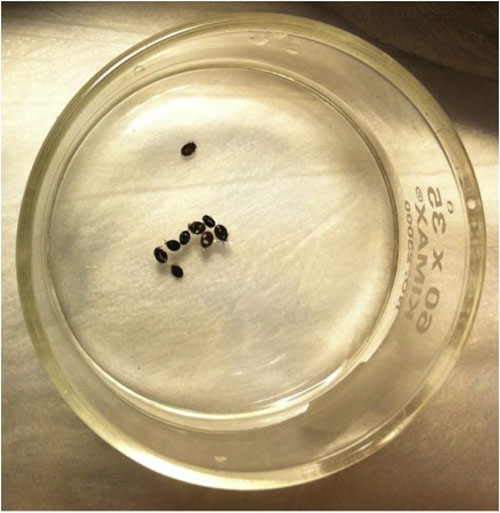

An oral bait vaccine was distributed to white-footed mice. The mice created antibodies in response to the vaccine. When ticks later fed on the mice, the ingested antibodies killed the Borrelia and prevented the transmission of Lyme disease. Along the same lines as this product, now being commercialized by US Biologic, the USDA National Wildlife Research Center has distributed an oral bait vaccine to wide areas of the eastern U.S. for over ten years to stop rabies, and it has been highly successful.

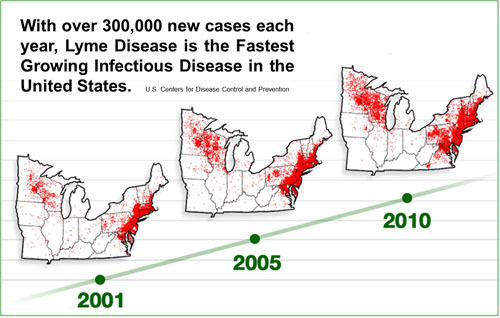

Lyme disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), affects over 300,000 people in the U.S. each year and can cause severe damage to joints and the neurologic system. The CDC recently linked Lyme disease with several deaths due to cardiac disease caused by Borrelia.

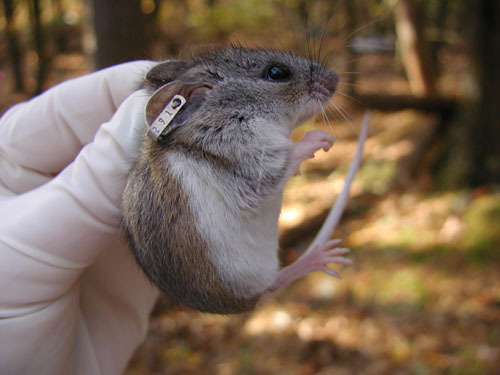

To discuss the next steps for this novel mice vaccine technology, I am joined today in Part 16 of Ticks by US Biologic board director, Dr. Tom Monath, and the Cary Institute’s Dr. Rick Ostfeld, who led the field research in New York to test the efficacy of the vaccine (invented and produced by Dr. Maria Gomes-Solecki).

Tom, how will the oral bait be distributed to the mice in their habitats?

Our primary method of distributing the pelletized Lyme vaccine will be to broadcast the pellets by hand, focusing on public lands like playgrounds, hiking trails, and campgrounds, among others. We can also broadcast from the air to treat larger areas. In the future, we will explore using simple feeding stations on private lands, like someone’s backyard. Feeding stations are small boxes that contain the pellets and allow access for mice.

How often will you need to distribute the bait?

Mice live for about a year in the wild. We will distribute the vaccine pellets several times throughout the summer, to vaccinate the multiple generations of mice born each year.

Which kinds of habitats were included in the study?

The study authors chose the locations of the control and test fields carefully. All study sites were within a Lyme disease endemic area– Dutchess County, New York. All sites were located on private land, to ensure the area wouldn’t be disturbed.

Which distribution approaches were the most effective?

The field study required that mice actually be trapped, enabling sampling of the ticks infesting these animals and the taking of blood samples to test for antibodies resulting from the vaccine pellets. For this reason, the vaccine pellets were placed in small live traps. “Broadcast distribution” is substantially more effective and resembles the efficient oral bait vaccine program used for rabies control in the U.S.

Why does the reduction in the infection rate increase over time?

The study data suggested a cumulative effect over several years on the rate of infection in nymphal ticks, the stage of the tick most important in transmission of Lyme. With immunization of mice each summer, fewer nymphal ticks and mice become infected and an increased proportion of mice surviving the winter are immune to Lyme disease. Thus, the force of infection in the following year is reduced. Mice only live for about a year in the wild. However, ticks live for two years. It took several years of immunizing mice and reducing overwintering infected ticks for the full effect of vaccination to appear.

After only one year, the study shows a drop of 23% of nymphs that carried Lyme. After five years, the presence of Lyme dropped by 75%. We can optimize the pellet distribution process to accelerate that process. If we continued to deploy the vaccine pellets and continued to monitor, we believe the infection rate would have dropped further.

Is there anything else that could be done to increase the speed of reduction in the tick infection rate?

We have the first solution, of which we are aware, that can reduce the amount of Lyme disease being transmitted. With that said, we fully support any method that has been proven, through a rigorous scientific method, to be an effective and safe intervention on a wide scale.

Pesticides used alone are not sufficient to prevent Lyme disease. There is considerable interest in integrated methods of Lyme disease control that would bring together the vaccine pellet with other approaches, including selected pesticides to reduce tick density. There is also an argument for controlling deer populations, which is where ticks breed.

What about the many different strains of the bacterium? Will the vaccine immunize the mice against all the different strains currently identified?

In North America, a single species Borrelia burgdorferi causes Lyme disease, and the OspA protein of this species does not show significant variability. We know that the vaccine pellet we use will be highly effective across the Northeast states, where more than 95% of Lyme disease occurs in the U.S. In Europe and Asia, five or more Borrelia species cause Lyme disease. We will develop vaccines to address these challenges.

Who do you see as the logical parties to handle distribution of the oral bait to the mice?

Because of their successful experience with the oral bait vaccine program to prevent the transmission of rabies, we are following the model created by the USDA National Wildlife Research Center, which has a long history of managing distribution and of monitoring resulting changes.

State and local health departments will be an important group in administering Lyme disease control programs, and they, like the USDA, have a long history of working to control these types of diseases. We also will involve private organizations. Pest management and lawn service companies are logical distribution partners.

On what scale in terms of quantity and frequency does the oral bait vaccine have to occur in order to be effective in a given area?

The study shows efficacy on an acre-by-acre basis, so there is an effect in even small areas. However, mice and ticks are everywhere, so to curtail transmission, a wide distribution is necessary. The pellets are very cost-effective, and treatment costs less than $20 an acre. On the average, this equates to less than $2 per protected citizen in states affected by Lyme disease. We will distribute the pellets several times throughout the summer months to ensure each generation of mice born over the summer has the opportunity to eat the pellets. It’s similar to usual schedules of immunization used in many vaccines. The first dose primes the immune system, and subsequent doses boost immunity.

What is the possibility of adding other pathogens such as Babesia and Anaplasmosis into the same bait?

You ask an exciting question. The current technology, we know, disrupts the transmission of Lyme disease. At the same time, the technology is actually a “platform” that can contain several vaccines and address multiple diseases.

The concept of oral immunization of wild animals to prevent human diseases is highly relevant to a number of other zoonotic diseases – those diseases transmitted from animals to humans. Zoonoses make up about 75% of emerging infectious diseases. Our technology provides an important example of the power of this approach.

Rick, what are the challenges going to be in terms of getting broad distribution for the mouse-targeted vaccine?

A key challenge will be getting the vaccine to the places where it will do the most good. The Lyme disease zone in the United States is enormous, and the white-footed mouse lives in pretty much all terrestrial habitats throughout this zone (including my kitchen cabinets). So, where do you deploy it, and how do you get it into the mouths of mice rather than having it get eaten by other animals? You can’t deploy it everywhere, so perhaps focusing on areas with the most cases of Lyme disease makes sense. If the vaccine is broadcast by air, much of it will likely be eaten by other wildlife, with little benefit in terms of reducing Lyme risk. If it’s placed in small boxes that only mice can enter, then delivery will be much more efficient, but this would seriously limit the area that can be covered. Because the mice have to ingest several doses to get immunized, making sure the bait lasts a long time will be critical. And the turnover in mice populations is extremely rapid, with new babies growing up and replacing the older generation constantly from spring through fall. So, one would have to deploy the bait for many months each year. Because our research showed that the reduction in tick infection takes a few years to materialize, one would have to keep up the delivery year after year.

What else beyond a mice vaccine does the Lyme prevention community need to do to prevent the spread of Lyme disease?

I agree that there’s much potential to consider the bait vaccine as a part of an integrated pest management approach. I think it’s likely that the bait vaccine together with tick management would act synergistically to reduce Lyme risk. Both tick-killing fungi and some botanical oils (oil of rosemary, for example) are known to be highly effective at killing ticks but without the toxic effects of chemical insecticides. By reducing the size of the tick population, one would not only directly decrease human risk, but also decrease the rate at which mice are infected. This would further reinforce the vaccine’s ability to reduce mouse-to-tick transmission. Recent research has shown that using insecticides on people’s yards does nothing to reduce their likelihood of getting Lyme disease. So, we have a lot of work to do to figure out where to deploy tick-control and bait vaccine strategies. Our nation spends far too little research money on these important questions, in my opinion.

For more information on this study: http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2014/02/11/infdis.jiu005.abstract

Photos are courtesy of US Biologic and Cary Institute

For more Ticks articles: click here

In The Global Search for Education, join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. Madhav Chavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. Eija Kauppinen (Finland), State Secretary Tapio Kosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Professor Ben Levin (Canada), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (Lycee Francais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today. The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland, and is the publisher of CMRubinWorld.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments