Trends Shaping Education 2016 is a new and updated OECD work which looks at major social, demographic, economic and technological trends affecting the future of education. The first edition of the book was published in 2008 and two subsequent editions were published in 2010 and 2013. The 2016 edition has been extended to include new countries and emerging economies including Brazil, China, India and the Russian Federation. The report covers all of education (early childhood through tertiary) and is intended for a broad audience including policy makers, educators, teachers, parents and students.

Author of the report and OECD Project Leader Tracey Burns joins us in The Global Search for Education

to discuss the big picture global changes and how they are shaping learning in our everyday world.

What are the greatest challenges we face in achieving the egalitarian ideals of education in a globalized setting that is becoming increasingly stratified?

The greatest challenge, in my mind, is rising inequality. In OECD countries, the gap between rich and poor is at its highest level in 30 years. Household debt has been rising, and youth are now at a greater risk of living in poverty than their older counterparts. This can lead to conflict and tension, particularly in diverse urban areas where the “other” (i.e. people from different racial and cultural backgrounds) becomes the target of discontent and the scapegoat for grievances. And new technologies are changing the game, for better or for worse. While they can and have been used to boost citizen engagement and empowerment (e.g, Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring), they also allow individuals and organisations to stay one step ahead of the law (e.g, terrorists using social media). There is a lot of pressure placed on education to act as one of the major levers to reduce inequality, but it cannot act alone.

What do you see as the respective roles of educators, parents, students, and citizens in overcoming this challenge?

Again, although education has a powerful role to play in reducing disadvantage, policies that determine the level of taxation, government transfers and the structure of labor markets all need to be changed hand in hand with education policy in order to significantly reduce inequality. That being said, educators can take the lead in a number of ways, such as providing quality early childhood education and care, one of the big levers in reducing disadvantage. Parents, students and citizens can promote civic engagement and become more involved in education governance, pushing the system to do more to reach out to those most marginalised. They can play a unique role in holding the system accountable to broader societal goals, in addition to education ones. And everyone can be more aware of the importance of physical and emotional well-being starting at the youngest ages.

What kinds of skills or competencies should we be teaching to meet shifting labor needs?

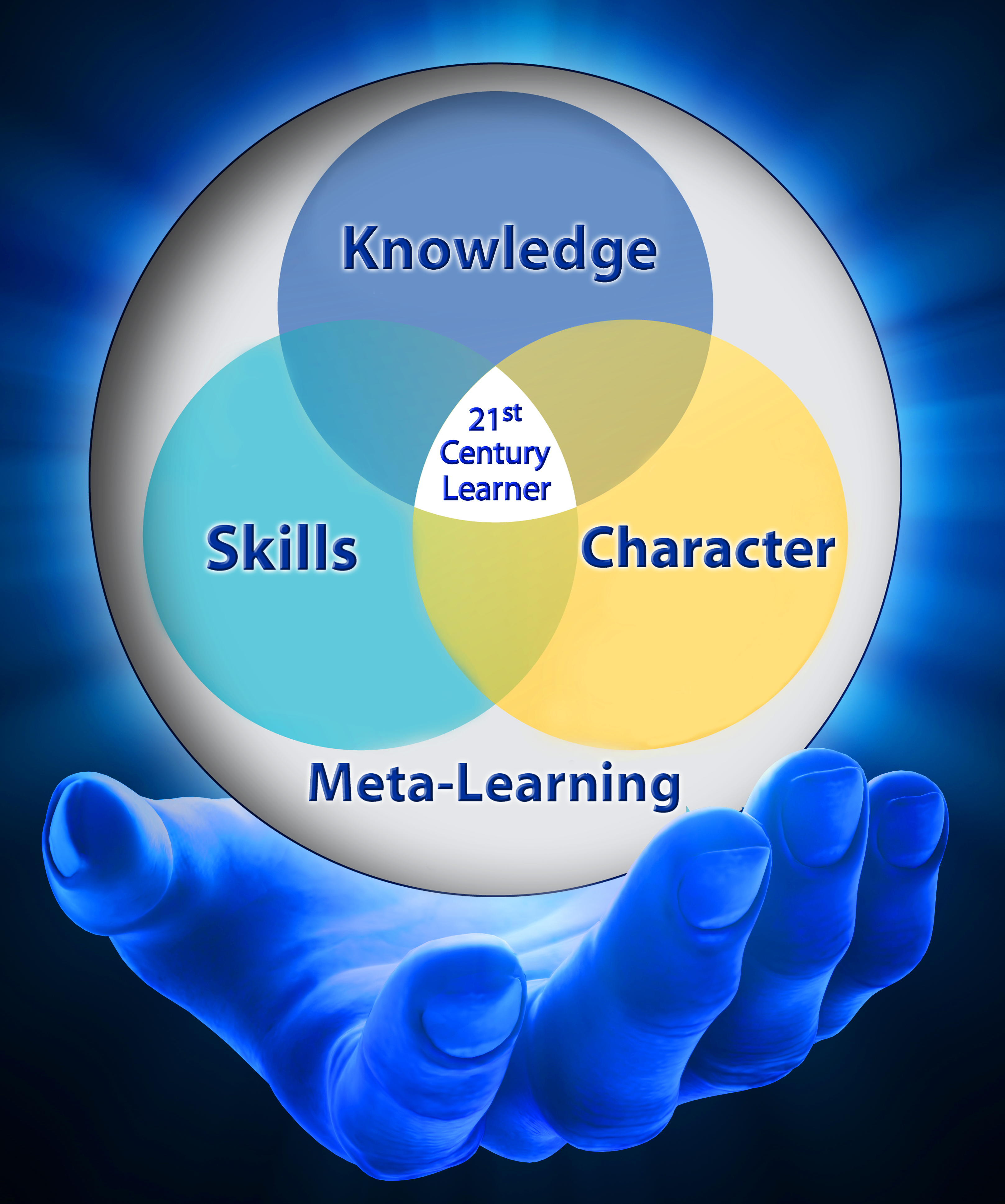

Educators need to be aware of the advanced skills their students will need to flourish in more knowledge-intensive labor markets, without neglecting the development of other important competencies. These include 21st century skills such as global languages, advanced digital skills, and social and emotional intelligence. Education can also play a role in helping equal the playing field for women, closing the gender gap in the workforce and encouraging female entrepreneurship. It will also increasingly need to continue to re-skill aging workers through lifelong learning, as our populations stay active for longer. For tertiary institutions, it is important to support R&D, attract and retain the best researchers, and reinforce studies that require high levels of knowledge and skill, creativity and innovation more generally. To this end, governments are also moving to streamline procedures required to start businesses, lightening the administrative load and incentivising entrepreneurship.

How can schools better prepare for the increasing numbers of immigrants from various cultures and socio-economic situations?

The most important step is to have a systemic vision. Across the OECD, students with an immigrant background tend to have less access to educational resources and their parents are less educated and work in lower-status occupations on average. Of course, there are a lot of individual stories within these averages that are quite different, but the systemic element remains important. Decisions about funding and resources, school autonomy and school choice, for example, must also pay attention to equity and access to educational opportunities. Certain system level policies, such as grade repetition and early tracking, amplify socio-economic inequalities within a country whereas others, such as the expansion of pre-primary education, can help mitigate them. Education can provide training and language skills as well as transmit norms that can facilitate immigrants’ integration into labour markets and their adopted country. It can also teach all students – not just the new arrivals – about the importance of tolerance and the benefits of cultural diversity.

What role do you see education playing in the rise of megacities? How can we address individual learning needs and teacher recruitment issues that arise from quickly growing urban areas?

Education can and should be prepared to adjust and grow along with urban environments. Education can teach civic literacy, provide the skills needed for community engagement, and support creativity and innovation throughout the lifespan. Designing liveable urban spaces and encouraging smart transport in increasingly dense cities will require urban planners and engineers, as well as the research and innovation hubs needed to fuel their work. The provision of proper support systems for at-risk students can reduce instances of bullying within schools and decrease urban crime by keeping kids in school and out of trouble. Education will also need to be prepared for a number of trends that arise from increasing urbanisation, such as planning for increasing (or declining) neighbourhood populations, and protecting school buildings and infrastructure from extreme climate events, expected to disproportionally affect large urban centres. Education will also continue to be responsible for ensuring the safety of students and monitoring physical and emotional well-being in the face of potentially new or growing urban stresses. However we must be vigilant: disadvantaged urban schools are more likely to lack qualified teaching staff. Attracting and retaining qualified teachers and principals in disadvantaged urban schools is key. Training programmes, mentoring, and on-going professional development all have a role to play.

A “green economy” may one day become less of an ideal than a necessity for the continued flourishing of our species. What can our educational systems do to foster the international co-operation required to devise a plan for coordinated action on global climate change, ecological disasters, and sustainable sources of energy?

Students must be taught the science and maths needed to understand the mechanisms underlying climate change. However this will not be enough: education systems need to create critical thinkers that are able to connect their daily decisions to long-term consequences – not just for themselves but for society as a whole. One way to do this is through engaging with complex, real world problems from very early on. Currently, students often spend time on highly structured tasks that do not leave much time for more creative activities where students can develop their critical thinking skills. In addition, the tertiary sector has a role to play in supporting green innovation, such as energy saving and environmental protection inventions, new energy technologies as well as low-carbon and resource-saving technologies helpful for green development.

As health and pension expenditures increase, national governments are expected to face increasingly tight budgets. How should we look to better finance education spending in the long-term?

On the surface, the more governments spend in areas such as healthcare and unemployment benefits, the less they have to support the education system. However, government policies in various sectors can play off one another in mutually beneficial ways. For example, greater military spending could help improve the quality of military academic programs, which could also enable more individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds to pursue their studies affordably. Alternatively, better education can reduce government spending in other areas. For example, teaching healthy habits in schools can play a role in reducing obesity rates and diabetes, lowering health care costs to governments and individuals. Similarly, improved life-long learning systems may be able to slow the development of dementia, one of the fastest growing causes of death in OECD countries. Finding these intra-governmental strategies is a good start to making the most of restricted public finances.

(Photos are courtesy of Shutterstock – Tania Kolinko, IOFoto and Bikerider London)

Join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. MadhavChavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. EijaKauppinen (Finland), State Secretary TapioKosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Geoff Masters (Australia), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (LyceeFrancais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today.

The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland, is the publisher of CMRubinWorld, and is a Disruptor Foundation Fellow.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments