Ebben a hónapban, a közönség képernyőzhet Saját Éned a Planet Classroom Networkön. Ezt a filmet a Planet Classroom a Planet Classroom Network számára készítette.

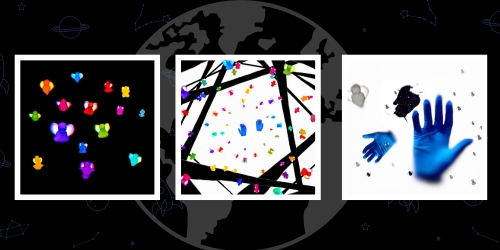

Saját Éned is a short dialogue-free animated film from writer/director Evan Bode. The film uses clay and hands as its storytelling tools. It portrays a group of colorful beings initially living harmoniously until they are forcefully molded into binary blue and pink forms by imposing surgical glove-clad hands. Saját Éned serves as a powerful allegory for society’s enforcement of strict gender roles, highlighting the violence and coercion involved in conforming to these norms. It was recognized as one of the winners in the 2022 Student Short Film Showcase, a collaborative award bestowed by The Gotham, JetBlue and Focus Features.

A Global Search for Education is pleased to welcome Evan Bode.

Evan, we love your short film—could you elaborate on the inspiration behind its unique concept of spirits rebelling against conformity to find their authentic selves?

As children, many of us go through an experience of being torn from a place of safety in expressing our authentic selves into a bright spotlight of cultural expectations and a social performance that may feel false. This socialization process can be damaging toward something inside that is very sacred—one’s own internal sense of identity and the freedom to express it. Kifejezetten, I am thinking about the gender binary and all the expectations that come with it, as an ideology imposed on us from the time we are born and even prior to birth. Since pink and blue are often used at gender reveal parties to signify one identity or another, the colors worked as a convenient visual shorthand to represent these ideas intuitively, without words. I was interested in exploring a power struggle against assumptions, labels, and systems of conformity imposed on our bodies, but I wanted to communicate these complex ideas in a way that is simple and accessible, almost like a children’s fable for any age.

As a person who identifies as genderqueer, I’ve always felt at odds with constructs of masculinity, in a way that’s difficult to articulate and express. This film comes from a personal place of trying to process and explore that through artistic means, in a way that can hopefully resonate with others and offer a message of hope through collective resistance to forces of oppression.

Your film employs a captivating blend of visuals and sound design. How did you approach balancing these elements to maintain a whimsical and magical atmosphere?

Általában, the score comes after the visuals when making a film, but since I was the one creating the music as well as the animation, I was able to work on them alongside each other in a closely integrated process, composing a little bit at a time along the way. With every shot, the visuals and music are in collaboration, and they developed that way from the start.

Sound holds so much power in determining the tone of any given moment in a film. This is especially true in Saját Éned, since the film contains no dialogue—the music is doing the speaking. This was my first time attempting to create music for a film, and although challenging, I found so much joy in the process. I think about music as a language of pure emotion, and it’s a very subjective language. Learning that language has been a practice of careful listening to my inner world, an openness to what I hear there, and an act of translating that to reach others. When I do discover a melody or musical progression that feels right to me, it’s an incredibly rewarding and exciting feeling.

Saját Éned explores themes of identity and liberation. What message or emotions do you hope audiences will take away from this story?

Growing up in a culture with a lot of emphasis on imposing two and only two social categories, we are trained to see traditional gender norms as something natural and inevitable, and to look down on any departure from these norms as unnatural. In this film, I’m trying to reverse that framework to say the opposite is true. The colorful diversity and fluidity of our identities is what is most natural and authentic, as much as the sky and trees. What is “unnatural” is this process of enforcing rigid boxes onto each other and policing those categories, which is a futile and dangerous effort, portrayed in the film through powerful disembodied hands making everyone dance to the same controlled dance of selfhood. The gender binary is not an objective reality, but rather a political notion that requires effort to uphold and police, or else it will collapse. We see this through constant efforts to oppress and restrict the rights of trans, nonbinary, gender-nonconforming, queer, and otherwise marginalized people.

Sajnos, diversity is threatening to some, but it is cherished by others. It has always existed and always will. Its continued existence, not its violent erasure, is what’s inevitable. It’s up to each of us to decide whether we want to embrace or reject what makes us unique, both in others and within ourselves. I hope the film nurtures a desire to live authentically and support others in doing the same, in an effort toward constructing a social reality in which we all have the freedom to live and breathe a little more easily as ourselves.

The use of stop-motion and mixed media is distinctive. Can you share any challenges or breakthrough moments you encountered while bringing this creative vision to life?

This film exists as the result of adapting to a limitation, which is that my first year of graduate film school took place online due to the pandemic. Emiatt, I gravitated toward animation as a form of one-person filmmaking that could be achieved from home in my parent’s basement without a production team. Every moment was both a challenge and a breakthrough, since the process was new and uncertain for me. This was my first time creating an animated film, and first time as a composer too, so I was teaching myself these skills as I went along and improvising with the limited resources I had to work with.

For the floating hands, I wore green sleeves under blue plastic gloves and filmed against a piece of green poster paper taped against a bookshelf, as a makeshift green screen. For the wings of flame, I filmed a green birthday candle against a plastic green plate. The branches are pictures of trees from my own backyard, and the army-like rows of gendered cubes are multiplied from a single clay figure. For the moment when my hands rip through the sky, I set my phone in the bottom of a trashcan, recording upward, and covered the top with black paper to tear through. All of these techniques were experiments in the spirit of independent, zero-budget filmmaking.

Through this five-month process, I found that I love the rough texture of a handcrafted look more than a style of smooth, polished technical perfection. The resulting distinctiveness preserves the artist’s personal touch, which is often erased when trying to conform to a standard aesthetic—an idea which connects back to the film’s themes. Constraints facilitate creativity, and what matters most is the idea you’re trying to express. I hope this inspires other young filmmakers to try new things and make the most out of what they have. In the words of the great experimental filmmaker, Maya Deren, in her ode to amateurs, “The most important part of your equipment is yourself: your mobile body, your imaginative mind, and your freedom to use both.”

Thank you Evan!

C.M. Rubin with Evan Bode

Ne hagyd ki Saját Éned, most a Planet Classroom Networkön közvetítjük. Ezt a filmet a Planet Classroom gondozta.

Legutóbbi hozzászólások