“For depressed rural areas, there are two options: Help people relocate to stronger areas or help them get skills and jobs where they are, at least partly through subsidized job creation and newer kinds of economic development.” — Harry Holzer

Donald Trump’s journey to become president of the US in 2016 raised high awareness of the employment concerns and challenges of America’s white working class. Even before the election, notes economist Harry Holzer, “less-educated Americans, particularly men with high school or less education, were stagnating or deteriorating.” Work activity among prime-age (25 to 54) men in America has declined harshly, leaving seven million or more working-age men in the US outside the labor force. The causes, says Holzer, include “lack of postsecondary education, dependence on benefit programs, opioid dependency, the rising prevalence of criminal records, a lack of available jobs in economically distressed areas, and weakening cultural norms.” Given the economic outlook and the technological upheaval that persists, how much further displacement can we expect to see in manufacturing industries? Will Artificial Intelligence also replace the analytical labor force? What are the biggest obstacles facing young graduates trying to enter the workforce now and in the future? Finally, will there even be enough jobs to go around ten or twenty years from now?

Harry Holzer is the John LaFarge Jr. SJ Professor of Public Policy at Georgetown University and an Institute Fellow at the American Institute for Research in Washington DC. He is a former Chief Economist for the U.S. Department of Labor and a former Professor of Economics at Michigan State University. His area of expertise is in getting people back to work using pragmatic policy solutions form both the left and right side of the political spectrum. The Global Search for Education is pleased to welcome him to discuss the workforce trends that should concern us all and to share perspectives on the sustainable solutions we need to pursue.

“The bottom tier of graduates – from lower-ranked schools and without good general skills that employers value (like communication and teamwork) and without specific task training that the labor market values does not always share in these strong labor market rewards.” — Harry Holzer

Harry, globalization and technological upheaval will continue to place immense pressure on current jobs and on the kinds of jobs that will be needed in the future. How severe do you believe jobsolescence will be over the next 20 years?

There is great uncertainty in my mind about how technology in the workforce will play out over the next 20 years. As you know, there have been many times in the past where people panicked over technology displacing workers, starting with the Luddites in the 19th Century. Their worst fears have never been realized. There was a technology scare in the US in the early 1960s. There was also a scare about offshoring to China and India about 15 years ago that also came to little.

The uncertainty exists because we don’t know how technology will be embodied in capital goods and also in consumer goods, and at what prices, especially relative to those of other forms of capital and labor, and how these other forms of capital and labor will adapt. Just because a form of technology exists, and is theoretically capable of being implemented, it doesn’t mean that it will do so at large scale.

Having said that, technology does displace some workers, whose long-term earnings are reduced, and it has reduced demand for unskilled workers in the US more broadly. To date, it has mostly affected workers who perform routine tasks – like those in production and clerical jobs.

“The barriers to creating more good pathways to the middle class include the low resources, weak incentives, and multiple expectations that we have for community colleges.” — Harry Holzer

We are just at the beginning of AI. Looking forward, what are the critical skills we should focus on to ensure humans protect themselves from jobsolescence?

I suspect the potential impact of machines with AI will rise, and will affect any jobs where data analysis is part of the work. That could well affect jobs in medicine, accounting, financial and legal services. But practitioners in these fields could retain their work if they increasingly focus on the parts of the job that machines cannot do – such as interacting with customers in a human way – and become complements to the machines rather than substitutes.

I think there is an interesting tension between specific and general skill formation in the labor market today, especially for those earning post-secondary credentials short of a BA. On the one hand, in a highly uncertain future, broad skill formation offers the best protection against displacement, especially in the skills that machines will not do anytime soon. On the other hand, when training disadvantaged students, the best results occur from training them in specific high-demand fields today, like health care, advanced manufacturing, IT, transportation/logistics, etc. Sector-based training and apprenticeships work well for such students, even though they are quite specific to particular industries or firms. So I favor continuing to train sub-BA students in these manners (or even the lower tiers of BA students), while still giving them a broad enough range of skills that they can hopefully retrain if their jobs become obsolete in the future.

What do you think are the biggest obstacles facing college grads today trying to enter the workforce?

Young college grads today were heavily affected by the Great Recession, but they are recovering as the labor market tightens. On average, they still do vastly better in the labor market than those without degrees. But the bottom tier of graduates – from lower-ranked schools and without good general skills that employers value (like communication and teamwork) and without specific task training that the labor market values – does not always share in these strong labor market rewards.

“The strong workforce and occupational programs are often limited in size and capacity. Students are also poorly informed and get very little guidance and support. They mostly think they will transfer and get BAs, but few do.” — Harry Holzer

There are increasing anxieties about pathways to the middle class. What are the major obstacles to creating new pathways to the middle class in America? How important is the role of education, both access to information and skill training, in this endeavor?

The barriers to creating more good pathways to the middle class include the low resources, weak incentives, and multiple expectations that we have for community colleges. So the strong workforce and occupational programs are often limited in size and capacity. Students are also poorly informed and get very little guidance and support. They mostly think they will transfer and get BAs, but few do. In addition, CTE programs in high school have a long tradition of being low-quality and tracking kids away from college, so it is hard to improve their quality.

High school graduate workers who reside in rural areas or small- to medium-size metro areas have suffered substantial job loss in the past few decades, especially in manufacturing. How do we fix this problem?

For depressed rural areas, there are two options: Help people relocate to stronger areas or help them get skills and jobs where they are, at least partly through subsidized job creation and newer kinds of economic development. The latter is challenging but not impossible. But if they have opioid dependencies or are on disability insurance, or have criminal records or unmet child support obligations, these will have to be addressed as well.

Thanks Harry

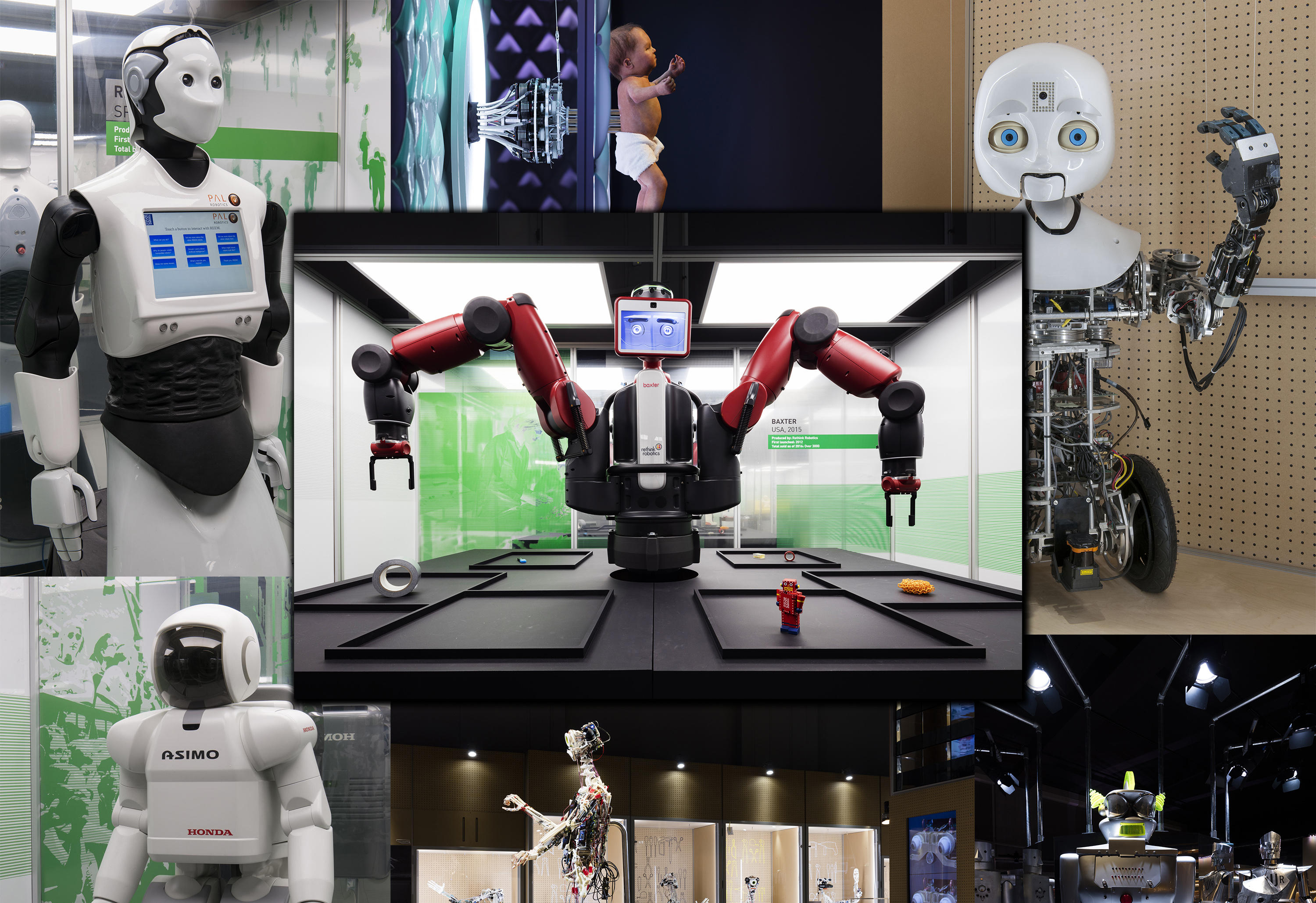

(All Pictures are Courtesy of CMRubinWorld)

Join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. MadhavChavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. EijaKauppinen (Finland), State Secretary TapioKosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Geoff Masters (Australia), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (LyceeFrancais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today.

The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland, is the publisher of CMRubinWorld, and is a Disruptor Foundation Fellow.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments