Tap Screen to Start!

Project: EVO is a mobile game platform that trains your brain to ignore distractions and stay focused. Pilot study results reveal that the game improved attention and working memory in pediatric Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). It’s not the first time that research has recognized that playing video games can have a positive impact on student development.

Tilt the Device Left and Right to Steer!

But does this mean that educators and parents addressing the challenges of educating children with ADHD, many who saw digital toys as kids stuck in front of a screen damaging their already fragile abilities to focus, will soon be steering their charges to more game play?

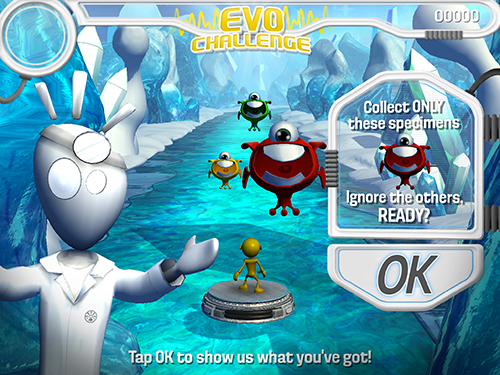

Here Are Your Target Specimens!

Could an action-packed, graphically enticing racing game (if approved for treating pediatric ADHD) actually present a viable new option to ADHD drugs one day? Sounds pretty awesome to me!

Just how well did you multi-task during your homework assignment?

Helping students develop the skills to focus is something educators and parents recognize as critical to driving better learning outcomes. With me today in The Global Search for Education to talk about Project: EVO is Eddie Martucci, co-founder and CEO of Akili.

Eddie – What brain functions does the Akili system focus on? How does this compare to other approaches?

Project: EVO is built to measure and affect a key neural process known as “interference filtering.” Unlike technologies that are designed to address top-level cognitive domains like attention or working memory or executive function or planning, our technology targets the more basic ability of an individual to perceive and prioritize conflicting streams of information (or “interference”) which should allow an individual to control his or her goals in sensory rich environments, like everyday life. Proper processing of sensory inputs is important for all of these top-level cognitive functions, so may be an efficient way to both measure and intervene in a very targeted way.

How does the EVO gaming mechanism and game play address the deficiencies that are identified?

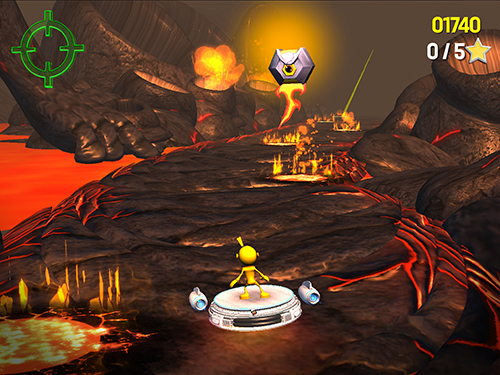

Based on research and inventions we licensed from Dr. Adam Gazzaley at UCSF, the technology requires a user to constantly manage two competing streams of high-resolution motor (driving a character/vehicle) and visual (making split-second decisions on objects that appear in the environment) information. These are coded into an action gaming environment with patents pending both for the way in which the streams of information are displayed to the user and the Akili-developed adaptive algorithms to make the difficulty constantly tuned to the user so the entire experience is automatically personalized.

Since this interference-rich environment is constantly pushing a patient to better manage his/her incoming information, the hypothesis is that this should allow an individual to better manage attention, short-term memory, impulsivity, and a number of other domains that depend upon cognitive control. The early data from our open-label pediatric ADHD study indicates that indeed we see positive improvements in tests and parent reports of attention, working memory, and impulsivity, which are all domains where ADHD children and other populations show specific weaknesses.

What adjustments in gameplay does EVO make to match the patient’s ability level? Does it also adjust to the degree of mental deficiency of the patient?

Project: EVO assesses a patient’s level upon initial use and then continuously and remotely monitors performance real-time. We think it’s important to make sure the software can adapt to handle a wide array of types of patients. During use, the game adapts in three main ways:

- Second-by-second, both the motor and perceptual demands (speed and sensitivity) adapt in difficulty;

- As the patient masters certain tasks, new rules (levels) are introduced where complexity of the tasks increases (for example, more rules and decisions to make);

- Rewards are continually re-set by the patient’s performance, so that each person can progress in a personalized manner.

In plain English, what level of measurable effects have you found in participants using EVO?

The pilot study included 40 children between 8 and 12 years of age who were diagnosed with ADHD and not on medication. Using standard cognitive tests, we measured attention, impulsivity and working memory before and after one month of at-home interaction with the device, and found statistically significant improvements in these 3 areas, and especially large improvements for children with substantially higher attention impairment at the beginning of the study. We also saw statistically-significant improvements for this later group in parent-reported working memory and inhibition (ability to control impulses).

What questions do you plan to address in further testing of EVO?

We plan to initiate a large, randomized, controlled pivotal study in the coming months, which is aimed at definitively showing the benefits of our intervention for children with ADHD. The intent is to use it for submission to the FDA for approval. It’s very interesting to us that many patient populations (from psychiatric conditions like depression to other populations like traumatic brain injury and neurogeneration) show issues in similar domains dependent on this cognitive control, so we’re exploring the potential of the technology in various populations to see where we have the most impact on patients. At the end of the day, we want to make products that are in markets where there are clear patient needs that aren’t being addressed well with current options.

(All photos are courtesy of Project: EVO, Akili Interactive Labs)

Join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. MadhavChavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. EijaKauppinen (Finland), State Secretary TapioKosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Geoff Masters (Australia), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (LyceeFrancais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today.

The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland, is the publisher of CMRubinWorld, and is a Disruptor Foundation Fellow.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments