Our world is getting increasingly complex; so how do we know what is worth teaching and learning? I watched David Perkins’ presentation on this timely topic at the IB Heads World Conference this year and I am delighted to welcome him today to The Global Search for Education. David is interested in how we ought to adapt our curriculums in light of an ever-changing world. He asserts that what is conventionally taught in our schools is not necessarily meant to produce the kinds of community members we want and need. Perkins believes that only by reimagining what we teach our children can we lead students down the road to learning that results in a flourishing life.

David Perkins is the Carl H. Pforzheimer, Jr. Research Professor of Teaching and Learning at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and a founding member of the Harvard Project Zero, a research project investigating human symbolic capacities and their development. He has participated in curriculum projects addressing thinking, understanding and learning in Colombia, Israel, Venezuela, South Africa, Sweden, Holland, Australia and the United States. David’s latest book, Future Wise: Educating Our Children for a Changing World, is a toolkit for helping educators and parents think through the all-important question: “What’s really worth learning?”

What do you think students need to be taught in order to prepare them for life?

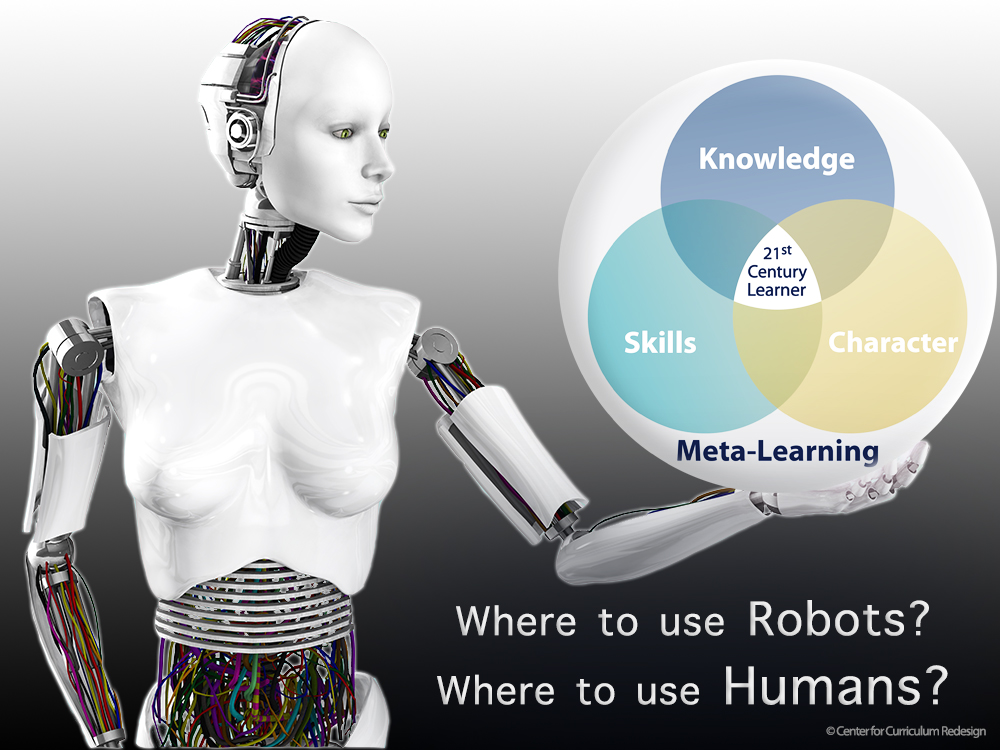

This is perhaps the most important question in education for today’s complex world! Let me respond not by declaring a curriculum but exploring how we ought to think about it. From teachers to school leaders to makers of national policy, we should be asking, “What topics are truly likely to matter in the lives today’s students will live?”

For any candidate topic, I encourage people to tell an “opportunity story.” How might this topic come up later in students’ lives? With what frequency, what importance, offering what insights, empowering what actions in the world, informing the ethics of their decisions and the policies they support? Traditional curricula are stuffed with topics that resist a good opportunity story, topics just “there because they are there.”

What are examples of “big understandings,” as I call topics with a strong opportunity story? For instance, understanding democracy not just as an ideal but in its complexities and shortcomings around the world; or energy – its physics, economics, politics. Or basic statistics and probability… which come up frequently in medical decisions, insurance decisions, gambling, policies that impact the poor or international conflict. Also, many powerful works of art, literature, and music that resonate with the human condition.

What steps should schools take to ensure they are constructing a curriculum which prepares their students for the future?

What’s needed here is a rich conversation within and across schools, including school boards, parents, and even students. Much of that conversation involves sketching and critiquing opportunity stories. It’s hard to tell a sound opportunity story solo. One needs the rich critical conversation!

How should schools identify the key aspects of the curriculum they need to focus on in the classroom to ensure that students develop the key competencies they need in life?

One place to look is the traditional disciplines – mathematics, history, etc. I grumbled earlier about the clutter of limited topics, but any discipline also contains abundant “big understandings.”

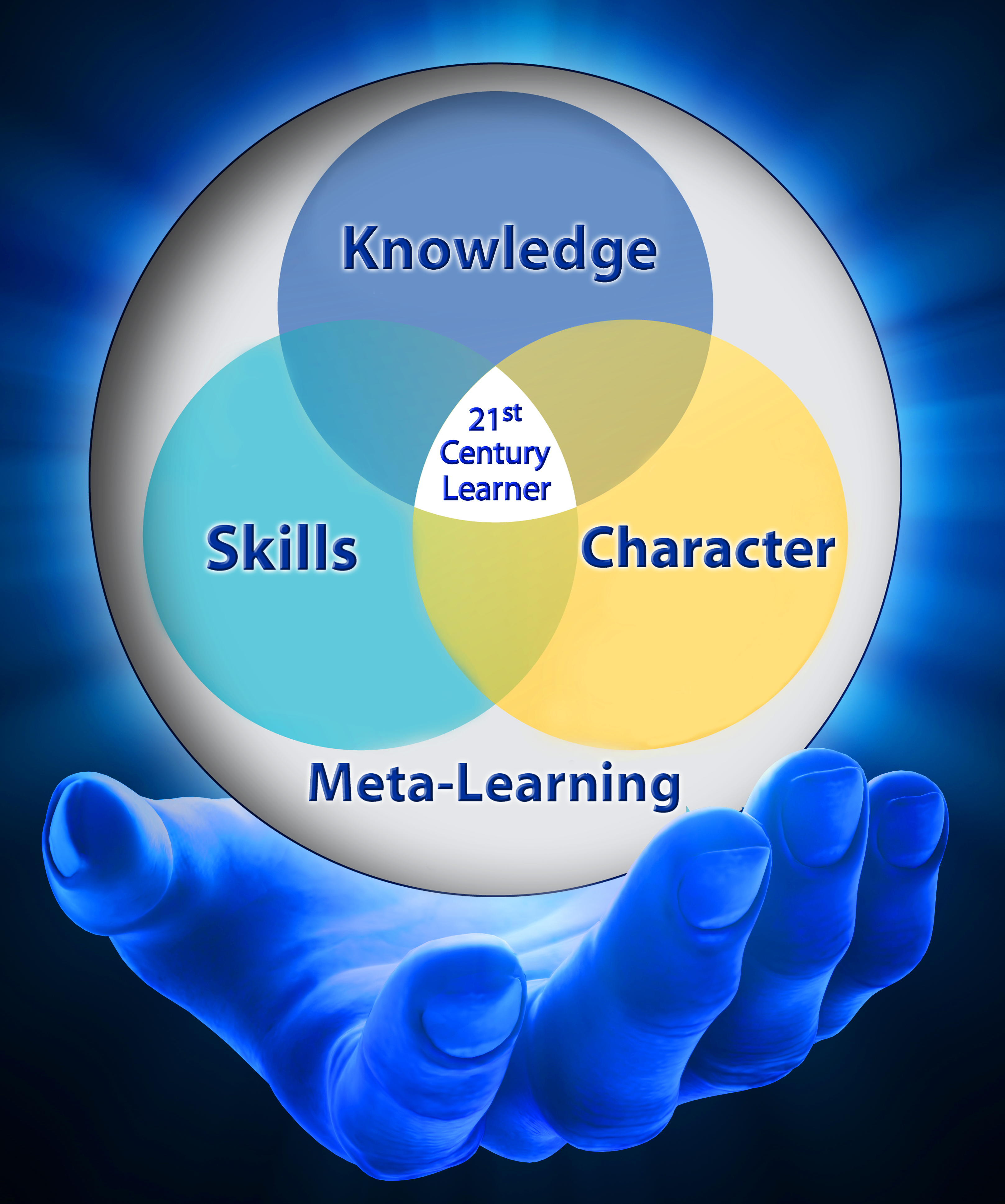

Another place to look is outside those disciplines. Based on comparative study of curriculum innovations, I can point out six “beyonds,” where educators are venturing beyond the traditional disciplines, in brief: beyond content, infusing 21st century skills, competences, etc.; beyond local, embracing global perspectives, problems, and studies; beyond topics, transforming topics into tools of broad understanding; beyond the traditional disciplines, renewing and extending those disciplines; beyond discrete disciplines, embracing interdisciplinary topics and problems; beyond academic engagement, fostering personal significance, commitment, and passion.

You stressed that many topics can be rich with learning opportunity – much depends on how teachers help students to develop insight about how some aspect of the world works, see potential for action, ponder ethical issues and generally see opportunities to build relevant links to their worlds. You state that topics that don’t have this potential should be removed from the curriculum. Based on your research, what are the top 5 strategies you would recommend to teachers to help them with this?

What to do with topics lacking a good opportunity story is a tough problem for educators. It’s always harder to take something out than put something in. Here are some suggestions for how to do it.

- Don’t take the topic out. Shrink it! Make it an object of “acquaintance knowledge” so that students have some orientation to it.

- Don’t take the topic out. Expand it! Many topics are thin only because they are thinly treated, but one can greatly increase their reach by looking for big generalizations and making connections to other areas. For instance, don’t just teach the French Revolution as about the French Revolution – teach it quite explicitly as a source of big themes that touch many other revolutions and various social innovations not only in the past but today. And pursue those connections as part of the instruction!

- Don’t start by planning what to remove but what big understandings to get in. With a positive agenda defined, it’s much easier to decide what to.

- Don’t start by redesigning your whole curriculum. Start with a manageable unit or two. Make the entire transformation a project of two or three years.

- With all that said, of course sometimes just take the weak topic out!

Based on your research, what top 5 strategies would you recommend to teachers to help them nurture the 4 C’s (creativity, critical thinking, communication, collaboration) in classrooms?

First, let me note that there are many frameworks offering versions of 21st century skills. The 4 C’s is just one and not the only reasonable choice. However, I do think it’s quite a good one – broad enough to touch on important learner needs, compact enough to be manageable.

I’d encourage teachers to address the 4 C’s (or in fact almost any 21st century skills framework) as follows:

- Approach the C’s through “infusion,” weaving them into the teaching and learning of content.

- Be explicit about strategies. Research shows that students learn such skills better through making good practices explicit rather than just exercising them tacitly.

- Take a dispositional approach. Don’t just foster the skill’s development but also enthusiasm, commitment, sensitivity to occasions. Make such expectations part of the classroom culture.

- Teach for transfer. Declare an expectation for transfer, invite students to consider where else the C’s might apply within and beyond school, ask students to log stories of application.

- Coordinate across the subject matters. Use the same C approach in multiple subject matters yourself or by coordinating with teachers who teach the other subject matters. This reinforces the C and fosters transfer.

Thank you for your questions. I’m much more hopeful today than I was 20 years ago that we will see some fundamental changes in education. And I’m delighted to be part of the dialogue.

Our thanks to you David!

(All Photos are courtesy of Light Poet and Bike Rider London, Shutterstock.com)

Join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. MadhavChavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. EijaKauppinen (Finland), State Secretary TapioKosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Geoff Masters (Australia), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor Pasi Sahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (LyceeFrancais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today.

The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, “The Global Search for Education” and “How Will We Read?” She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland, is the publisher of CMRubinWorld, and is a Disruptor Foundation Fellow.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments