“It was incredible to see women engage with the subject of honor killing very vocally online at the time of her murder, to see that they felt they could not stay silent, to talk about how a Pakistani woman can and should behave and what happens when she is believed to misbehave.” – Sanam Maher

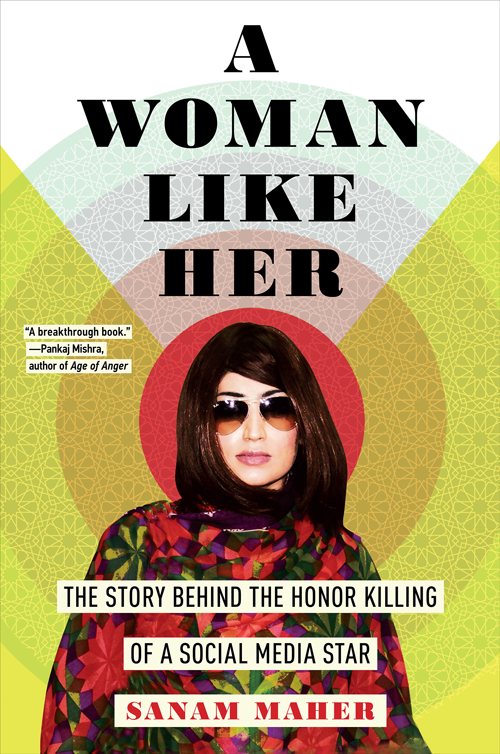

Sanam Maher is a journalist based in Karachi, Pakistan. A Woman Like Her: The Story Behind the Honor Killing of a Social Media Star is her first book. It tells the story of Pakistan’s first social media celebrity, Qandeel Baloch, who was murdered in 2016 at age 26 in a suspected honor killing. Baloch’s murder quickly became a media sensation. It was a story Maher felt compelled to tell. She remembers the moment the death of Baloch hit social media where people were having arguments about whether what had happened to Baloch was right or wrong. She watched friends and family members draw a line and very firmly position themselves on either side. It was in her words, a defining moment for Pakistanis, “what we hope for or believe we deserve.” Maher wanted to tell a story about “what it means to be a woman living in Pakistan today.”

The Global Search for Education welcomed Sanam Maher.

“With Qandeel’s murder, many women were coming forward to say they were fed up with shouldering that burden.” – Sanam Maher

Why is Qandeel Baloch’s honor killing so significant in Pakistani culture today?

It would be a challenge for the average Pakistani to recognize the faces of any of the hundreds of men and women killed for honor every year. Sometimes we don’t even read the stories about honor crimes buried in the third or fourth page of the newspaper. But Qandeel was different. There was a sense of having known her as many of us engaged with her frequently online, whether that was to bait her, shame her, secretly watch her videos at night, or share her videos with friends, imitate her and make a meme of her. It was incredible to see women engage with the subject of honor killing very vocally online at the time of her murder, to see that they felt they could not stay silent, to talk about how a Pakistani woman can and should behave and what happens when she is believed to misbehave.

What did you learn from the village where Qandeel grew up?

I travelled to the village in southern Punjab where she was born and raised. In one interview, a man told me about some of the men in his community. “They do not give their women shoes,” he said. I was confused about what he meant. He explained, “Imagine you do not have shoes on your feet and you step out of the house. Where will your eyes remain? On the ground. You will never look up – never look at any man – or look around you. You will only look down.” Those interviews and being in that place completely changed the way I wanted to work on the book.

“Social media was both a conduit and a threat for Qandeel.” – Sanam Maher

Talk a little about the global #Metoo movement and the timing of your book?

Pakistan is notably obsessed with its ‘image’, and the question of who is good enough to represent the nation or what face we should show the world has dogged us for decades. We’re seeing that manifest itself right now as women add their voices to the #MeToo movement, only to have their detractors accuse them of trying to “shame” Pakistan or “bring a bad name” to the country. Pakistani women seem to bear the weight of expectations when it comes to determining how we would like the world to view us. With Qandeel’s murder, many women were coming forward to say they were fed up with shouldering that burden.

There’s a new young generation of Pakistanis digitally connected to each other and their international peers like never before. What does Qandeel’s story teach us?

Social media was both a conduit and a threat for Qandeel. So when I was looking at her fame as a viral star, I began to think about how my generation of Pakistanis has been connected to the world like never before – what are we doing online? What does it mean to go viral in Pakistan as she did? What happens when we behave in a way online that seems to break the rules of how we are supposed to behave, particularly as women, “in the real world”? I wanted to explore how we might be connected to a global space of ideas and possibilities online, but we’re still very much grounded in the society and culture we live in here in Pakistan. Through Qandeel’s story and some of the others in the book, you see the terrible ramifications that a clash between the two can have. Something important that Qandeel’s story shows us about the ways in which we engage with social media is the constant trickle of information from online spaces into the greater public sphere. Conversations and movements online are discussed on talk shows and in the news, so even if you aren’t on social media, you’re probably still going to receive information being spread there. What effect does that have and what role did that play in Qandeel’s murder?

“Qandeel created a blueprint for how viral fame could be leveraged into a lucrative career, and she could do that because she knew how to create a persona that she knew would appeal to us.” – Sanam Maher

Did you receive any backlash during the book publication process?

In Pakistan, we don’t have very many independent bookshops and without a platform like Amazon, you’re dependent on larger bookshop chains to make sure your book sells. At one, I was told that they didn’t want to give me space to do any book events, and if I hadn’t put Qandeel’s name in the book’s title or put her face on the book cover, they might have reconsidered. The book came out during Ramadan, and for many, that was excuse enough to say they didn’t want to publicize the book. This is funny considering that the book sold out within that month in Pakistan, but evidently booksellers thought that there was no way they could have anything to do with “a woman like Qandeel” during the holy month of fasting. Readers messaged me on social media to tell me that at one big bookshop in the capital, they kept my book behind the counter and only handed it over to customers who requested it – almost as if it were pornography! While I largely had a fantastic response from readers on social media, I do hear from people who tell me that I’m just as shameless as Qandeel because I’ve “wasted” my time writing about her, or that I’m “clearly an atheist” because no self-respecting Muslim would work on a book about Qandeel.

Why is Qandeel’s story so important to you?

Qandeel created a blueprint for how viral fame could be leveraged into a lucrative career, and she could do that because she knew how to create a persona that she knew would appeal to us. What did we see that reflected back to ourselves when we watched her videos or looked at her photographs? That’s a question I wanted to answer when I wrote about her.

In one interview shortly before her death, Qandeel responded to a caller who asked why she didn’t do “something good” with her popularity. “I would like to,” she said, “but there are a lot of issues in my life right now. I am in the middle of dealing with not one, not two, but three cases filed against me, I’m dealing with controversies, and then, my brothers want to kill me.”

Three words that describe your book?

Nuanced. Shameless. Feminist.

C. M. Rubin and Sanam Maher

Thank you to our 800 plus global contributors, teachers, entrepreneurs, researchers, business leaders, students and thought leaders from every domain for sharing your perspectives on the future of learning with The Global Search for Education each month.

C. M. Rubin (Cathy) is the Founder of CMRubinWorld, an online publishing company focused on the future of global learning, and the co-founder of Planet Classroom. She is the author of three best-selling books and two widely read online series.Rubin received 3 Upton Sinclair Awards for “The Global Search for Education.” The series, which advocates for Youth, was launched in 2010 and brings together distinguished thought leaders from around the world to explore the key education issues faced by nations.

Follow C. M. Rubin on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@cmrubinworld

Recent Comments